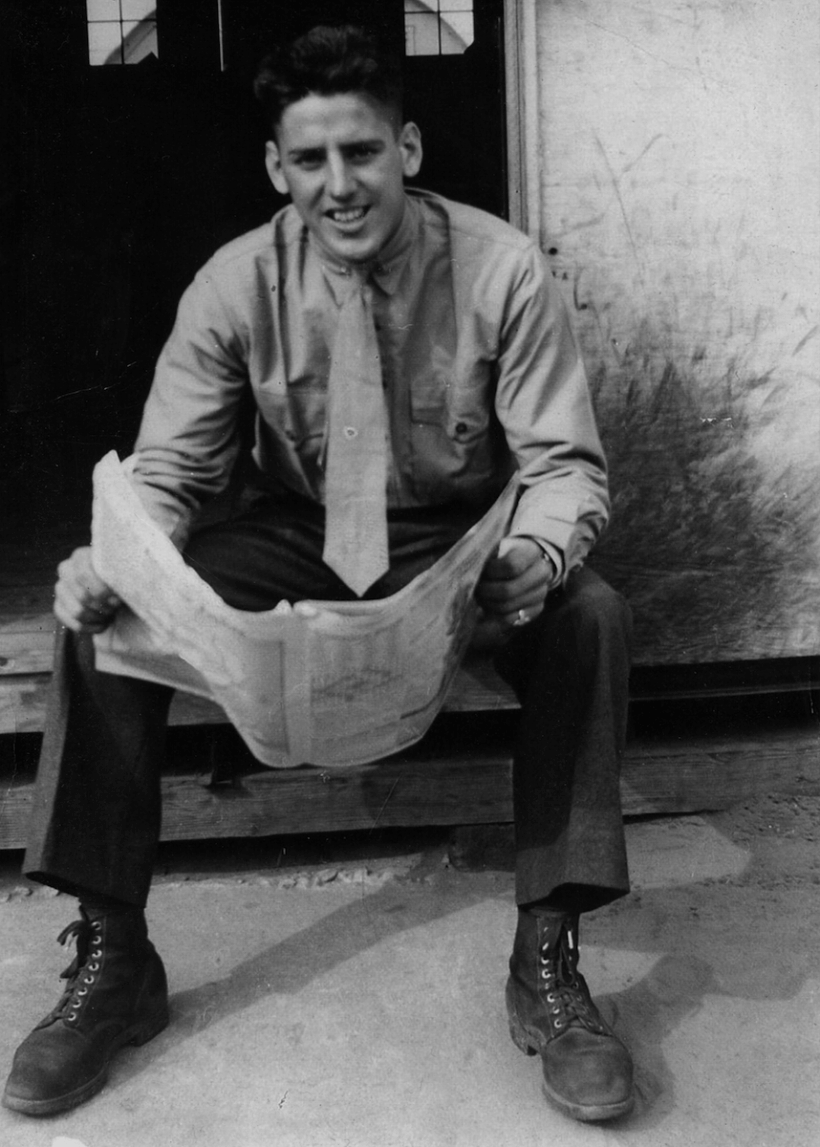

World War II veterans suffered acutely at the hands of a society intent on a single conformist vision of life that did not include mental illness. (Image of Pat courtesy of the author.)

Long Reads is a bimonthly feature, showcasing long-form essays.

“Would you like me to buy you an ice cream?”

Rina stopped arguing with her boyfriend and looked up. Standing upright before her was a man with a wide smile and broad shoulders. It was 1939, and they were on a bus full of chattering Brooklyn fraternity and sorority members.

The man stared at Rina. There was a momentary pause.

“Yes,” Rina said.

(“Somebody offers me an ice cream, I’ll take it,” she would observe later.)

The man plopped down on the seat beside Rina. To the Alpha Delta Pi sorority sisters, he was a catch: good-looking (if not very tall), joke-telling, friendly. The two talked. All along the parkways and highways, through small towns and fields, they drove for hours. They arrived at Bear Mountain, got ice cream, talked some more.

Over two decades later, in their bed in a low flat California house, sometime around midnight, the man wept relentlessly.

Sunny Sicilian Frat Boy Meets Death

When my grandmother tells stories about my grandfather, the specter of madness lurks in the corners like a creature in a gothic novel. Sure, there’s the smiling, confident guy who butts into a date. But inevitably my grandmother will make a throwaway comment about some darker, more troubled, atypical behavior.

My mother didn’t want to speak about her father’s darkness — didn’t believe it existed. But the hidden stories bothered me. I couldn’t reconcile these conflicting pictures of my grandfather. What happened to him between the encounter on the bus in 1939 and his death in 1974? What caused his weeping?

Madness is a word that both obscures and dehumanizes. I wanted to move away from it. I wanted not these glimpses of the creature in the corner but the real story, the human story. The truth.

