Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Beyoncé, according to Mike Huckabee, is "mental poison." By this he means that she will get into your mind and make you think about sex. Huckabee was shocked that the Obamas let their daughters watch Beyoncé videos, which he felt were "best left for the privacy of her bedroom." Along the same lines, but from the opposite side of the political spectrum, feminist scholar bell hooks last year looked at Beyoncé's risque cover for Time magazine and recoiled. "I see a part of Beyoncé that is in fact anti-feminist—that is a terrorist, especially in terms of the impact on young girls," hooks said.

Right and left agree; Beyoncé's sexiness puts the young (and especially young black girls) in danger.

This confluence across the political spectrum isn't new; while they can't agree on much, elements of the left and right have always been able to build bridges over sexy bodies and their shared dislike of same. Radical feminist Andrea Dworkin declared back in the 1980s that "the civil impact of pornography on women is staggering. It keeps us socially silent, it keeps us socially compliant, it keeps us afraid in neighborhoods, and it creates a vast hopelessness for women, a vast despair." Edwin Meese, Reagan's conservative attorney general, concurred: "There are empirically verifiable connections between pornography and violent sex-related crimes," he argued. Sex in the media, for Dworkin and Meese, is connected directly to social violence. A nude body on display can hurt you.

Sex-positive feminists like Susie Bright on the left and libertarians like the folks at Reason on the right have spent decades arguing against this position. Usually these arguments are based around notions of personal autonomy, free speech, and respect for the sexual choices of consenting adults. Anti-sex arguments (in general) focus on social harm (leading to individual harm). Pro-sex arguments (in general) focus on individual rights (leading to broader social goods).

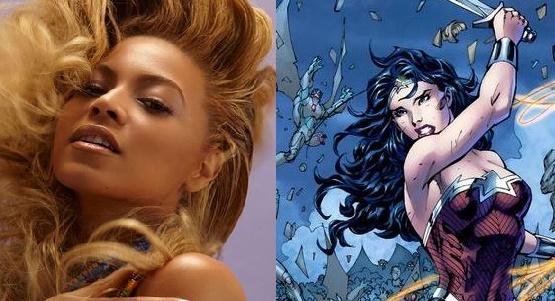

There is, however, another possible tack. Rather than seeing Beyoncé as an autonomous adult, you could see her as . . . Wonder Woman.

The Superpower Of Eroticism

Most people recognize Wonder Woman and her iconic swimsuit, but know little about her. And in fact, her more modern iterations (including, alas, the '70s Lynda Carter television show) are not especially different from those of many another sexy/strong female action hero.

As I discuss in my book Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism, Wonder Woman's early comic book adventures were something else again. Psychologist, polyamorist, and gender theorist William Marston, along with artist Harry Peter, created the most sexually adventurous comics ever penned for eight-year-olds. Enthusiastically detailed bondage scenes appeared on virtually every page, including one sequence with Wonder Woman in a gimp mask musing on the history of restraints in France. The comic also delighted in elaborate lesbian role-play scenarios, including one in which the Amazons on Paradise Island dressed in deer outfits, tracked each other down, trussed each other up, and pretended to eat each other. Cross-dressing and hypnosis abounded.

Some people at the time, understandably, were concerned about all this kinky bondage play being served up to young children. The advisory board of National Comics, Wonder Woman's publisher, expressed concerns about the copious kink. But Marston defended his work in a letter to his editor—not on the basis of free speech, but rather on the grounds that erotic imagery was necessary for social salvation:

"The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound . . . Only when the control of self by others is more pleasant than the unbound assertion of self in human relationships can we hope for a stable, peaceful human society . . . Giving to others, being controlled by them, submitting to other people cannot possibly be enjoyable without a strong erotic element."

Eroticism—particularly of the kinky sort—didn't lead to violence for Marston. On the contrary, eroticism provided the enticement needed to tame man's (and for Marston, it was especially man's) violent impulses. Thus Marston's creation of Wonder Woman's magic lasso, a yonic symbol that he described as representing "female charm, allure, oomph, attraction" and the power that "every woman has . . . over people of both sexes whom she wishes to influence or control in any way." Note that the lasso originally was not a lasso of truth, but a much more useful lasso of control—and also note that Marston was very aware of lesbian possibilities. Female sexual appeal could seduce not just men, but people of every gender, to peace.

You can see Marston's vision clearly in the sequence below from Wonder Woman #4, in which Wonder Woman's image is beamed into the brain's of recalcitrant industrialists. The sexy female media figure pacifies them, so that Wonder Woman becomes their "love leader" (to use the term Marston preferred in his psychological writings). They then become useful members of society. Sex doesn't lead to death and terror, but to sexually fulfilling social productivity for all.

Obviously, Marston was something of a crank, and you'd hardly want to adopt his theories wholesale. Even Wonder Woman in that last panel isn't so keen on being "commandress over a lot of men." And who can blame her? Women's bodies aren't some sort of pacificatory state resource, and it's hard to imagine that anyone—right, left, or center—would really want them to be.

Still, Marston provides us with some different and useful ways of thinking about representations of sex and sexuality. Rather than seeing Beyoncé's sexual performance as linked inevitably to terror and destruction, we can consider whether, instead, eroticism might be an alternative to violence. At the very least, it seems worth asking who is linking sex to terrorism and poison. Is it Beyoncé? Or is it her critics, whether on the right or left? And if the latter, what sort of world are they envisioning, in which love equals death, rather than life? Perhaps Beyoncé isn't Wonder Woman, love leader. But surely, Beyoncé as Wonder Woman makes more sense than Beyoncé as death's head.