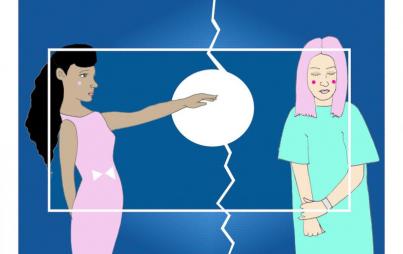

Less access to quality treatment and resources is deeply concerning given that those that are available already lack understanding about cultural identities and how mental health conditions affect minorities. (Image credit: Instagram/tothebonemovie)

Content Notice: Eating Disorders

When I was 16 years old and deep into my eating disorder, it was my dad who first thrust me into the reality of my situation. It was the middle of the night and I was standing in the kitchen picking chocolate chips from mint ice cream in an effort to save calories. Purging by taking multiple laxatives a day, running to burn off dinner, and tallying calories on a piece of paper in my dresser drawer often left me hungry and restless in the middle of the night.

“Sweetheart what are you doing?” he said. After that, my parents helped me find treatment.

Several years later, I would journey down a similar road, this time in the form of postpartum depression and anxiety. Before I went to bed, I would ask my husband if he thought I would wake up in the morning. Then, unable to sleep, I would sit on our living room sofa and stare out the windows, watching for movement in the darkness that would prove threatening to my family. Panic attacks led me to the emergency room twice. When doctors couldn’t give me the help I needed, my parents, siblings, and husband stepped in.

And still, when I was standing on the other side of both situations, I would worry:

“What about the people who don’t have what I had?” After all, I was white, had health insurance and a support system, and secured the financial means to pursue alternative treatments.

That same question crept in as I recently watched Netflix’s latest drama To The Bone, the story of Ellen, a white, 20-year-old woman who is struggling with a serious eating disorder. I watched as she entered yet another inpatient treatment center and her loving — even if they do sometimes dole out tough love and her parents are divorced — family stood by her. Frame after frame, I saw myself and grew angry for the people who were suffering and wouldn’t be able to identify, whether it was because of their race, support system, or lack of resources.

“The message that people living with eating disorders get from films like To the Bone is that to be loved, to be seen, to be cared for, you have to be thin enough to worry people, sick enough to pass out in public, and wealthy enough to go inpatient for your treatment,” says Hanna Brooks Olsen, a 30-year-old writer in Seattle who began recovery from an eating disorder in her early 20s. “Nothing else ‘counts.’ Unfortunately, it means marginalized folks — poor ones, those whose eating disorders are non-restrictive, people of color and so forth — often feel like their experiences don't qualify as an eating disorder.

“Treatment is very validating, and without it, a lot of folks feel like they just have to keep suffering alone.”

Dior Vargas, a NYC-based Latina feminist and mental health activist, agrees, adding that stigma, lack of resources, and poor healthcare policies are roadblocks that people affected by mental health conditions and eating disorders have to hurdle every day — something that’s not portrayed on screen.

"For all of the language and rhetoric about how eating disorders aren't really about thinness — they definitely are. I wanted, at my worst, to be so thin that I frightened people. I wanted to be so thin that people noticed. I wanted to be so thin that I looked like I could be as sick as I was.”

“The media representation of mental illness is very homogenous, which I think contributes to stigma in many ways,” says Vargas, 30, who created the People of Color and Mental Illness Photo Project to bring light to this subject. “Mental illness affects everyone in some way and it is doing a disservice to the experiences of people of color by showing only white people as those who deal with these conditions.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA), 20 million women and 10 million men in the United States suffer from a clinical eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, at some time in their lives. As researchers take a closer look at these populations, they have discovered that the prevalence of eating disorders amongst African-Americans, Asians, Latinos, and white people in the United States is pretty much equal. But the help is not.

“These movies that depict white, financially stable people represent only part of the community that suffers with eating disorders,” says Lisa Constantino, a licensed professional counselor and clinical manager at the Eating Recovery Center, in Denver, Colorado. “To The Bone does a good job of giving some psychoeducation about some of the functions of eating disorders for white, financially stable women, but does not depict the experience of marginalized communities and the way that the disorder may function in those communities.”

And the story for mental health conditions isn’t much different. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, approximately one in five adults in the United States — approximately 43.8 million — experience mental illness in a given year. Of those people, African Americans and Latino Americans each use mental health services at about one-half the rate of white Americans, and Asian Americans at about one-third the rate. The reason most frequently cited for not using mental health services? Service cost or lack of insurance coverage.

“Without financial and emotional support, recovery is incredibly difficult, if not nearly impossible,” says Kimberly Hershenson, a NYC-based therapist who has served on the board of NEDA. “Treatment entails intensive therapy and often inpatient or outpatient hospitalization. These treatments are not always covered by insurance, and if they are covered it may be limited to a certain small time frame. Recovery can take years and treatment for a few months will have little effect.”

Brooks, who during the most severe periods of her eating disorder was working 35 hours a week as a janitor and going to school full time, says movies like To The Bone are disappointing because they play into “so many old tropes and stereotypes” and the central character is one who audiences have seen time and time again.

“When I was living with my eating disorder at its worst, a character like Ellen would have been my idol,” says Brooks, recalling the hours she would spend “seething with envy” as she read message boards about the benefits of inpatient treatments. “She was beautiful, white, wealthy enough to get treatment, and thin enough to ‘look’ sick. And to be quite clear: For all of the language and rhetoric about how eating disorders aren't really about thinness — they definitely are. I wanted, at my worst, to be so thin that I frightened people. I wanted to be so thin that people noticed. I wanted to be so thin that I looked like I could be as sick as I was.”

Alyssa Jeffers, 26, of Hoboken NJ, agreed with Brooks, adding that her current battle with an eating disorder comes with people telling her she’s not thin enough to have an eating disorder.

“On screen, it’s basically thrown in your face that the thinner and sicker you look, the better chance of a treatment center accepting you into their program,” she says. “It’s incredibly dangerous for people like me who are silent sufferers that don’t ‘look’ like they have an eating disorder. It sends people like me the message that in order to be deemed ‘worthy for treatment’ you have to look as emaciated as possible.”

Brooks — who struggled to pay bills and sold plasma to buy groceries only to often be rejected because she was too anemic — says that, of course, what’s seen on the screen isn’t helped by what is currently unfolding for healthcare under the current administration.

“Reducing access to treatment may skew research and perpetuate the myriad stereotypes about eating disorders — what they look like, who gets them, and how old they are,” Brooks wrote in a recent article about how turning over the Affordable Care Act might affect treatment. “When people from marginalized groups — LGBTQ individuals (particularly trans youths), people of color, immigrants, and the very poor, to name a few — don’t have access to treatment, they can’t be counted.”

For Vargas, less access to quality treatment and resources is deeply concerning given that those that are available already lack understanding about cultural identities and how mental health conditions affect minorities.

“If someone doesn't get equitable treatment, then they are less likely to seek help again,” Vargas says. “I believe communities of color are constantly being robbed of their humanity by not being seen as capable of pain and by not receiving the care they deserve. There are policy and structural changes that need to happen in order for society to overcome that.”

Editor’s Note: July is National Minority Mental Health Month — learn more about the Human Right Campaign’s #NotACharacterFlaw campaign by visiting the site.