I’m not sure why I felt so compelled to understand the truth of my grandfather. Maybe it was because he functioned in my life as a picture book character from my childhood, popping up in my mind in brief flashes, but which I never could recall fully.

I didn’t realize the extent of buried pain I would uncover, extending far beyond my own family’s secrets. World War II veterans suffered acutely at the hands of a society intent on a single conformist vision of life that did not include mental illness. Mothers, girlfriends, wives, and other family got wrapped up in the lingering casualties of war. My grandfather Pat’s story can be seen as a symptom of societal prejudice — yet his unique variety of anguish has shaped my family to this day.

Long before Pearl Harbor, Pat lived a carefree life: Brooklyn Dodgers games, economics classes, weekends at the movie theater, running around with a group of fellow Southern Italian fraternity brothers. And dancing, always dancing.

♦♦♦

“There’ll be bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover,” Ray Eberle crooned as Pat swayed on the dance floor with his future wife, the woman from the bus, Rina. In Rina’s parents’ living room, he held her close, as the ballads of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey played softly. They nestled against the heavy brocade drapes hung across the bay window. On the table was the coffee cake with raisins Rina’s mother has made.

Then suddenly Pat twirled Rina all around. They were so good they once won a dance competition, Rina says.

“Tomorrow, just you wait and see,” sang Eberle. “There’ll be love and laughter and peace ever after, tomorrow.”

♦♦♦

On a December Monday in 1941, Pat sat in a classroom at Brooklyn College. The president of the college got on the loudspeaker. The House of Representatives was voting on the war. Pat listened as congressman after congressman voted yes to a declaration of war on Japan.

When the Marine Corps recruiter came to campus, Pat signed up. Little did he know what change the next four years would wreak on his life.

♦♦♦

Compared to previous wars, World War II fostered some unique circumstances that primed soldiers for distress. Instead of clearly-demarcated battles and battlegrounds, death could come at any time in spontaneous attacks. Many soldiers didn’t feel motivated to keep fighting for the war’s lofty moral principles but by the bond with their “buddies” — making the death of those friends even more painful.

And given censorship designed to maintain a patriotic vision of the war for those back home, letters from loved ones seemed to offer no comprehension of the hell American soldiers were living.

Rina remembers the war as a fearful but exciting time. Pat’s letters from the South Pacific would arrive in big stacks after two weeks.

“Dear honey, I miss you,” they’d begin. Then would come lines and lines of blacked-out text. “Can’t wait to get home, miss you, love you,” they’d conclude.

On the radio, Rina heard that Pat’s unit had helped secure the Orote Peninsula, a Japanese stronghold on Guam. She wrote to him how happy she was to hear it. “Don’t believe everything that you hear or see,” he replied. “We lost more men than in any other combat.” (Indeed, at that point in the war, the Battle of Guam produced the second-most number of Marine casualties.)

For American veterans in between, of the so-called “Greatest Generation,” suffering was considered anathema to patriotism, progress, and masculinity. Still, they suffered, secretly... A man who did not conform — even if his mental health prevented him from doing so — was considered a societal failure.

In the winter of 1945, the doorbell rang at Rina’s parents’ house. “I nearly dropped my teeth,” she recalls. There was Pat, duffel bag in hand. He moved in with the family, and they got engaged.

The depressive symptoms started soon after that. Now, Rina doesn’t recall most of them. “Maybe I don’t want to remember,” she says. But once, while Pat was still staying at her house, she noticed a bottle of “iodine or something” missing. “Maybe he’s trying to commit suicide,” she thought.

A couple of months into 1946, she got him placed in one of the most well-respected national psychiatric wards, at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center.

On the way to the ward, Pat’s father cried, remembering when he brought his wife — Pat’s mother — to a mental institution. He never imagined having to take his son.

Evil Mothers, Neurotic Soldiers, And Savvy Psychiatrists

I sat in libraries and flipped through yellowed pages about depression and the war, searching for clues as to what my grandfather might have experienced.

World War I had shell-shock: a combination of tics, paralysis, sleep problems, and memory loss that doctors at the time considered a fairly normal bodily (not mental) response. Vietnam came to be associated with PTSD, short for post-traumatic stress disorder, a collection of physiological and psychological symptoms caused by an out-of-the-ordinary trauma — such as war, cried thousands of American protestors.

But for American veterans in between, of the so-called “Greatest Generation,” suffering was considered anathema to patriotism, progress, and masculinity. Still, they suffered, secretly, the soldiers of World War II (1941-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953). I found that Pat’s America put stringent requirements on returning soldiers. A man who did not conform — even if his mental health prevented him from doing so — was considered a societal failure.

