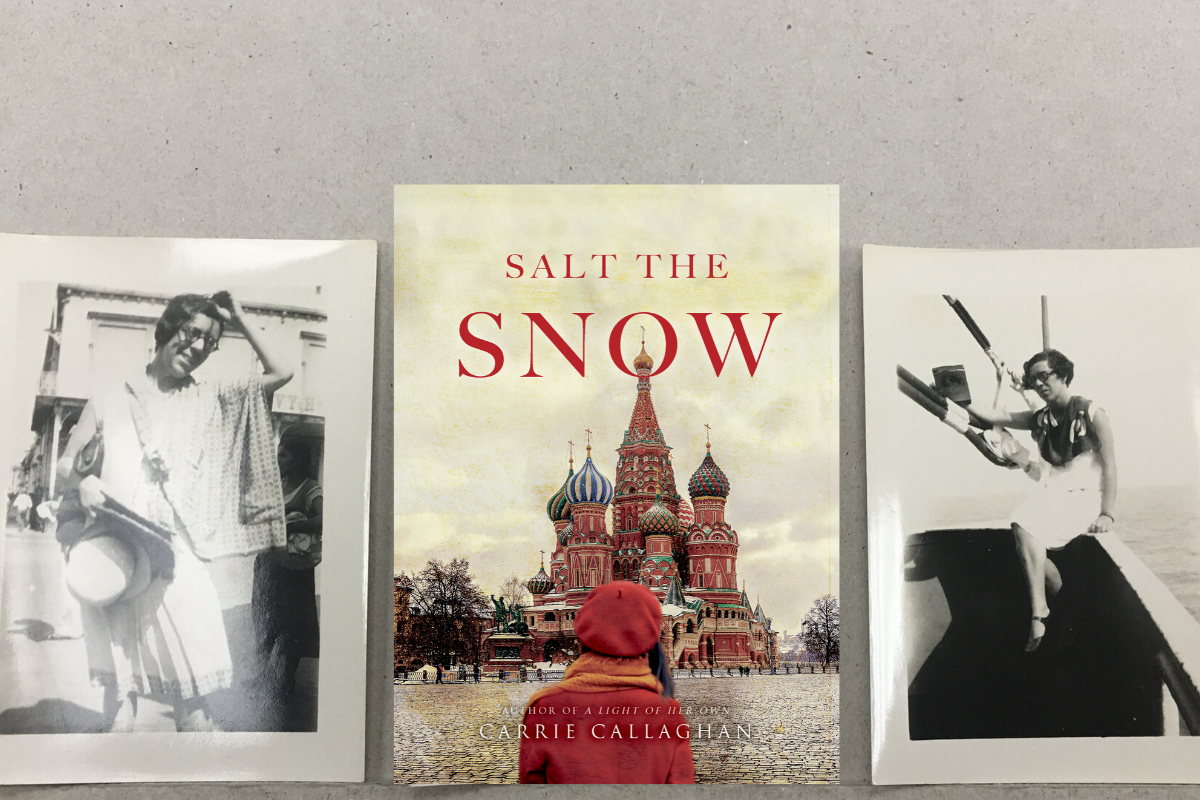

Image of book and Milly courtesy of Carrie Callaghan.

She had too many lovers.

Too many lovers, that is, for me to reasonably account for in a 300-page novel covering approximately six years of journalist Milly Bennett’s life. There was the hardened newspaperman, the married man, the other married man, the young Russian opera actor, the older Russian writer, the American socialist, his brother the communist, the famous geneticist, the volunteer warrior, and some I’ve forgotten or who didn’t merit a mention in Milly’s letters.

Milly was unabashedly sexy, with great legs and killer dance moves, though her friends politely noted she wasn’t exactly pretty. Her enemies were less kind. She traveled the world writing about murders, politics, and industrialization, but on each continent, she also fled a broken heart.

Because, although Milly was delightfully sexually liberated, and though she told herself all she wanted was a good “tumble,” her heart whimpered that she wanted more.

Reading Milly’s letters while researching my second novel, Salt the Snow, I wanted to reach back to 1931 and shake her.

“Milly,” I’d say. “You’re thirty-three years old. You’ve traveled the world, you’ve been married and divorced and had an abortion that you chose. Don’t you think you’re kind of awesome? And you should only be with men who think you’re awesome?”

That’s the tragedy of being interested in history: I can’t do anything but listen to Milly’s broken-hearted letters. But by virtue of the magic of being a historical novelist, I can imagine a way to shape Milly’s experience.

I can teach her, or at least the fictional her.

Historical fiction is never just about the past.

Novelists today writing about yesterday have a foot in both worlds, and we’re deeply concerned about how the past has shaped our present and how we can understand contemporary issues by seeing them through the comforting distance of the past. Historical novelists are bridges, building ephemeral structures that allow a meeting between the historical record and the questions we need answers to today.

So when I wrote about Milly’s week of sex in a Spanish hotel and the pleading letters she sent to her lover (which she sent before she got his “hey, thanks for the good time” note), I was reflecting the archive Milly left behind. But I was also shaping her story to reflect the still-pressing issue of how to know when you’re falling in love, or when you’re just someone’s fling.

Milly, I decided, needed to love herself before she could love any of her lovers.

This brave woman who was one of history’s first female correspondents to report while under fire, who protected her sources against heavy political pressure, who tried to tell the truth while having the courage to believe in the risky better future that the Soviet Union promised, this woman didn’t quite know how to love herself.

Self-love and self-care are terms we bandy about with ease these days, but how many of us really know what it means? How many of us can look at our flaws and our mistakes, acknowledge them, and forgive them? How many can recognize that it’s not selfish to expect respect, or to reject martyrdom because it’s really someone else’s attempt to manipulate us?

Milly Bennett had plenty of lovers, but it took her a long time to find love. Strangely, it was her gay (or bisexual) husband who first showed her the way, I think, when he found grace in the most forbidding of places.

Milly, as I wrote her at least, discovers her own stride. In doing so, she channels the moxie that contemporary humans are still hoping to find: the courage to believe in ourselves first.