Judith Scott, who passed away in 2005 at the age of 62, was born with Down syndrome and remained nearly deaf and completely non-verbal her entire life. She was institutionalized for 35 years before her twin sister, Joyce, applied to be her legal guardian. Once reunited, Joyce connected Judith with the Creative Growth Arts Center, a supportive studio in Oakland, California, for adults with physical and mental disabilities. It was here that Judith Scott spent her final 17 years choosing items from the studio around her, then camouflaging them. The results of her labor—densely swaddled amoebas of tightly-wrapped yarn and cloth with objects from clothes hangers to shopping carts at their core—are currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Scott's assemblages are visually complex. They are also contemporary, fitting within the modern "found object" movement using "craft" materials like yarn and working intuitively to create abstract forms.

What makes Scott's art challenging to talk about is that all of the words, ideas and associations attributed to it come from other people—well-meaning people, certainly, like the Brooklyn Museum's thoughtful curators, and the staff of Creative Growth, who introduced Scott's art to big-name collectors—but all people who can only guess at the intent and inspiration behind her work. In all of those dense layers, is Scott burying a memory, or protecting a treasure? What images played through her mind as she wrapped, and why did she choose the things she did to envelop?

In the face of the many questions her sculptures prompt, the little we do know about how Scott related to her own art—like the way she gestured with her hands to indicate that a piece was complete, or the fact that she worked at a table, so that all of her works were envisioned on a flat surface—become clues to mine for meaning. The exhibit honors this by displaying the sculptures on low, flat, broad platforms so that we can see the work, in some small way, as Scott did.

Though Scott cannot tell us how she would wish that we understand her work, the show weaves a poignant narrative about the powerful stories wordless objects—and individuals—may hold.

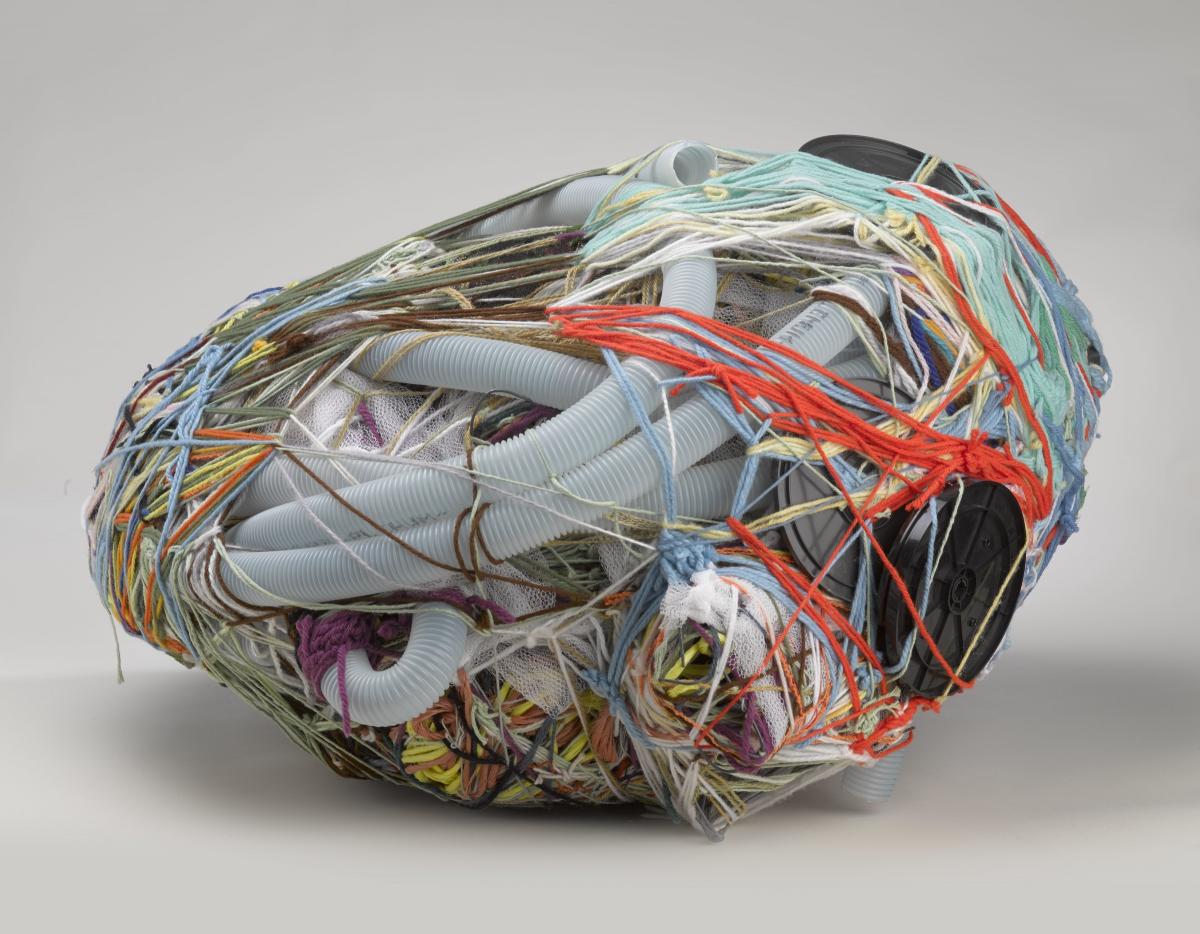

Scott's first wrapped objects were bundles of sticks, but she later took on more ambitious items, like this shopping cart, to adorn and disguise.

