This doesn't mean that the outcomes of domestic violence are always equal; men tend to be bigger and stronger than women, and therefore are more likely to cause serious harm, even in situations where violence is reciprocal. Still, the fact that women are frequently perpetrators of violence in domestic situations substantially undermines the typical story of domestic abuse—and helps to show just how harmful that story is.

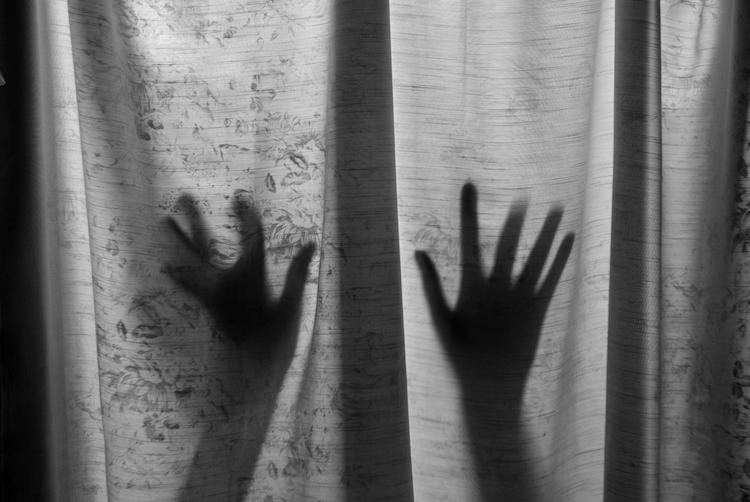

When I was in high school, our teacher showed us an educational film about domestic violence. The guy in the scene was a long, lanky, cadaverous sort, reminiscent (in retrospect) of Nicolas Cage. He was shown sitting at the kitchen table, head in hands, as his wife hectored and badgered him through the lens of woozy, ominous camera effects, so that her face became distorted and inhuman. Finally, the guy couldn't take the camera effects anymore, and snapped in rage, beating her in slo-mo, before recognizing what he'd done and collapsing in tears.

The story is familiar. A strong man is pushed beyond mortal endurance by his instigating wife, who is, tragically, responsible for her own beating. And though I was in high school decades ago, that narrative still has a remarkable amount of credibility, even among those who you'd think would know better.

In a recent piece at the Age, clinical psychologist Sallee McLaren argues that women are "50 per cent" responsible for how domestic violence situations come about. Men, McLaren says, escalate violence, and women fail to prevent them because women don't play enough sports (seriously: she says "Engaging in hard sport with much higher expectations attached to performance would be one important avenue to help girls develop the mental and physical toughness required to stop domestic violence.") Whether because they are shrews or because they are doormats, women's passivity or passive-aggressiveness sends men into paroxysms of violence. Women are culpable for fulfilling their roles as women, thus forcing men to fulfill their roles as men.

There are lots of problems with this formulation (Miki Perkins at the Sydney Morning Herald points out a number of them). But one major flaw in the popular narrative of men and women helplessly fulfilling their preordained gender roles is that it isn't true. Domestic violence isn't uniformly, or even overwhelmingly, a story of men hitting women. On the contrary, violence in heterosexual relationships is distributed almost equally. A 2010 study showed that men make up about 40% of domestic violence victims. A 2001 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found that of the 24% of relationships that were violent, half involved reciprocal violence. Of the half that did not, women were actually more likely than men to be the instigators of the violence.

This doesn't mean that the outcomes of domestic violence are always equal; men tend to be bigger and stronger than women, and therefore are more likely to cause serious harm, even in situations where violence is reciprocal. Still, the fact that women are frequently perpetrators of violence in domestic situations substantially undermines the typical story of domestic abuse — and helps to show just how harmful that story is.

It's easy to see how the typical narrative is harmful to men. Because domestic abuse is seen as a crime against women specifically, men who are abused are often effectively invisible; they are ashamed to speak, and they have few resources available to them. When they do speak out, they may not be believed. The 1in3 campaign says that law enforcement often believes that a male victim is the perpetrator, and may remove him from the home, leaving children with the abuser.

But the unitary narrative around domestic violence hurts women too, as Sallee McLaren's essay shows. If men can't be thought of as victims, women can't be thought of as anything but victims — and victims are roundly despised by just about everyone. Because women are seen as naturally victims, it is easy to blame them for their victimhood. After all, if domestic violence is something that happens to women especially, there must be something wrong with women, especially, that allows them to be victimized in this way.

McLaren concludes that women are not sufficiently forceful and don't stand up for themselves; they need to be taught to be more vigorous, like men. Thus, it's not men who are at fault for domestic abuse, but femininity. Weakness is the culprit, and weakness, stereotypically, is associated with women. Thus, in the name of helping women, McLaren ends up touting male strength, will, and sports. The typical narrative of domestic abuse positions men as powerful and women as disempowered — and so the only way for women to be empowered is to be more like men. The story we tell about domestic violence, by solidifying gender roles, ends up solidifying patriarchy hierarchy as well. Men may be abusing power, but power is manly — and therefore good.

To address domestic violence without glorifying it, then, seems like you need to engage with the fact that men are not the sole aggressors. There's nothing particularly male, or particularly good or powerful, about hitting someone. Individuals of every gender can be cruel, violent, and abusive. If women do suffer more, it's because they are, in general, physically smaller — and also, perhaps, because systemic sexism means women earn less, have fewer resources, and therefore are in more vulnerable positions. But none of that has anything to do with women being weaker-willed or (for pity's sake) with women playing the wrong sports. It's not women's fault for being women that women are abused — and you can see for sure that this is the case because men are abused as well, and it's not their fault when they are, either.