Photo of sunset in Madagascar courtesy of the author.

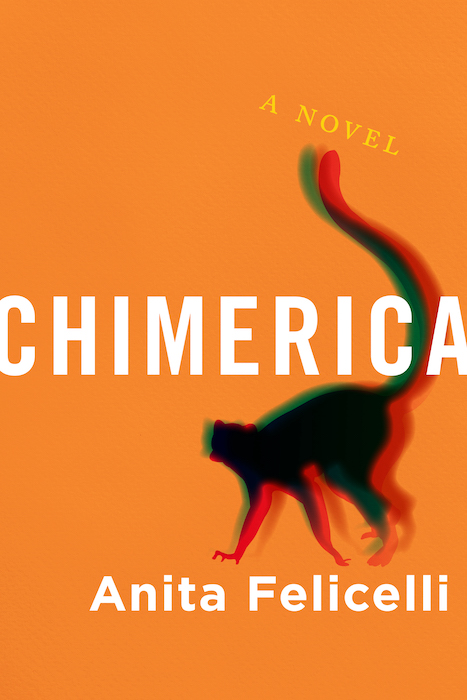

A little etymology is necessary before describing Chimerica, Anita Felicelli’s debut novel aptly characterized by Jonathan Lethem as “a coolly surrealist legal thriller.” Chimera can denote a monster, a fantasy, or an organism containing at least two distinct sets of DNA. It is this hybridity, multiple sets of DNA woven together to form something new, that sets Chimerica apart.

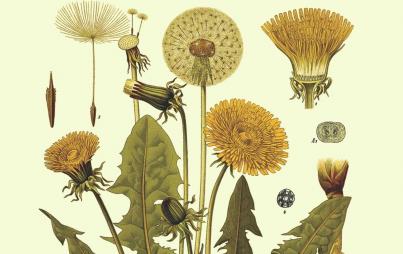

The novel opens when Maya Ramesh, an ambitious young Tamil-American lawyer, learns she has been let go from her law firm, jettisoned amid a complex trial where she’d represented a celebrated muralist suing the owners of a grocery store for having painted over one of his early works, a large-scale depiction of the indri, or large lemurs native to Madagascar. Spencer, the senior partner who dismisses Maya, tells her she lacks toughness and does not have the right temperament to win a big trial. With her husband having recently decamped to an apartment with their two children, Maya finds herself alone and now unemployed, but filled with a gambler’s angry faith that she can, and should, win it all back.

Then things get weird. A four-foot-tall lemur appears on Maya’s back deck and says in perfect deadpan, “Took you long enough to notice my existence.” The lemur explains that he has climbed down off the mural and wishes to be taken to Madagascar, where he belongs. But Maya seizes upon the opportunity to use the animal to insinuate herself back into the trial and her old job. What follows is a blow-by-blow legal thriller that pits creation against creator, art against law, existence against personhood, alien against national.

I spoke with Felicelli over email about artistic endeavor, ownership, and the intersection of law and art. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Would you characterize Chimerica as magical realist or surrealist? Did you always know it would contain fantastical elements, or did that evolve in order to tell the story in the right way?

I characterize it as surrealist. The world of the novel is askew in well-defined ways, but there isn’t an abundance of magical occurrences in the text. I always knew it would be surrealist because that’s how I perceive the real world, and it’s more of a struggle for me to keep myself in what is recognized as realism in my fiction.

How did you choose the title?

A “chimera” is an illusion. I was questioning whether the American dream was worth the sacrifices immigrants of color make to achieve what in so many ways is an illusion, only to see their children never treated as fellow Americans. I also wanted to interrogate the story America tells about itself and immigrants of color by thinking about the chimera as a mythological beast made up of very different animals.

As an outsider in terms of her identity, Maya’s always had to pay attention to what stories resonate with which people in order to assimilate. I grew up in a Tamil family that was intent on assimilating, but within our house, we maintained Tamil culture. My two best friends were Chinese-American, and I came to see differences in their home lives versus our shared school lives, too. I experienced a realization that some of us needed to become fluent in different languages to connect with different people, to make lives for ourselves in a strange land.

The novel is very concerned with how the public feels ownership over people and stories. The media has recently revisited the narratives of certain maligned women—Monica Lewinsky, for example. Do you think the public is becoming more sensitive to narratives being hijacked by the media, and more willing to see multiple sides of a story?

