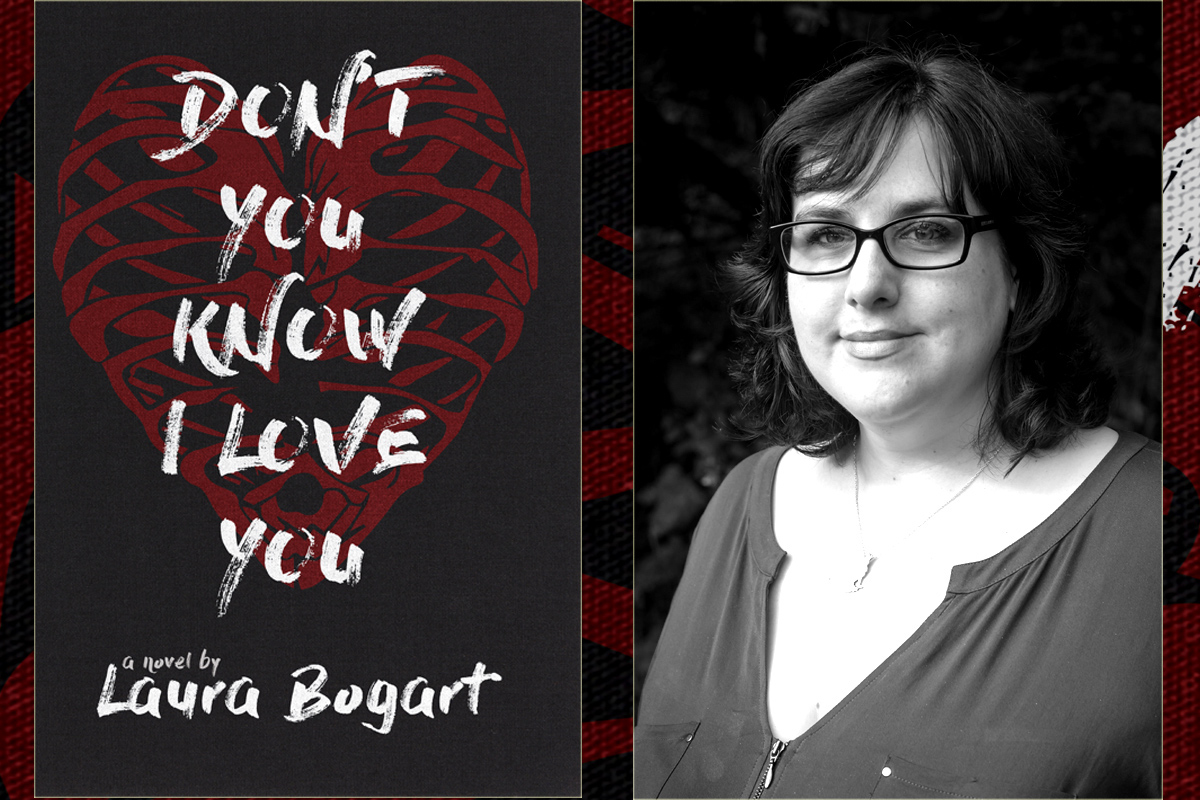

Laura Bogart's Don't You Know I Love You

Ravishly presents an excerpt from Laura Bogart's Don't You Know I Love You.

About the book: The last place Angelina Moltisanti ever wants to go is home. She barely escaped life under the roof, and the thumb, of her violent but charismatic father, Jack. Yet home is exactly where she ends up after an SUV plows into her car just weeks after she graduates from college, fracturing her wrist and her hopes to start a career as an artist.

Angelina finds herself smothered in a plaster cast, in Jack's obsessive urge to get her a giant accident settlement, in her mother Marie's desperation to have a second chance, and in her own stifled creativity - until she meets Janet, another young artist who inspires her to make the dynamic, unsettling work that tells the story of her scars, inside and out. But excavating this damage, as relations with her father become increasingly tense, will push Angelina into making a hard choice: will she embrace her father's all-consuming and empowering rage, or find another kind of strength?

Angelina shifted her hip to reposition the sketchbook balanced on her knees. The free fingers of her plastered hand grazed Janet’s bare thigh. The feeling was a long, slim needle that frayed apart the straw doll of her body.

They were seated on the wooden planks of the stage where, in two days, Janet and some of her friends would perform in a queer cabaret: burlesque, spoken word, and a film screening. The night before, Janet had invited her, via text, to come down to the “creative living space” (which was really just a warehouse that had been divvied into dorm-like studios, still over $700 dollars a month) to help with the set decoration.

When she arrived at the performance area—rows of fold-up chairs in front of a twenty-by-sixty-foot stage; cement walls, painted black—Janet greeted her with a hug just snug enough to give her hope.

Janet wore a shirt made from two tank tops sewn together, black under pink, and artfully frayed the edges. She’d stitched a design in the center of the chest, a horse skull with a unicorn horn. Silver thread with some glued glitter. Angelina chuckled, shyly pinched the fray along Janet’s hip and twisted it between her fingers. Janet said she’d thought Angelina might like it, “what with the bones and all.”

