I can trace it back to 1997, in a suburban Florida movie theater. My belief that having a suitor draw your portrait was the most romantic and truest demonstration of admiration and devotion any girl could hope for started there, with Rose and Jack in the throes of passion on a soon-to-sink Titanic.

This week at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that fantasy died, hard. I blame Cézanne.

"Madame Cézanne," on display through March 2015, is a 24-painting lesson that the artist-model relationship is not inherently steamy or fun. Cézanne met Hortense Fiquet at a Paris art school, where she worked as a part-time model. Concerned that his father, a wealthy banker, would not approve of their relationship, Cézanne kept their love secret . . . even after the pair had a son.

By the time they got married, Cézanne is on record saying that his interest in Hortense had fizzled. Despite the fact that they spent much of their marriage living in separate homes, and that he cut her out of his will, Cézanne painted portraits of his wife for over 20 years. Needless to say, these paintings do not overflow with desire. Relationships are complicated, though, and it's refreshing and comforting to see an entire exhibit that stands knee-deep in the mud of marital mediocrity and remains captivating, with nary a rapturous nude in sight.

Lest it seem that Hortense (or Cézanne) just picked some bad numbers in the art-spouse lottery, it's worth considering some other prolific pairs whose partnership was less than picture-perfect. Pierre Bonnard became practically hermetic in doting on his ill and reclusive wife, Marthe, who he painted 384 times. Though he often painted her nude and always with a veneer of youth, even as she aged, Marthe was part muse, part warden: Bonnard had to feign walking the dog to get out of the house to see friends. Picasso's wives and lovers appeared frequently in his work, and you can consequently watch his regard for a woman deteriorate from the flush of love to "it's not you, it's me . . . and my new girlfriend " in museums across the globe.

Art at its best reminds us that people from pre-history to the 20th century lived lives just as messy, and full of breaking up, making up and awkwardness, as ours. Perhaps we can learn from Hortense that it's easier to show your best side on a sinking ship than in a bad relationship.

The paintings, and Cézanne’s descendants, suggest that the aloof and unforgiving Marie-Hortense was not without fault in the demise of the union.

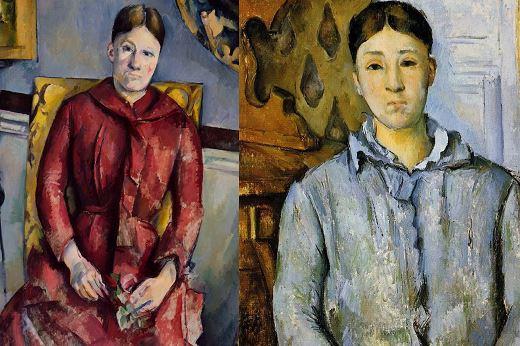

Portrait of Madame Cézanne in a Striped Dress (1883–85). Yokohama Museum of Art, Japan.

Undeniably, something drew Cézanne back to his familiar subject again and again—it could be love, appreciation of her bone structure, or ease of access. He also painted a lot of apples, and many of those come off as friendlier bedfellows than Hortense.

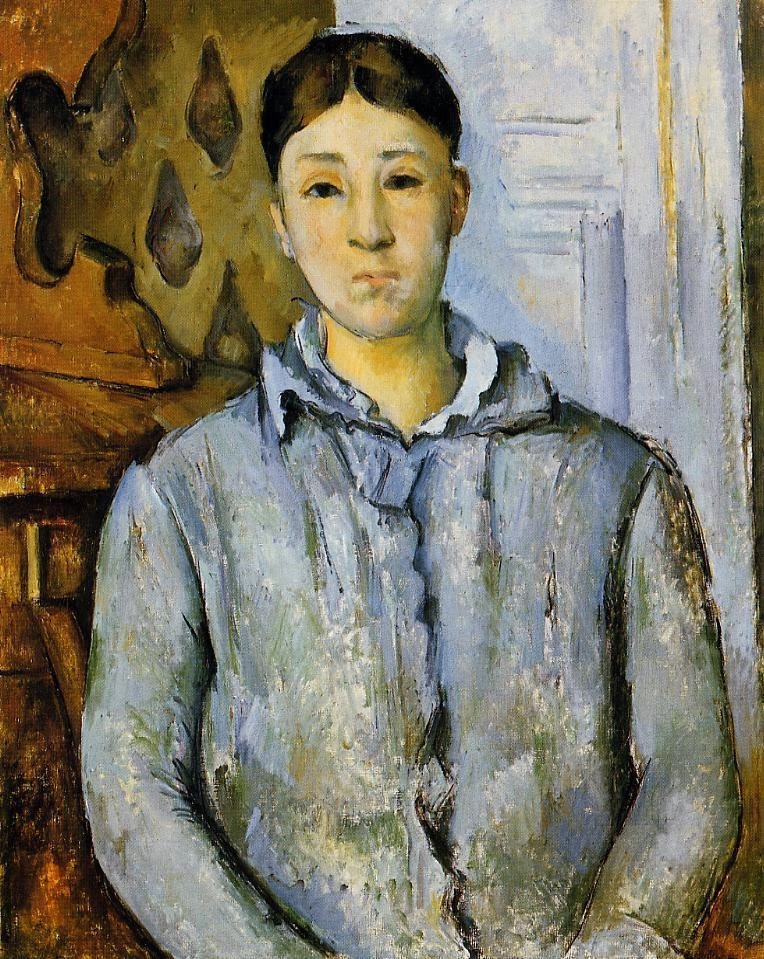

Madame Cézanne in Blue (ca. 1888–90). Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Art historians and Cézanne biographers have been unsympathetic to Hortense, deriding her as talkative, stupid and addicted to seedy romance novels. One of Cézanne's friends, art critic Paul Alexis, nicknamed her "the ball." However, Cézanne himself has also been called a cranky, complicated loner.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (ca. 1877). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

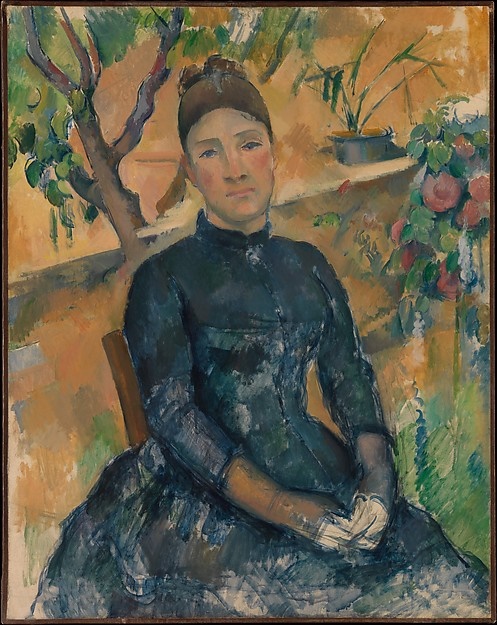

While the paintings may fail to elicit much empathy or warmth for their subject, Cézanne's skillful and dynamic use of color and pattern is on full display here, and they remain a joy to look at.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1888–90). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hortense's face, dress and surroundings never look quite the same twice, suggesting that Cézanne used these paintings not just to show us how he felt about his partner, but to explore the variety of pictorial potentials contained in a single subject.

Madame Cézanne in the Conservatory (1891). Metropolitan Museum of Art.