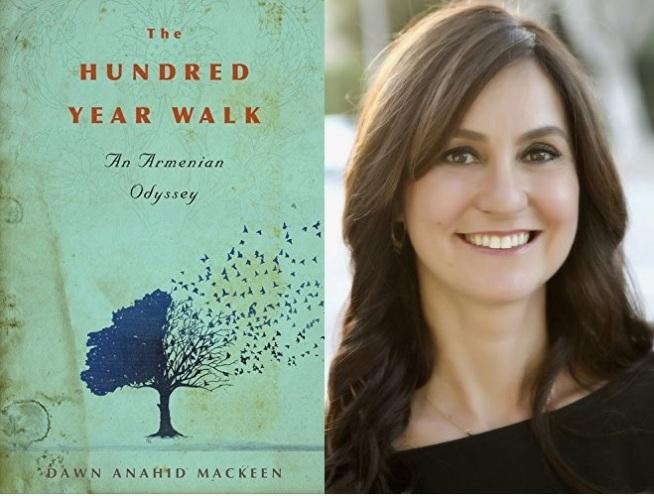

Dawn MacKeen digs up a hidden past in her newest book.

"He was a survivor. I hadn’t thought of him — or anyone else who endured a genocide — as having a personality, as being funny and knocking back stiff drinks with pals."

Not everyone has tried to talk to the dead. If you have, it's because you gave up on the profound loneliness of knowing that only the dead can answer a question. It is not a prayer, but a surrender.

Guide me spirits, who know what I cannot know.

Dawn MacKeen's book, The Hundred Year Walk: An Armenian Odyssey is a conversation with the dead, her Armenian grandfather, and the ghosts of the Armenian genocide. It marks the 100-year anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, when 1.5 million Armenians were sent to their deaths, while Europe and the United States sat idly by and did nothing to intervene on the Armenians' behalf.

When talking to MacKeen about her book and the connections it has to modern-day conflict, she likens the Armenian Genocide to what is happening in Syria. "Since the (Syrian) war has broken out, there have been many times that I had to assess the manuscript as it was closing. There's a church that I visited in the book in Der Zor, a memorial to the Armenian Genocide, and that place has been bombed and blown up on purpose, since the conflict began. So that is a place where there is a repository of genocide victims that were found in that area, so if you talk about, is history repeating itself? Yes! Even the memorial for the genocide victims, it's blown up, it's no longer there."

As the death rate in Syria rises and the bodies of refugees float to our shores, MacKeen is right in her assertion that history is repeating itself. Can we prevent the mass decimation of a people, or will we once again be caught in a game of global politics with blood on our hands?

MacKeen almost gave up on writing her grandfather's story. She had experienced so many starts and stops along the way, and when she discovered that several years of her grandfather's journals were missing, she decided that the only way that she could continue writing The Hundred Year Walk was if all of her grandfather's journals were found. In a fight that she had with her mother about stopping her work on the book, MacKeen said, “I cannot help you unless you raise your father from the dead.”

The next day, after searching tirelessly through her library, her mother found one of father's missing journals. After that, her mother called a sibling to look through all of their belongings, and another journal was uncovered. At this point, MacKeen had journals documenting her grandfather's experiences before, during, and after the Armenian Genocide.

Her grandfather had risen from the dead. He wanted his story to be told after all.

Writing The Hundred Year Walk was its own type of surrender for MacKeen, who spent 10 years researching the book and, with the help of her family, translating her grandfather's journals. Each provided his firsthand accounts of the horrors he witnessed during the Armenian Genocide. Ultimately, MacKeen found herself physically retracing her grandfather's steps, which led to his eventual escape of the Armenian Genocide. He had to walk by foot through harsh terrain, he crossed a dessert, and went into hiding in Syria in order to survive.

MacKeen revisited all of the sites mentioned in his journal in order to understand what this man went through, and to understand the grief that so many Armenians still carry.

It was a story that was difficult to write, as those who survived the genocide had already died by the time MacKeen began writing her story. Add to this the difficulty of traveling through Turkey and Syria while searching for answers that the government actively denies, and you have the makings of madness for a writer.

But MacKeen persisted. Her background as an international reporter helped her research, ask questions, interview those that she met on her travels, and get more of a composite picture of who her grandfather was. MacKeen wanted to know more about him; more than the fact that he had survived. In writing The Hundred Year Walk, she realized, "Somehow, I had reduced him (her grandfather) to one dimension: He was a survivor. I hadn’t thought of him — or anyone else who endured a genocide — as having a personality, as being funny and knocking back stiff drinks with pals. That’s what a holocaust does — it erases."

MacKeen's new book gives her grandfather's story a life. It takes back the narrative of genocide and asks, Who were the people who died? Who were the people who survived? What were their hopes, what were their lives like before and after the genocide? What can we learn from this?

The Hundred Year Walk is an offering that speaks to the Armenian Genocide, what is happening in modern-day Syria, and the silencing of suffering all around the globe. The hope is that we will listen to our ghosts, we will listen to MacKeen's story, and we will be inspired to stop history from repeating itself.