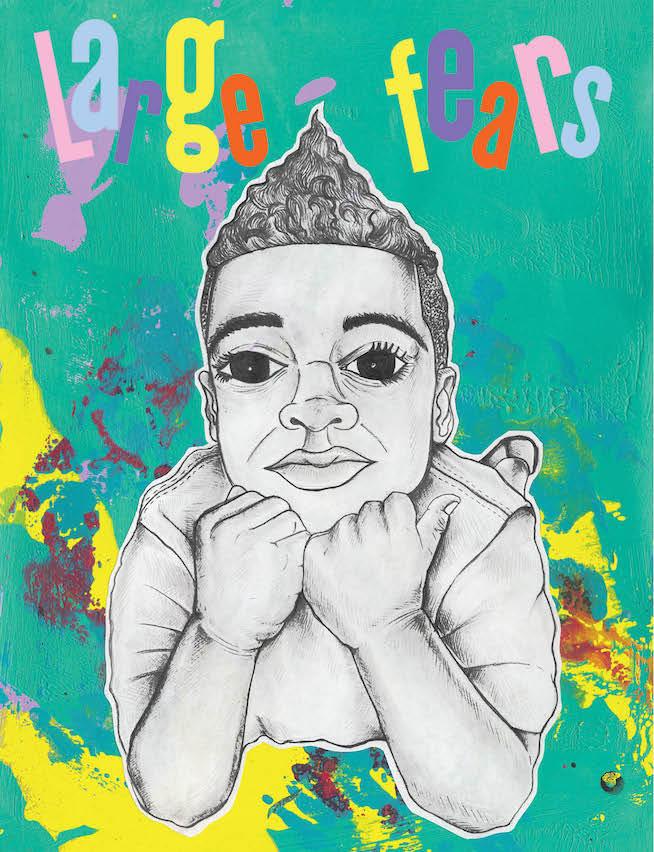

Image: LargeFears.com

It's important for marginalized people to be portrayed as fully human, rather than as stereotypes. And one of the main ways in which marginalized people are stereotyped is through representing them as…well, marginal.

The best books, we like to think, are universal. "To be or not to be" echoes the same for poor Afghanis or wealthy prep school Britishers; you can learn about bullfighting from Hemingway whether you're Ralph Ellison or Camille Paglia (both Hemingway fans). Books aren't bound by time or place or culture. Art is for everyone.

In a passionate Facebook thread last week, children's author Meg Rosoff rejected the idea that there are "too few books for marginalized young people," as librarian Edith Edi Campbell had suggested.

Campbell was excited by the book Large Fears, by Myles E. Johnson and Kendrick Daye, a self-published children's book with a queer Black protagonist. Campbell felt more of such books were needed. But Rosoff countered, "You don't have to read about a queer black boy to read a book about a marginalised child. The children's book world is getting far too literal about what 'needs' to be represented…"

Rosoff is arguing here that marginalized people do not, or should not, get anything from seeing themselves in literature. This is a very big assumption, as Daniel José Older, author of Shadowshaper, told me. "If you have always seen yourself portrayed as the hero in movies and TV shows and literature, you are disqualified from deciding whether seeing yourself matters. Because you don't have the ability to understand what it means not to see yourself," Older explained.

People of color "Have always appreciated and had to draw meaning from our own lives out of books with protagonists who don't look like us," Older added. "But there's so much lost in the translation. You see again and again people portrayed as sidekicks, as villains, as punch lines, and as doomed, always, no matter what part we play."

It's important for marginalized people to be portrayed as fully human, rather than as stereotypes. And one of the main ways in which marginalized people are stereotyped is through representing them as…well, marginal. Queer Black boys are always the helper, never the hero. How can you know that you're the hero of your own story if you're never allowed to be the hero of your own story? "There's a loss of humanity," Older told me. To put a Black queer child at the center of the story is to assert that Black queer children's lives matter, in the teeth of a culture — and literature — that routinely asserts the contrary.

And if Black children's lives matter, then that means they matter to everyone. Rosoff writes, "A great book has a philosophical, spiritual, intellectual agenda that speaks to many people—not just gay black boys. "But why couldn't a story about a gay black boy have a spiritual and intellectual agenda that speaks to many people? If the goal of literature is to expand reader's sense of the world, wouldn't a book about people on the margins be better, not worse, at "teaching kids about the world, about being different, about being brave," which is what Rosoff says books should do?

In Trouble on Triton from 1978, Samuel Delany — a queer Black man—imagined a futuristic "heterotopia." Heterotopia, for Delany, meant a world in which a wide range of differences is allowed and even encouraged. On Triton, gender and sexual orientation can be altered at a whim. Everyone can be everything, and over the course of a lifetime, everyone is.

The hero (or anti-hero) of the story is Bron, a big, blond, action-hero type, familiar from numerous sci-fi space operas. But Bron isn't in a sci-fi space opera — he's on Triton, where he's hopelessly adrift and out of place, precisely because he can't believe that anyone's story but his matters. It's not Bron, but a Black trans man who is the spy who saves the world. It's not Bron, but an elderly gay man who becomes the rock star. It's not Bron, but the female performance artist who finds true love, accolades, and happiness. Eventually, Bron himself decides to undergo a sex change — and becomes the standard White sci-fi female wilting flower — as much of an out of place, retrograde stereotype, as she was when she was male.

Delany's Bron is a deliberate dig at the stereotypical white male science-fiction reader — and for that matter, at the stereotypical white male (or in some cases female) reader of every kind of literature. What would happen to these readers, Delany asks, if they had to look at the heterotopia all around, and had to confront the fact that they were not alone in the universe? Would their minds expand? Or would they simply flail in bitter resentment?

Rosoff presents books as big, inclusive, and appealing to everyone — but how big a universe is it, really, if, in landscape after landscape, planet after planet, a Bron-type character is the only one you see? We need diverse books because, as Older says, the marginalized need to see themselves as the center of their own lives. But we also need them, as Delany suggests, so that the Brons, and Rosoffs, and Berlatskys, no longer see themselves as the protagonist of every story. Art is for everyone — but that means that everyone, whether queer Black boy or Bron, has an interest in getting more people in art.