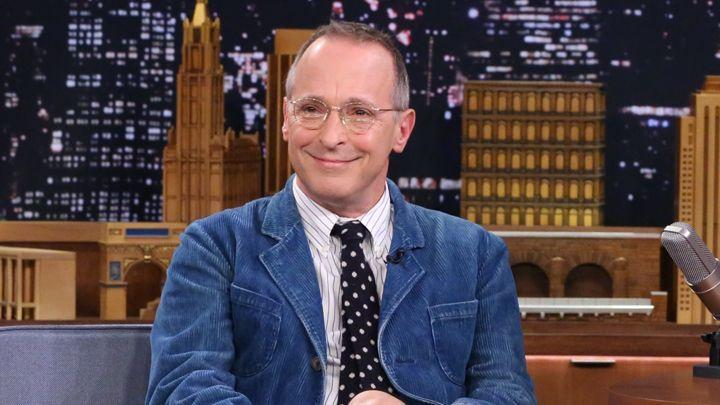

What’s in a name? I don’t really know. Sometimes nothing. Sometimes everything. Image: NBC.

“You can go anywhere with a name like Huckleberry Hartley.”

My child, the one who would never be born, was named by David Sedaris.

He was one of my favorite authors. He was holding an open forum after a reading, and I stood nervously on the lawn in front of the bookstore milling through my options. I could have asked him anything. Surely, as a writer, there were many things I would love to pick his brain about, but in my obsessive fandom I forgot all of that.

I asked him what to name my unborn child.

“What's your last name?” he asked.

“Hartley,” I replied.

Without missing a beat, he said, “Huckleberry.” He was very matter-of-fact — as if it were the only logical choice, the name I surely should have thought of already. “You can go anywhere with a name like Huckleberry Hartley.”

It caught me off-guard, though I’m not sure what exactly I was expecting. He went on to suggest naming my child “Congresswoman” if it turned out to be a girl, but I had a feeling that my child was a boy. My Huckleberry.

“Huckleberry” was soft and kind. It was the sort of name I could imagine myself whispering to my sweet baby as I implored him to stay little forever.

Sedaris said he often had folks who asked him to name their babies, and that he could always tell they weren't going to honor his wishes. I must have made a face, probably because I was still feeling a bit star-struck talking to him, and he thought he had me all figured out.

Just you wait, I thought.

That night, as I drove home, I imagined how I would track him down to send him a birth announcement, dubbing him honorary godfather of Huckleberry Hartley.

It wasn’t the name I would have picked — not originally, at least — but as days turned into weeks, it grew on me. I even talked my husband into it, telling him we could call him “Huck” for short. Huck was a nice strong name. You don’t want to mess with a man named Huck. “Huckleberry” was soft and kind. It was the sort of name I could imagine myself whispering to my sweet baby as I implored him to stay forever.

As I began to tell friends that I was pregnant, I told them the origin story of his name. I thought about how I would decorate his room with a line of Sedaris' books, all signed, as a reminder of his namesake. I (boldly) dreamt of my birth announcement being answered with a handwritten letter, filled with Sedaris' signature wit and sarcasm, that would sit amongst Huck’s baby photos and memorabilia.

That dream and so many others went up in smoke the day I saw my baby frozen on the ultrasound screen — no heartbeat, no movement.

There was no more talk of Huckleberry, or of a baby at all.

There were decisions that needed to be made. Appointments to be scheduled. Medications to be filled. A whole world of hope and joy suddenly overshadowed by a much more macabre future.

Though I had told many people about Huckleberry, no one mentioned him by name after my miscarriage.

The OBGYN who performed my D&C wouldn’t make reference to me losing a child or a baby or my Huckleberry. He told me it was just like an abortion, talked about fetal tissues. I clung to that name as I went through the most painful procedure I can imagine, both physically and emotionally.

The pain was worse because of it. It wasn’t “just like an abortion.” It was like losing a baby whose future I had imagined constantly for months on end. He had a name, a story, a future — and it was all ending right then and there.

“Does it really hurt that badly?” the OBGYN asked, frustrated with my wailing.

You’re goddamn right it does, I thought.

“It’s mostly emotional pain,” I said through tears. I resented him for asking. I wish he had just done his job.

Though I had told many people about Huckleberry, no one mentioned him by name after my miscarriage. At times I wished I had no name for him, no dreams, no hopes — but that’s an impossible request, isn’t it? What’s in a name? I don’t really know. Sometimes nothing. Sometimes everything. It all depended on what my grief decided to serve me on any given day.

Over time though, as I moved through my grief, I felt grateful that I was able to put a name to the child I would never hold. Having a name for my miscarried baby made my grief feel more legitimate; the life lost, more real. My miscarriage is not simply an event in my mind. I miscarried a child — this child, with this particular name, one who could never be replaced even as I moved forward with my life.

Even as I gave birth to another child, Huckleberry stayed, frozen in time, rooted deep in my heart. His name remains, written in the dark, soft places in my soul. A name I could never forget, even if I tried.