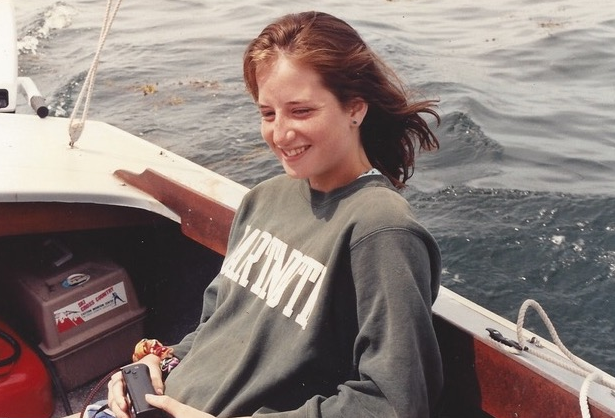

The author in 1991 at age 18.

After poring over the reports of Brett Kavanaugh’s sexual aggression at Yale, I can’t stop thinking about the frat-boys I knew in college. Preppy, athletic, and moneyed, they strolled across the Green like they owned the place, ball-caps on backwards, then bonded and binge-drank at basement ragers. We heard about the foul misogyny of their meetings, but they could do what they liked inside the enclave of their houses.

These privileged young men, raised in elite private schools, objectified women as a form of sport. But no one called them out on their actions when they were young, and they believed they were untouchable. This belief only magnified as they grew up, powerful in their respective careers. I should know — I’ve followed the former frat-boy who date-raped me at Dartmouth.

Said frat-boy is now an Ivy League success story, an attorney in the public eye, possessing power and wealth. Although I just finished a memoir on silence-breaking and have written his drunken violation as fiction and poetry, I never considered speaking his name until Dr. Ford and Deborah Ramirez bravely came forward.

For years I called it sexual coercion.

At Dartmouth we were both teenagers, a couple of kids who ran around the Homecoming bonfire and flirted at beer-fueled dorm parties. The shame of my story is that I liked this guy. Hungry for love, I wanted him to like me back, find me smart and pretty and cool. Our freshman winter we started hooking up— or “fooling around,” in the parlance of the era. On Valentine’s Day 1992 he gave me a copy of Gibran’s The Prophet, which seemed like a symbol of affection. A week later, on a Friday night, I waited up for him in my pajamas in my two-room double on the top floor of Woodward. I had a ski race the next morning and had to catch the van at 6:30 am, but still I waited— because I liked him, because he’d told me he might stop by. After midnight he lurched into my room, drunk from a party at an infamously debauched fraternity, the same house he’d rush later that year. We listened to The Doors and made obligatory conversation, then slid into another make-out session on the rug.

Here’s the catch— I wanted to fool around with him. I was sexually adventurous and attracted to the guy and game to do pretty much everything except actual intercourse. That night, when I saw how wasted he was (“stumbling drunk,” as Ford described Kavanaugh), I should have told him to take a rain-check. But I led him down the hall to my friend’s empty single, where we shed most of our clothes. When he asked if I was on the pill, I said no, then tried to distract him with oral sex. He rolled me on my back and shoved his erection into my panties, his breath beery and sour. “What are we doing?” he slurred. “Not this,” I answered. He kept trying to penetrate me. I said no and no and no again, my voice getting smaller and smaller until it morphed into a whisper inside my head. He was still trying, hard and heavy and undaunted. Eventually, I understood that he was not going to leave. I saw my choices and gave up, gave in, lay there silently and endured the excruciating pain of that sex. Afterwards I stood under a warm shower and tried to soothe my stinging groin. I felt visceral revulsion at the thought of his mouth. Before he left, he’d told me he’d vomited in the dorm bathroom just before knocking on my door.

You Might Also Like: 7 Ways To Protect Your Healing Heart When The News Is Full Of Sexual Assault

We barely spoke again for the rest of college. Filled with shame and confusion, I told several friends and counselors, but no one encouraged me to report the incident. Coercive and non-consensual sexual encounters were normalized at Dartmouth in the 90s. Drunken groping or worse… it was just what happened. By the time we were seniors, every woman had a rapey story or else a friend with a rapey story. And because I hadn’t screamed or pushed him off me, I believed my silent night existed in “a gray area” — a murky borderland between sex and rape. Society demands women be “good victims” who fight back, and I had not fought. I lit a candle at the Take Back the Night vigil on the Green but didn’t believe I deserved that ritual, not like the student who’d survived a vicious attack at knife-point in a city park. As an attempt at empowerment, I published a third-person account of my experience as “fiction” in the campus women’s newspaper, Spare Rib. When I return to that story now, it reads as sexual assault. But in 1992, no one raised any questions.

While the frat-boy went to law school and worked at top firms, I carried a residue of shame through the decades. No achievement erased it— not graduating Salutatorian from Dartmouth or going to Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. The first time I saw his name in the media, I burned with humiliation and rage. He had surely forgotten me, but I had not forgotten his transgression. After I became a mother of daughters, I longed to be a strong role model for them, raise my girls to speak louder and more clearly than I did. I began to interrogate the sexual culture we lived in and examine the costs of female silence in a memoir. In 2015, I was stunned when my therapist told me about the new policy of “yes means yes.” California had made “affirmative consent” the legal standard on college campuses, and as I read the details of the 2014 bill, I got chills: “Lack of protest or resistance does not mean consent, nor does silence mean consent.” I was hauled back into that silent dorm room at 18, my body on the bed braced against his thrusts.

For further validation, I reached out to Erin Murphy, a fellow Dartmouth ‘95 and Professor at NYU School of Law, to ask if the legal definition of consent had changed since 1992. '"There is no national definition of "consent,"' she told me in an email. When I wondered what happens when a verbal “no” changes to silence, she clarified.

“Historically, sexual assault laws only prohibited acts of penetration when the other person resisted — and often even verbal resistance was not considered enough. But in the past few decades, states have universally acknowledged that verbal refusals are enough to convey the absence of consent. And more recently, there is growing recognition that, in the context of something as intimate as sexual intercourse, consent means that a person is affirmatively willing, as opposed to not affirmatively resisting. In this context — often called “affirmative consent” — giving up, or passivity, is not enough to signal willingness, and so penetration in the absence of some sign that the other person welcomes that penetration would constitute a sexual offense.”

A sexual offense.

Professor Murphy’s words steeled my resolve, as did California law. The former “gray area” had crystallized into black and white. As I began writing this story, some people suggested I contact the former frat-boy first, a thought that made me recoil in fear and disgust. Why is the onus on women to reach out to our assaulters, either to seek private healing or gently educate them about their misconduct?

Women have the right to speak publicly, with legitimacy, about the men who violated our bodies when they were boys. It’s time to cut through the illusion of the Ivy League pedigree. To pull back the curtains of privilege and power and look inside these hallowed institutions — at the culture of entitlement that festers within. Galvanized by Ford’s and Ramirez’s courage, we can break the silence and shatter the myth of these impervious men.

And Mr. Ivy League, if you’re reading this, know that you caused harm. Your inebriated quest to get laid had lifelong impact for me, and I still flinch when I see your face in the news. But I’m setting down my shame, like an old coat that no longer fits. The shame is yours. Teach your sons to do better.