Politicization is sometimes seen as a corruption of art. But it isn't. Art is a way to communicate between people; it exists, and functions, in a social context. Someone makes it and someone views it.

Is all art political?

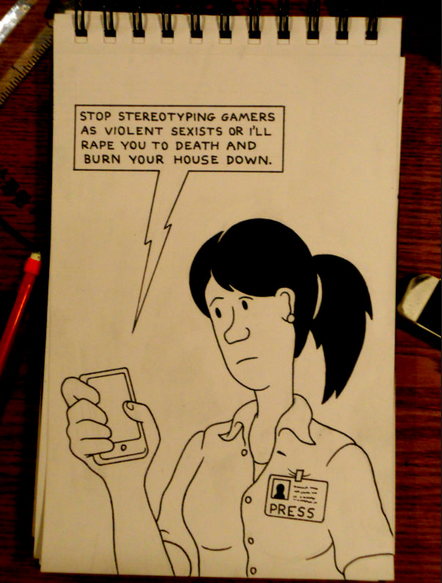

The question is itself an intensely politicized one. It's been debated in various forms for decades, if not centuries. But I started thinking about it again last week when it popped up on social media in relation to Gamergate.

Gamergate began in large part as a reaction against Anita Sarkeesian's videos using feminist criticism to analyze videogames. For Gamergate, that criticism was illegitimate. In part that was because gamergaters disagreed with Sarkeesian's specific claims. But it was also because Gamergate thought that talking about the ideology of games was illegitimate in itself. Sarkeesian was seen as violating the spirit and the purpose of aesthetic endeavors. "Feminised, infantilised, social justice-oriented art sets aside creativity in favour of politics, wallowing in faux victimhood, robbing players of agency and individualism in favour of identity politics and meditations on 'oppression,'" Milo Yiannopolous, a major gamergate figure wrote last November at Breitbart.

Yiannopolous is using deliberate bad faith and slippery terminology here; he has to be aware that championing "agency and individualism" is a political act in tune with the mission of Breitbart, a conservative political site. But beneath, or in addition, to the duplicitousness, I think there's a difference in definition. Before you can decide whether art is political, after all, you have to have a clear idea of what politics is.

People who say art should not be about politics often seem to view politics in relatively narrow terms. As one gamergate supporter said on Twitter last week: "When play game, never think "wonder if this acceptable to feminist", I just have fun, game is escape, art, relax. No politics." Another said, "art that is influenced by politics is called *drum roll* propaganda."

Politics in these cases seems to be defined as explicit messages of support for defined political causes. A campaign slogan is politics; art which includes a campaign slogan would be political art. As long as no character stands up and says, "No feminism here!" or (alternately) "This game cheers on feminism!"—the game is not political. Politics is defined as direct political affiliation. All art does not have a direct political affiliation. Harry Potter, for example, does not tell you how to vote. So Harry Potter is not political.

People who see art as innately political, though, define "political" in a different way. Politics does not have to mean explicit political affiliation. Rather, "politics" means any discussion of, or any thinking about, relationships of power between people. So, for example, Harry Potter imagines a world in which certain powerful people know about dangers which they must keep secret from everyone else. These powerful people even have the duty to tamper with other's minds without consent in order to preserve their secrets. Harry Potter doesn't say, "NSA spying is great!"—there's no explicit political platform. But it has a particular take on power and its relationship to secrecy. In thinking about power, Harry Potter is art about politics.

Yiannopolous in his essay, again, contrasts art about social groups with art that touts individualism and self-sufficiency. In his view, the first is political art which has a platform for social change; the second, since it's platform is against platforms, is not political at all. But, again, if we see politics as being about power relationships between people, it's clear that Yiannopolous' preferred art as political too.

Abstract Expressionism (AbEx) painting, for example, eschews representation in favor of triumphant idiosyncratic artistic effusion—it's about glorifying the individual artist's power, genius and ability to reimagine the world. AbEx privileges the individual over the social, exactly as Yiannopolous wants. And that's a political move; it's a vision of bootstrap Americanism; a kind of heady, aesthetic, Horatio Alger myth. That's why the American government during the Cold War wanted to fund touring art exhibits of AbEx paintings.

Funding for that was slashed by Congress, though. According to Justin Hart in The Empire of Ideas, influential Congress-people saw the modernist, non-representational paintings as too snooty and too East Coast; AbEx to them wasn't virile individualism, but effete affectation, divorced from the social and political norms of America.

The conflict around AbEx demonstrates that art can have different politics depending on the context and the viewer. AbEx can mean the triumphant individual American dream or the dangerous foreign refusal of American community, both at the same time, depending on your perspective. Art, in other words, not only has a take on power relationships, but it is itself embedded in power relationships. Yiannopolous' discussion of how games should not be political inevitably politicizes all games, which are now graded by Yiannopolous and his fans on whether they project the political values of depoliticization and individualization.

This politicization is sometimes seen as a corruption of art. But it isn't. Art is a way to communicate between people; it exists, and functions, in a social context; someone makes it and someone views it. And if art is an exchange of meaning between people, it makes sense that politics—the discussion of power between people—would often be an important part of art. Art and politics, aesthetics and power, exist in the same spaces; they're both social. It's no wonder that they tie around each other and strike off each other, and sometimes, for better or worse, use each other. As when Breitbart grabs onto video games to advance a conservative agenda.

Gamergate claims to decry censorship. But the call for art without politics actually results in a sweeping Puritanism—a carping policing of any meaning beyond a tediously generic "individuality" or "fun" or "shock value." For art to have power, it needs to engage with power, which means engaging with politics. It's true that politics and aesthetics can make a combustible and (Jackson Pollack-style) messy pairing.

But why would anyone want art to be pure, or neat, or safe?