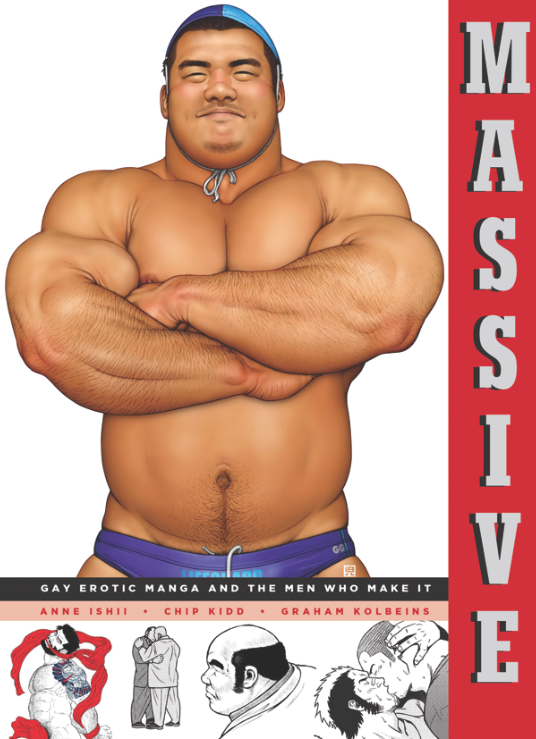

Fantagraphics' new anthology, Massive, edited by Anne Ishii, Graham Kolbeins and Chip Kidd, focuses on a world of comics unfamiliar to most readers in the U.S.: gay manga. Manga, or Japanese comics, has made major inroads into American consciousness over the past 20 years, and the subgenre of yaoi or boys' love—male/male romance written mostly by women for women, and mostly featuring languidly androgynous pretty bodies—has been unexpectedly popular.

But gay manga titles by and for gay men have had much less mainstream success, and few official translations. This collection, then, is a window onto an unfamiliar world—especially for a heterosexual semi-Luddite like myself, who hasn't spent time in the online spaces where images and sequences from these comics are traded in bootleg translations.

Some of Massive does seem to come, if not from a galaxy far, far away, at least from a recognizably different culture and aesthetic. Kumada Poosuke's four-panel humor strips rely on fetish gags that are well-nigh incomprehensible to the uninitiated. One strip called "Winter Thrills," for example, involves a cute, cartoony character talking about how he loves to wear winter clothes; then another character talks about his winter socks, and out of nowhere declares in the last panel, "My feet are next level musky!" That's the whole joke. Its non-jokeness is kind of funny—but in the way that kids' jokes can be funny because they don't quite work—along the lines of "Knock knock. Who's there? Smelly feet! Smelly feet who? Smelly feet! Next level musky smelly feet!"

One way or the other, relevant cultural information has gone astray.

But most of the comics in Massive don't feel anywhere near that alienating. Instead, they're surprisingly familiar. The over-muscled, nude male bodies, for example, aren't so different from the over-muscled, virtually nude male bodies you often see in superhero comics. Some of this no doubt is shared influence; Tom of Finland (the celebrated Finnish homoerotic artist) is probably a (more or less surreptitious) inspiration for both, and shonen manga styles (adventure comics for boys and men) are also a common referent.

The hotties in Takeshi Matsu's high school sex goof "Kannai's Dilemma" share—not so surprisingly when the smoke clears—improbable six packs with Green Lantern.

Jiraiya's bulky cavemen look not a little like the Incredible Hulk.

The narratives are familiar too. In some cases, that's just because porn is porn; Seizoh Ebisubashi's school administrator vignette has the, fantasy-world-where-everyone-just-decides-to-have-sex plotlessness of X-rated material in any medium the world over. In other cases, though, the sense of recognition lies in that fact that genre narratives and erotic gay content click seamlessly together.

Gengoroh Tagame, one of the most influential creators in gay comics, starts the collection off with an excerpt from his famous "Do You Remember South Island P.O.W. Camp?" The story involves a Japanese P.O.W., desperate to obtain quinine for his sick companion. He ends up begging for help from the camp C.E.O., leading to a brutal sequence of tortures. The super villain violence and sexualized sadism wouldn't be too far out of place in a superhero narrative or a James Bond film (Skyfall made that connection explicitly), or in a romance like Outlander, for that matter.

Even more telling is Jiraiya's humorous Caveman Guu, in which Guu beats up a bunch of other cave-guys in order to rescue a cave-girl. The rescued maiden declares her love for him . . . but his bits aren't interested, and instead he ends up having passionate intercourse with the guys he's just thumped.

The great thing about that isn't that it violates genre expectations, but that it fulfills them. As Eve Sedgwick wrote in her classic study Between Men, women in Western literature (and it seems in Japanese as well) are often just a very convenient cover for male-male relationships; guys fight over women's affections so they don't have to admit that they are actually fighting over each other's attention and interest.

The damsel in distress in adventure fiction really is generally an afterthought; the relationship between hero and villain really is the central point of emotional investment. Jiraiya's story isn't so much subverting tropes, as revealing them.

Rather than being a window into a distant culture, then, Massive shows that gayness isn't alien. That doesn't mean that Green Lantern or adventure narratives are really gay, or that the truth of them is a hidden homosexuality: There's nothing hidden or secret about the gay content in Massive, after all.

But Massive does suggest that male erotics, or the fetishization of the male body, is more common than we tend to think. In our culture, it's women's bodies that by default are seen as sexualized—tendencies which can lead to a view of women as nothing but fetish objects. Massive serves as a reminder that guys are objects, too, and that the way we see and the stories we tell figure male bodies as sexual, even in a mainstream culture that is reluctant to admit as much.

To read Massive isn't to discover a hidden truth, but to see a massive, obvious fact—bulging out for all the world to see.

Green Lantern courtesy of splicetoday.com; Hulk courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; all other images via Fantagraphics