I hope so! But I’m not sure. I remember being horrified at the treatment of Monica Lewinsky. But over the next few years, observing women attorneys in law firms, I saw that women don’t become sainted because they’re mistreated and discriminated against; they become what is known as “difficult.” However, you would never survive as a woman in litigation if you weren’t “difficult.” It’s a double-bind. Women in law or politics constantly have to make compromises with their ideals; it’s how you get things done with the other side. I don’t know if the public or the media understands that yet in a deep way, and part of what I was trying to do in dramatizing Maya’s ambition in Chimerica was to take a look at what that inequality does to someone’s psyche. Maya’s told by her boss she isn’t tough enough, but how much of that is racism and sexism? She’s fired for reasons that are never revealed. I wanted to suggest that she’s been maligned and underestimated by her firm because of her identity. Her biggest stumbling block is internalizing this criticism, of focusing on proving herself to her critics, instead of doing what’s right.

At one point, the lemur says, “Anything that’s different loses its agency, gets exploited and funneled into the consumer economy.” Does this refer to this same notion of being held captive to public opinion? If everything gets squeezed through the funnel of consumerism, what does that mean for the future of creative endeavor?

Yes, the lemur is saying that whatever deviates from the ordinary and status quo — and this is intended to be taken in the broadest possible sense — is exploited for its commercial value, for what the public can extract from it. I'm pessimistic about capitalism, but I'm not pessimistic about creativity. However, many creative endeavors are dependent on drumming up majority support for the work, and this will always require an artist's adherence to existing forms and genres—something only a little bit different, rather than what's wildly original. I tried to play with this in how I sketched the lemur; he catches the public's attention in the novel because there's something familiar about him, but simultaneously, he unsettles because he's a little strange and different.

Mark Rothko said, “A painting is not a picture of an experience; it is an experience.” I imagine if Mona Lisa climbed down off the wall and ran away, her absence would likely ruin both the painting and the experience of the painting. How much value is there in a painting versus the experience of the painting?

Yes, if Mona Lisa ran away, it would cause a great commotion. We, as individual readers may be rooting for the lemur, but the lemur's public is deeply divided in the novel. They care about the lemur because of the artist's celebrity, and because of the way public art becomes a part of them. But I believe the value of a painting itself is arbitrary and set by society. It’s related only roughly to something inherent in the painting but also determined by external factors like the extent to which it deviates from what’s already present, the artist's identity, where it appears (a museum or gallery or the street), that amorphous concept of what coolness is, current social trends and beliefs, celebrity, and the opinions of those privileged enough to spend time coming to a consensus about value.

The lemur's trial is meant to dramatize the highly sophisticated groupthink involved in assigning value to art. For me, the far greater value is in the experience of the painting, in the viewer's receptive mind interacting with the art, responding to it as a singular expression. In the end, Maya's repeated interactions with the lemur and his repeated challenges to her are what change her, and this, I hope, is the power of art.

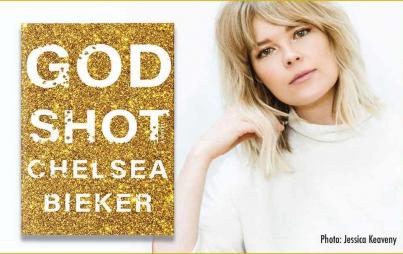

Anita Felicelli is the author of CHIMERICA: A NOVEL (WTAW Press), and the short story collection LOVE SONGS FOR A LOST CONTINENT (Stillhouse Press), which won the 2016 Mary Roberts Rinehart Award. Anita’s stories have appeared in The Massachusetts Review, Terrain, The Normal School, Joyland, Kweli Journal, Eckleburg, and elsewhere. Her essays, reviews, and criticism have appeared in Catapult, SF Chronicle, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the New York Times (Modern Love), Slate, and elsewhere. She graduated from UC Berkeley and UC Berkeley School of Law. She is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. Her work has received a Puffin Foundation grant, two Greater Bay Area Journalism awards, and Pushcart Prize nominations, and has placed as a finalist in several Glimmer Train contests. She grew up in the Bay Area, where she lives with her family.