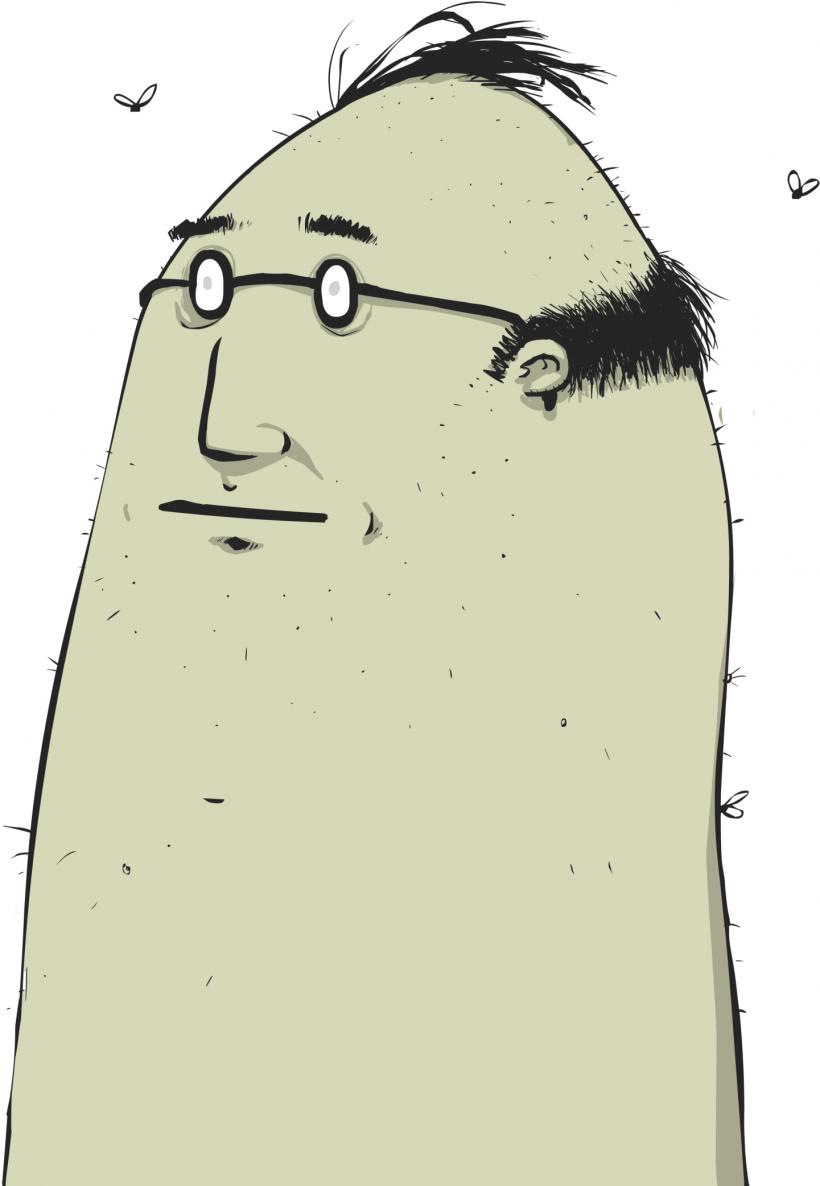

On a quiet Monday night in Phoenix, Harriet met Death for the first time. He wasn't particularly imposing, she thought at first, no hood or staff; he was short, rumpled, and balding, in an ill-fitting pair of khakis and a blue striped shirt. He looked like an IT consultant or a bewildered dad at a PTA meeting. The only way Harriet knew her opponent was that the room turned black, and he was oddly floating towards her.

"Hello?" she asked shakily, sitting up in bed. Her copy of Ladies' Home Journal slid down to the floor, queasily resting on a pair of house slippers. "Can I help you?"

"Eh," he said nervously, fumbling with a rumpled legal pad. "Ahem. So, I think I have the right person. Harriet Simpson. . . 52 years old. . . bank manager by trade. . .763 Altoona Lane?"

She considered denying it, but realized that if the man in front of her was floating, he probably knew more than she did. "Yeah," she said after a minute. "That's me."

The specter uncomfortably adjusted his thick wire-framed glasses. "Well, Harriet, I've got you down on this list unfortunately. I think we both know what's about to take place here. Looks like at 9:55 tonight, you're going to have a brain aneurysm. Fatal, I'm afraid. Your husband is going to find you at. . ." he scrolled apologetically through his legal pad- "ooooh. Not til tomorrow morning. Guess the Ambien really knocked him out. Should be careful with that stuff."

Harriet fleetingly thought of her husband, conked out downstairs on the recliner, before her thoughts turned to her own life.

"Please," she begged Death, tossing aside the paisley comforter and prostrating herself on the matching paisley sham set. Her thighs quaked in fear; a lone tear washed mascara down her cheeks. "Please don't kill me now. I have so much to live for-"

"Look," he explained reluctantly, "I don't give the orders-"

"-but you carry them out," Harriet sobbed. "Please, please don't carry this out."

Death grunted and flipped his notepad impatiently. "Well, according to protocol, someone has to die tonight."

"But why not someone else?" Harriet howled.

Death raised his thin eyebrows in curiosity. "You'd rather have someone else take your place?"

Harriet nodded tearfully.

"Well, there's some moral ramifications to that- essentially you're killing someone else so that you can- eh, anyway, alright. Shouldn't be talking about morals, should I?" He pulled out a Bic pen and rummaged through his list. "Look, I can cut you a temporary deal. Give me a name and I'll leave you alone for the night."