Although the American military had implemented a highly-touted new psychological screening system for World War II, soldiers still experienced “combat stress reaction,” “traumatic war neurosis,” “combat exhaustion” and other conditions that included debilitating anxiety attacks, sleep disturbances, and startling easily. In fact, according to historians, many Americans believed that U.S. troops broke down more frequently than other Allied and Axis soldiers.

Pat spent months in and out of institutions. He was medicated. He might have also undergone talk therapy, sedation, hydrotherapy (involving submersion in baths), or electric shock treatment — all common practices in mid-1940s psychiatric treatment.

Their engagement off, Rina didn’t see him from the summer of 1946 until 1948, when she went to his father’s funeral. Afterward, he called to invite her to the movies.

They were married two years later. “He was back to his old self.”

A few years into the marriage, the symptoms began again. They’d go out with friends on special occasions to fancy restaurants, where well-known entertainers sang. Pat would fall asleep halfway through the conversation. In the middle of the night, he couldn’t sleep and would start sobbing. Nobody really noticed, save for one keen-eyed friend.

“They just saw the Pat they knew,” says Rina. “If you’re not looking for something, you don’t see it.”

What many people also didn’t see in the 1940s and 1950s was that, just as troops clashed overseas, American psychiatrists waged a war of their own. In trying to explain why so many American soldiers experienced psychological problems, these psychiatrists would ultimately trap veterans like Pat, reducing their lives down to a single societal script.

The battleground question was this: Did veterans’ mental distress result from war’s disturbing and intimate experience of death — or a pre-existing disposition to dysfunction wrought by the family?

You Might Also Like: Lest We Never Forget: My Grandfather's Holocaust Story

Psychiatrists believing the latter won. Experiencing peak popularity in the years directly following World War II, psychiatrists initiated a massive campaign to rewrite the story of American society. They argued that broken-down soldiers were mere symptoms of the most significant crisis to ever face the United States: the overprotective mother.

That’s right: the mother, and often girlfriend or wife, too. “Mom” — if not coached by proper male authorities — smothered her sons, turning them into weaklings who couldn’t stomach battle. “Anxiety is a symptom of demoralization, of yielding to the enemy’s commands,” wrote one psychiatrist in the years following the war, suggesting that soldiers with mental health problems were cowardly. According to psychiatrists, this loss of masculine virility plagued not just soldiers’ minds but American life in general.

Men’s magazines, radio plays, and psychiatrists’ pamphlets told returning soldiers that they were unpatriotic, weak, and unmanly if they did not immediately reintegrate into civilian life, take jobs, and relegate women back to their homes and their place. A woman’s role was to serve as helpmeet, lavishing affection on her soldier to help with the reintegration process.

Perhaps Pat, too, blamed his mother, not only for dastardly “Mom” traits but also for her history of mental instability and hospitalization. Regardless, he was constantly in and out of work. Rina took on extra jobs to compensate: sales, tutoring, babysitting. It drove her crazy when Pat would sit in the living room, saying to the kids (there were kids now), “Why is she working? Why isn’t she taking care of her babies?”

Finally, Pat was offered a job as a contracts administrator in Southern California. They moved; they bought a one-story ranch house and planted a fig tree. But soon enough Rina overheard him on the phone calling up his old boss, saying he hated his work and living in California.

Then he lost the job.

Pat would “cry and cry,” Rina says. “And lose his jobs. And that was the story of our life.”

A Time To Weep

My aunt and mother remember their father differently. Sure, he lost jobs, but he also worked in aerospace, an industry in the early 1960s prone to laying off workers in between contracts or boom cycles.

He was a musical guy, who in New York sang first tenor with Rina at local elementary school musicals. Just like before the war, you could always find him dancing. He was a fanatic for bridge and had the patience to teach his children to drive stick shift.

On Sundays, he took Susan to get orange soda and whipped cream chocolate éclairs. On Thanksgiving, he played touch football with Vicki, even though many girls weren’t encouraged or often allowed to play sports. They’d run to and fro across the grass, out of breath underneath the low-hanging branches of a tree in the corner of the yard.

“I could count on my father,” says Vicki.

“I always envision him smiling,” says Susan.

What the daughters don’t recall much about is their father’s mental health. Vicki does remember Pat going through depressive spells, when he was more withdrawn.

“It’s just a vagueness,” she says of her intuition that the war might have done something to her father’s mind, or that depression ran in the family. The specter of madness emerged when she was young and haunted family stories ever since.

In trying to unearth the secrets of my grandfather’s story, these kinds of contradictory narratives confused me at first.

But given all I was learning about the behavioral rules World War II veterans were expected to follow, I began to see how and why he might have kept his suffering as secret as possible. I started finding out about psychiatric treatments in the 1960s, discovering how my grandfather might have tried to deal with that suffering. I was also learning how Pat’s particular home life, and not just the war, might have contributed to his pain.

It was at the time of the move to California, says Rina, that Pat started seeing a psychiatrist weekly. He avoided the VA, not wanting mental health treatment on his military record. So he sought out a community psychiatrist.