Judith Scott (American, 1943‒2005). Untitled, 2003-4. Fiber and found objects, 45 x 47 x 31 in. (114.3 x 119.4 x 78.7 cm). Collection of Orren Davis Jordan and Robert Parker. © Creative Growth Art Center. (Photo: © Addison Doty, Brooklyn Museum)

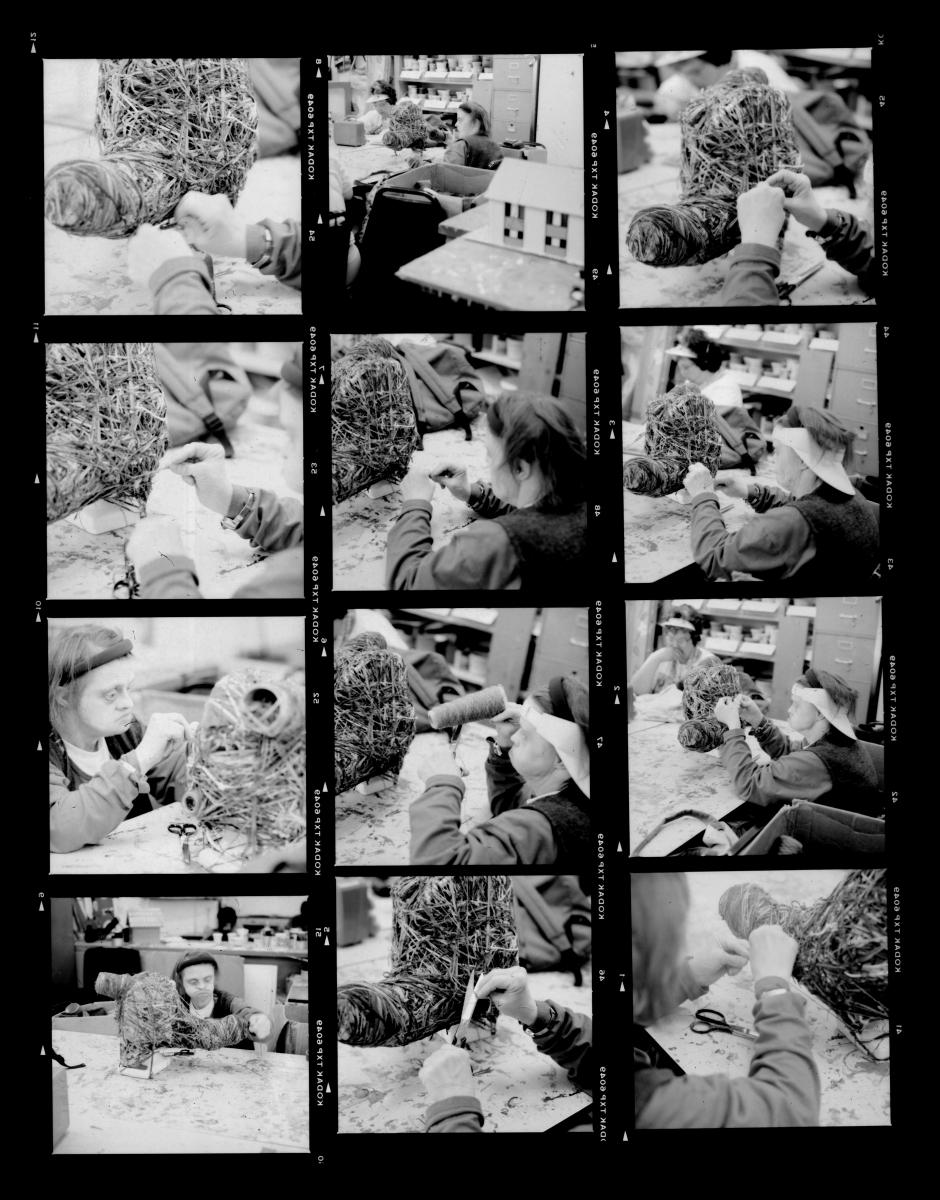

At Creative Growth, Scott worked in an open studio space with several other artists, each creating in their own medium of choice and given freedom to explore and experiment. Creative Growth continues to offer arts programming for individuals with developmental, mental and physical disabilities.

Judith Scott working at Creative Growth Art Center, 1999. (Photos: © Leon Borensztein)

The variety of colors used in this piece make the tight, multi-directional manner of wrapping and binding that Scott employed easily visible.