Angelina thought to ask about an exchange, a drawing for a T-shirt. But when she looked up on stage, she could see Janet had already given T-shirts to two of her friends. Not skulls and bones, but similarly unique: a bunny with butterfly wings and a cat with antlers. The girl in the bunny shirt was Maxine, a burlesque dancer with a sweet, shirt-stretching little belly and Bettie Page bangs. The girl in the cat shirt was one of the poets, Frankie.

The three of them had been puzzling over how to paint a pair of set pieces—“steampunk clouds; one a man’s face with a monocle made out of the clock gear, and the other one a woman’s face with copper wires for eyelashes”—and how they’d get those pieces to come together as the backdrop, then pull apart to sit offstage so a short film could screen on a large piece of blackout cloth nailed to the back wall. Angelina suggested they lay down a track like for a walk-in shower; even at ten feet by twelve, the plywood sheets they’d bought for the clouds were thin enough to be adequately supported.

“I told them you and your dad are two Sicilians working in construction who actually work in construction,” Janet explained.

“I don’t work for my dad,” Angelina said, holding the hair trigger in her tone.

“Whenever my mother tries to give me ‘career advice,’ she tells me to network,” Frankie said. “Anything that takes the brown-nosing out of the occasion is most welcome.”

“You just have to brown-nose the director,” Janet said. “But at least the director isn’t wearing a suit.”

“Oh darling, I’m going to be the director,” Frankie replied.

So, this is a group of friends.

Angelina felt like she’d spent the last four, almost five years confined near the windowsill of a tiny, empty room, where she’d only experienced the change of seasons by putting her hand on the glass, marking the heat or chill.

She knelt in front of her sketchbook and told Janet to start painting the plywood a “very light blue—cut it whiter than you’re comfortable with, if you have to” while she started on the design. When she shook her right hand to loosen it, Janet took hold of it. She lifted Angelina’s fingers, took them between hers, and twisted them gently, as if rolling cigarettes. She gave each one a soft tug. Popped knuckles teased relief before setting in a familiar stiffness.

They worked in tandem putting the basecoat down. Afterward, Janet worked on the costumes and Angelina painted the faces on the wooden planks. Janet sat on the edge of the stage with petticoats she had to let out, a pair of red hoodies that needed sets of black angels’ wings sewn along the shoulders, and a bra and hot shorts she was stitching over with metallic sequins. She pulled a thin blue moleskin from her back pocket, set it on the floor, and squinted down at the open pages. Angelina smiled. Janet had sketched tiny skeletons and built her figures around them. The figures weren’t quite in proportion; still, they were more solid and accurate than anything Janet had drawn before.

On their third date, hanging out at the Cylburn Arboretum—gardens of bright orange hibiscuses that Janet said looked like “tongues of fire;” so many rows of roses, the delicate white teacup roses, the solemn blue-gray roses, the red roses so hot in color and so thickly clustered that they seemed to throb on the bush; and the peonies, relaxing their obscene plushness in a feathery spread of pink—Angelina showed Janet how to draw figures. They sat on the steps of the old mansion house turned information center, the sketchbook open across Angelina’s knees.

“I’m simultaneously jealous of, and aroused by, your talent,” Janet said, watching her sketch the first outlines. She leaned into Angelina, the scent of her perfume—an ylang ylang essential oil that was a core element in the Chanel No. 5 she couldn’t afford yet—supplanting the flowers and the night air.

“Well, show me what you’ve got.”

Angelina had become accustomed to being the nervous one—the one who had less to offer, and not only knew it, but knew that the girl she was with knew it too.

Now, as Janet took the pad from her and babbled about a lack of formal training and studying from magazines and those dummy models from the art store, all the “ums” and “you knows” were like fizzy little bubbles that rolled over Angelina’s skin, delectably ticklish. Janet knew exactly what she wanted the clothes to look like, but her figures were skewed, the arms too short and the torsos too long.

“What you need to understand is that the body is in rhythm with itself,” she said. At Janet’s blank look, Angelina stood up, held her arms straight at her sides. “See, my wrists are flush with my hips and my elbows pretty much align with my waist.”

Janet leaned back on the stair, pressing her weight into her elbows. She looked at Angelina in the same way Angelina had looked at many models, lingering yet clinical—then that look at became a look over, a soft leer that held onto her hips, her belly, and her breasts. She waited to hear that siren wail inside her head, urging her to sit down. But Angelina heard only that recent memory of Janet murmuring that she liked these flowers like she liked her women, plush and pretty, as she inhaled the scent from one of the fluffier peonies, as she stroked her fingers through the petals.

On the drive back to Janet’s place, Janet brought up the burlesque show and asked Angelina if she’d be interested in helping with the set. Angelina agreed at once to do a giant set of panels as stage decorations. She did not say that she’d never ever attempted anything like that scale before.