It made sense. American psychiatrists had urged soldiers to buck up and reclaim their stoic masculinity, so there was no use confiding in loved ones. Not to mention, after years of wartime propaganda, “many civilians thought of the war as some extended boy-scout summer adventure camp,” wrote historian Hans Pols. There was no framework for spouses and relatives to understand the suffering of World War II and Korean War veterans. (A high-ranking officer, Pat escaped active duty in Korea.)

At the same time, the popularity of psychiatry propelled the profession out of the mental hospital’s stigmatized confines and into the community via private outpatient offices. Thus whether depressed, “psychotic” or still suffering the woes of war (due to previous familial dysfunction, the doctors would say), men found their way onto the couch.

In the early 1960s, there was a good chance a person with anxious and depressive symptoms, seeking the help of a community-based psychiatrist, would be prescribed Elavil. While psychiatrists still relied heavily on psychoanalytic talk therapy and occasionally electric shock, the early 1960s saw the popularization of a new treatment tool for mental health: the drug.

Drugs first aimed to tackle schizophrenia. Then doctors noticed some helped depression. Elavil was the brand name of a new such antidepressant, the tricyclics. Many studies (often of dubious quality by today’s standards) showed the Elavil had a positive effect on the majority of patients, particularly those with “agitated or anxious depression.”

But mostly it was thanks to clever marketing, transnational deals, and the commercial powerhouse that was Merck and Co. Pharmaceutical that Elavil became the most widely-prescribed antidepressant in the world.

Pat was no exception to the trends in American psychiatry. Rina says she got a full-time teaching job to pay the $50-per-appointment bills and the cost of the Elavil pills the psychiatrist prescribed.

Add a sleepless, anxious husband to prevailing cultural attitudes bent on keeping you in the home, and the independent woman may have felt justifiably overwhelmed. Recent studies on spouses of veterans have found what’s called the “compassion trap”: excessive sacrifice to keep the family afloat at a time when there is the least amount of marital intimacy to draw upon for support.

What Vicki and Susan remember, though, are the fights.

Rina and Pat fought constantly. Susan remembers arguments over her father not handling money very well and getting caught up in ill-fated schemes. The first time Vicki learned that her father had been hospitalized for mental illness was during one of these fights. They remember once their mother threw some plates — something Rina contests. (She does concede that once, in an argument, she threw out all the lentil soup she’d made.) Pat would usually stay quite calm, then occasionally explode.

The Legacy Of Suffering

Pat died in 1974 from metastasized cancer that had riddled his insides. Doctors said he had gotten skin cancer in the South Pacific, and it had spread. Susan was 15 years old. In his last weeks, the handsome, broad-shouldered man shrunk down to a pale and underweight living corpse.

19 years later, I was born.

I’m not sure why I felt so compelled to understand the truth of my grandfather. Maybe it was because he functioned in my life as a picture book character from my childhood, popping up in my mind in brief flashes, but which I never could recall fully.

Now, having looked deeper, I am haunted by the battleground question of the 1950s psychiatrists: Was it the family or the war? Was there brokenness always there, to begin with, causing violence — or did the introduction of violence break something?

Why did my grandfather suffer?

Modern research into PTSD suggests that environment — war, family — and genetics both can have an effect. You can be primed to break down, even though it’s trauma that causes the breakdown. The exact relationship remains unclear. For instance, does having a genetic proclivity for depression increase the chances you’ll get PTSD? Or does getting depression alongside PTSD simply mean the environmental trauma was exceptionally strong?

“There is no single way for human beings to respond to the terrifying events of war,” wrote the historians Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely. There can be shell shock and PTSD and whatever variation my grandfather experienced. There can be arguments with the people you ostensibly love and a longing to conform to societal pressures. There can be pain — for soldiers, for people they return to, for descendants they’ll never meet.

I hope, with the context of the World War II veterans’ suffering, to have banished the madness from the corners of my family’s narrative. But I still don’t know my grandfather. The truth I went in looking for doesn’t exist. All I have are more brief flashes of the man that these three women that I love constructed in their minds.

So I let these grains of a life run through my fingertips and fall where my grandfather, ever circumspect, left them himself: on a beach somewhere in the South Pacific, where the pain and destruction on both sides were near unspeakable.

Instead, I turn to my mother, with her bright smile and fond memories and the resilience that only great suffering can bestow. My aunt, with her shelves of medical textbooks and her hard-won knowledge, hands raw from forging the life she wanted. My grandmother, an inhabitant of this globe for nearly a century, with her contradictions, her tangle of recollections, her unyielding fortitude.

In losing my grandfather, I gain kinship with their minds — and thus am inducted into a different kind of family legacy. I see not the man who preceded me but the truth that these women know: a broken story does not compel a broken life.