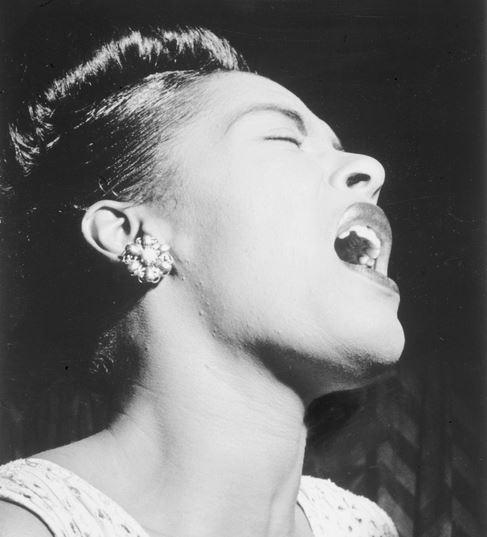

Billie Holiday (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

When people think about the early blues today, they tend to imagine rugged, working-class men with guitars sitting at the crossroads making deals with the devil. Yet according to Paige McGinley's Singing the Blues, the first recorded account of blues, from 1910, describes the performance of Johnnie Woods, a female impersonator; the blues was sung by his ventriloquist dummy.

Woods wasn't an accident or an exception; the image of blues as an expression of authentic, swaggering masculinity is a latter-day myth, promulgated by such performers (impersonators?) as Mick Jagger and Robert Plant. Originally, though, blues and the closely related form of jazz embraced a much wider range of gender expressions and sexualities. Blues and jazz were marginal forms in the early 20th century not just because they were African-American, but also because they dealt explicitly (and sometimes very explicitly) with queer expression and gender play. Johnnie Woods was only the beginning. And arguably Woods wasn't even the beginning.

Here's a rundown of some of the most influential queer figures in blues history.

Ma Rainey

Ma Rainey was supposedly performing as early as 1902, though she wasn't recorded until the 1920s. Rainey was a hugely popular figure—and she was infamous for her bisexual exploits, including one notorious 1925 incident in which her home was raided by police during a lesbian orgy. Rainey's "Prove It On Me Blues" is an acknowledgement and a challenge; Rainey both declares her interest in women and dares the listener to recognize it, with more than a bit of a takes-one-to-know-one taunt. "They say I do it, ain't nobody caught me/Sure got to prove it on me; Went out last night with a crowd of my friends/They must've been women, 'cause I don't like no men," she declares. The record's cover, showing Rainey in a rakish butch hat and vest approaching a couple of other women, is similarly blunt.

Frankie Jaxon

Frankie "Half-Pint" Jaxon was an important influence on later performers like Cab Calloway and on contemporaries like Bessie Smith. Like Johnnie Woods, he was also known as a female impersonator. In "I'm Gonna Dance Wit De Guy Wot Brung Me" he sings both the male and female parts, in a high camp tour de force.

Jaxon's cross-dressing wasn't a novelty—or, perhaps more accurately, it was an established and much enjoyed novelty in Harlem Renaissance culture. As Interstate Tattler, the black weekly, wrote of the costume balls at Rockland Palace: "Of course, a costume ball can be a very tame thing, but when all the exquisitely gowned women on the floor are men and a number of the smartest men are women, ah then, we have something over which to thrill and grow round-eyed."

Bessie Smith

"There's two things I can't understand/that's a mannish actin' woman, and a skipping, twistin' woman-acting man," Bessie Smith declares. Her confusion is overstated, and maybe deliberately ironic: Like her musical mentor Ma Rainey, Smith had numerous sexual relationships with both men and women, and was quite familiar with gay and lesbian subcultures. In that context, Smith's song about why her man is no good becomes (like Rainey's above) also a song about looking for other options.

Billie Holiday

Holiday was famous for songs of heterosexual heartbreak. Lyrically she rarely flirted with homoerotic material as did Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, and her only references to lesbianism in her autobiography are derogatory. However, like Rainey and Smith, she was bisexual, and had a number of relationships with women. The most famous of these was probably an affair with actress Tallulah Bankhead, which inspired a marvelously catty letter after the breakup. Bankhead was apparently unhappy with her appearance in Holiday's memoir. Holiday responded:

"While I was working out of town, you didn't mind talking to Doubleday and suggesting behind my damned back that I had flipped and/or made up those little mentions of you in my book. Baby, Cliff Allen and Billy Heywood are still around. My maid who was with me at the Strand isn't dead either. There are plenty of others around who remember how you carried on so you almost got me fired out of the place. And if you want to get shitty, we can make it a big shitty party. We can all get funky together!"

Billy Strayhorn

Billy Strayhorn, pianist and writer with the Duke Ellington orchestra, was openly gay. It's been suggested that he was content to stay in the background of the Ellington orchestra in part because he did not want attention drawn to his personal life, but that's been disputed. Certainly, as the video above makes clear, Strayhorn was perfectly comfortable performing (here on one of his most famous tunes, "Take the A Train"). Strayhorn was partners with pianist Aaron Bridgers in the 1940s, and close friends with Lean Horne (he was the love of her life, according to some accounts).

Langston Hughes

Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes wrote many poems inspired by jazz and blues forms and subjects, though his take tended to be less sexually raucous than Ma Rainey's. Hughes' private life was also much less public than Rainey's—but most scholars believe he was gay, and he did write sympathetically about gay characters in a number of his works. For example, in "Café: 3 AM," he wrote:

Detectives from the vice squad

with weary sadistic eyes

spotting fairies.

Degenerates,

some folks say.

But God, Nature,

or somebody

made them that way.

Lucille Bogan

Bogan specialized in shocking, filthy, scandalous blues: "I've got nipples on my titties the size of my thumb/I've got something between my legs that'll make a dead man come," is one of her more notable lyrics. "B.D. Woman Blue" refers to bulldagger or bull dyke, slang for lesbian. "Comin' a time, B.D. women they ain't going to need no men," is a message in Bogan's usual direct style.

Gay performers, and sometimes gay subtext, continued to be a part of blues and jazz and their derivatives. Performers like Big Mama Thornton and Little Richard were central to early rock, for example, as Ma Rainey and Billy Strayhorn were central to early blues and jazz. That history has often been obscured though, so that, for example, the mixture of gay and African-American influences in disco was seen at the time as somehow alien to, or outside of, the blues/rock lineage, rather than as a natural part of it.

But in fact, the history of pop music in general, and of black pop music in particular, has always been gay history. Ma Rainey will prove it on you.