Since the '60s at least, rock has been seen mostly as music for and by disaffected, angry white guys—shaggy haircuts and British accent optional. It's all about testosterone swagger and raging against the machine by miming the styles of marginalized racial groups—which presupposes that you're not actually a member of those marginalized racial groups yourself.

Thus Rolling Stone, that old-school rock mouthpiece, has only one album by a black man in its top 10 greatest albums of all time, and none by black women (in fact, the first black woman to register a mention is Aretha Franklin, way down at number 83). Other similar lists often have no one except white guys in their upper echelons, either.

It's true that there have been lots of great white male rockers, from Dylan and the Beatles through Zeppelin and the White Stripes. But is it true that the genre is completely dominated by just white guys? Obviously some folks think so. But I'd argue that that's because of how the genre is defined, and how genres in American music in general are defined.

Many of the authors of the essay collection Hidden in the Mix, about African-Americans in country music, point out that country, as a genre, defines itself in part by whiteness. Many black performers have contributed to country, but because they're black they are seen as marginal, or not exactly country. For example, Ray Charles' Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music was one of the best-selling country albums of all time—but is almost never listed as such because Charles is not seen as a country performer.

There are a couple of token exceptions—Charlie Pride in country, Jimi Hendrix in rock. But in general, genre boundaries are conscious of race—and, in the case of rock, conscious of gender too.

This shouldn't be a surprise; the American popular recording industry began by using race as genre, separating race records from hillbilly titles on the basis of skin color rather than style. But maybe after a hundred years, it's time to rethink that particular tradition? As Dee at blackrocktubmlr often point outs, the association of rock with white maleness has meant folks who aren't white males often aren't recognized as rock stars—either because they're categorized as some other genre (like R&B or funk) or because they're just forgotten altogether. Black women especially often get erased. Rock guys like Howlin' Wolf and Chuck Berry are venerated, while performers like Rosetta Tharpe and LaVern Baker are passed by.

In an effort to rock the canon, below is a list of great black women rockers, from the 1950s to the present. There are plenty more where these came from— but you've got to start somewhere.

Lady Bo (Peggy Jones), "Roadrunner"

Lady Bo, or Peggy Jones, was the lead guitarist on many of Bo Diddley's early hits, including the typically grunge-soaked "Roadrunner." The ax sounds like it's being hammered by some frightening industrial process. Somewhere Kim Gordon is still de-tuning her guitars in solidarity.

Mickey and Sylvia, "No Good Lover"

Sylvia Robinson is best known as the founder and CEO of the Sugar Hill Records Label, which released many of the most important early rap singles, including the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight" and Grandmaster Flash's "The Message." Long before that, though, she teamed up with guitarist Mickey Baker to create some of the hippest early rock singles, including this he said/she said number, where Baker's lead lines sound almost as dirty as Robinson's growl.

Candi Staton, "Love Chain"

If Rod Stewart or Eric Burdon were singing, this would almost certainly be considered rock. Since it's a black woman with a tougher voice than either of them, though, it generally gets shelved in soul. Whatever you call it, though, it's an amazing track, with Staton staking her claim as the definitive Muscle Shoals singer.

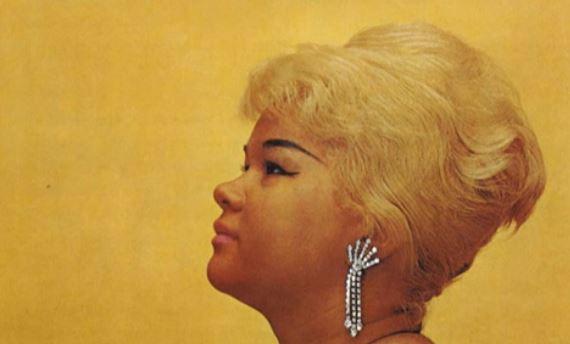

Etta James, "Let's Burn Down the Cornfield"

James is best remembered for her early rock and roll recordings like "The Wallflower," and her '60s soul sides like "I'd Rather Go Blind." This Randy Newman cover from the '70s is less well-known but just as fine—her voice is all pain and menace and lust, set off by a fuzzed-out blood-soaked blues-rock guitar solo.

Betty Davis, "Walkin' Up the Road"

A track from Davis' self-titled 1973 classic. As with soul, funk often seems to be defined as much by what color the singer is as by the content of the music. You can certainly hear James Brown here, but you have to think that the Rolling Stones would have been happy to record it if they could manage this level of intensity.

Rufus, "Maybe Your Baby"

Chaka Khan makes a strong case for Stevie Wonder as a rock artist by covering his "Maybe Your Baby" with even more swagger and fire than the original.

Minnie Riperton, "Every Time He Comes Around"

Stevie Wonder himself collaborated on Riperton's 1974 album Perfect Angel. The album is an uncategorizable mix of rock and folk and soul, paralleling the work of other idiosyncratic hybrid geniuses like Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. The blistering guitar workout, though—shadowing Riperton's powerhouse vocals and whistle-notes—makes this track definitively rock.

Mother's Finest, "Truth Will Set You Free"

Mother's Finest manages to hold up the lighter for both disco and hair metal at the same time, while nodding back to doo-wop and gospel. Joyce "Baby Jean" Kennedy is criminally forgotten; surely someone out there could sample this and take it to the bank.

ESG, "Moody"

New wave funk hipster weirdos ESG recorded a series of uncategorizable, alienating albums in the '80s; this is from their first, 1983's Come Away With ESG. "Rock" is often used to mean "pop music that doesn't fit anywhere else" and ESG certainly qualifies on those terms. In comparison, the Talking Heads sound sedate and Kraftwerk sounds somewhat human.

Brandy, "Necessary"

Nineties pop phenom Brandy had her best album in 2004. Afrodisiac was mostly a collaboration with Timbaland, but Cee-Lo turned in the boiling psychedlic production for this jam. If "Whiter Shade of Pale" is rock, this certainly qualifies.

Valerie June, "You Can't Be Told"

These days rock is mostly a retro style, like blues—and in fact, retro blues outfits like Trampled Under Foot are often indistinguishable from retro rock. Valerie June works in a bunch of roots styles—folk, country, blues—but "You Can't Be Told" sounds like it fell out of the '70s arena circuit. ZZ Top wishes they were still making music like this.

SZA, "Sweet November"

Left-of-center R&B artists like FKA Twigs and Kelela have been moving toward a fusion with alternative indie rock for the past couple of years. SZA's "Sweet November" is a prime example; it could as easily be dream-pop as soul, and puts the two together so seamlessly that you wonder if they were ever really separate.

Again, there could be a ton more examples here; if Candi Staton and Etta James, why not Aretha? If Mother's Finest, why not Donna Summer? If Valerie June why not Odetta? If Brandy, what about Beyoncé? Once you realize rock doesn't have to be all white guys, the tradition starts to look a lot broader, a lot more inclusive, and a hell of a lot more interesting.