Judith Scott (American, 1943‒2005). Untitled, 2004. Fiber and found objects, 28 x 15 x 27 in. (71.1 x 38.1 x 68.6 cm). The Smith-Nederpelt Collection. © Creative Growth Art Center. (Photo: © Brooklyn Museum)

In this early work, Scott completely obscures her chosen objects in a dense, sweater-like weave and evocative warm color palette.

Judith Scott (American, 1943‒2005). Untitled, 1989. Fiber and found objects, 37 x 34 x 5 in. (94 x 86.4 x 12.7 cm). Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland. © Creative Growth Art Center. (Photo: © Benjamin Blackwell

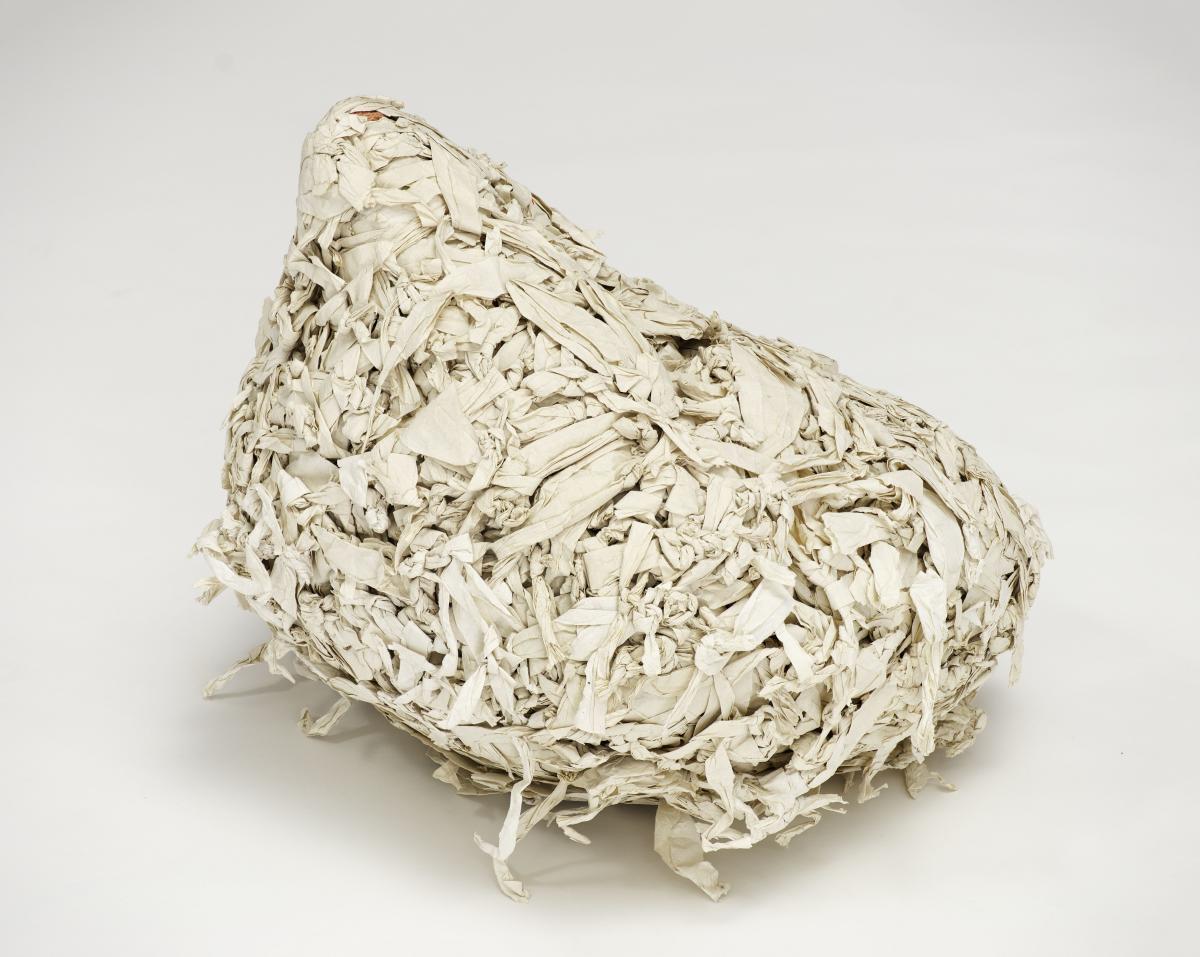

Once, temporarily without access to the materials she traditionally used to make her art, Scott mined the kitchen and bathroom at Creative Growth for paper towels and kept on creating.

Judith Scott (American, 1943‒2005). Untitled, 1994. Fiber and found objects, 27 x 23 x 17 in. (68.6 x 58.4 x 43.2 cm). Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland. © Creative Growth Art Center. (Photo: © Benjamin Blackwell)