"Sandy Walsh," Harriet choked. Sandy was the sour, ancient neighbor who reported her to the Homeowners' Association after Harriet had painted her flowerboxes a different shade of blue. She'd had it in for Harriet since the Simpsons had moved to Altoona Lane eight years ago. "Now will you leave me alone?"

"For the night," Death said simply, ominously. "But I'll be back."

The room lightened. Trembling, Harriet picked up her copy of Ladies' Home Journal from the floor. There was a good lemon merengue pie recipe.

Unfortunately, it wasn't a dream. Harriet was roused from her slumber the next morning by her husband Thom, equally weary from an Ambien coma. He shook her awake at six, half an hour before the coffee timer. "What?" she grumbled into her pillow.

"There's an ambulance down the street. I think something happened to one of the Walshes."

"Good," she muttered, still half-asleep. And, then- "What?"

She hurriedly threw on a bathrobe and slippers, raced down the stairs, and wrenched open the front door. Two houses down, in the blinking chaos of emergency sirens and lights, she saw the grizzled, crabby corpse of Sandy Walsh strapped into a stretcher and loaded in the back of the ambulance. "Huh," she said, dazed, and turned back into the house. The coffee wouldn't be ready for another half-hour.

"Strange," her husband remarked an hour later, as they sat in the kitchen eating a breakfast of bagels and cream cheese. "I knew she was old, but I always thought Sandy was in good health."

In a rare moment for her, Harriet had nothing to say.

At first Harriet used her new companion to gently shed the people in her life that she found obnoxious. Beverly from book club who once insinuated that Sandy hadn't actually read Tuesdays with Morrie. The chirpy blond twenty-eight-year-old from Human Resources who wore tantalizingly high heels to accentuate her perfect calves. One of Thom's old college friends who got annoyingly drunk at Christmas parties. She was careful not to accumulate too many deaths in one place, neatly spreading them into categories- work, neighborhood, family- like sorting laundry.

Thom didn't really notice anything until after the death of his old frat buddy. After the funeral, as they soberly drove home in Harriet's 2007 Corolla, Thom rested his head against the window and asked, "Haven't there been a lot of deaths this year?"

"Not really," Harriet said flippantly, her steely eyes focused on the road.

"There have been. Who was that girl from your office? The one from HR who ran marathons or something?"

"Long-distance running can provoke heart problems," Harriet countered.

"I don't know," Thom sighed. "Maybe it's just me. Maybe we're getting old." He

leaned over to kiss his wife on her powdery cheek. "I just don't want to see you die."

"You won't," she said, and she meant it.

One night Death came to her and she had no more people in her life that she disliked- only a collection of scared family, friends, and coworkers who were dimly aware that a great darkness was sweeping through Phoenix with no end in sight.

"Can I make up a name?" she begged her tormenter in the gloom.

"I don't think so, but lemme check. . ." and out came the yellow legal pad, again. "Nope. Sorry. It's gotta be someone that you know."

"What if I don't give you a name?"

"I think we both know the answer to that," he said wearily.

Her eyes clenched shut, she whispered a name: "Bill Martinez."

The next day at the office Bill wasn't there, of course, and Harriet spent the entire day silently knowing in her chest that Bill was dead. The call came around 3:30 from Bill's anguished wife about his car accident. Harriet sunk deeper into her swivel chair as she heard her boss sobbing into his coffee mug. She'd liked Bill, he was a nice guy, maybe a little too enthusiastic about the Arizona Diamondbacks but you couldn't fault him for it since they did win the World Series a couple years back. His two sons were six and ten. They would go to Diamondbacks games on their own now.

The guilt began to accumulate along with the death notices. Her heart sank with every name, every funeral invitation. She started drinking red wine before bed. One night she popped one of Thom's Ambien, but Death shook her awake in her stupefied state. His hands were surprisingly warm for a ghost's. She mumbled a name and collapsed back into a restless sleep.

Gradually the people in Harriet's life started to empty out. The office was quiet, somber; fewer loafers and pumps walked the hushed carpet. Her book club was gone now, not that she'd been crazy about any of them anyway, but she missed the pot luck dinners after book discussion. Her neighborhood lay still and bare, the only sound from Thom's television shows in the den downstairs.

"Where did everyone go?" the mailman asked suspiciously, and that night she slipped Death his name.

She began stress-eating, the only response she could muster. One night she baked a lemon merengue pie and ate it all, with Thom watching frightened from the kitchen. Another night, after sentencing a favorite cousin to his fate in a train collision, she gobbled an entire lasagna with her bare hands. She could almost hear the shriek of steel wheels as she shoveled handfuls of pasta into her mouth.

A regular doctor checkup showed that her blood pressure was sky-high. The physician, a rail-thin man with angular cheekbones, sternly told her to follow a low-calorie diet. Heavy on the fruits and vegetables and limit the carbohydrates, ma'am. That night, as she spooned chocolate pudding into her desperate mouth, she didn't feel the slighest inkling of regret. "Dr. Evans, please." It was the first night she'd slept soundly in a while.

Finally the night came when she and Thom were alone in the world, because nights always come, regardless of whether they should or not. She cooked him his favorite dinner of spaghetti and homemade meat sauce with fresh shredded parmesan cheese, then laid it out for him on the kitchen table.

"What's this for?" he asked, pleased and bewildered. "Is it a special event?"

It was, but Harriet had no answer. She kissed him on the forehead, tears streaming down cheeks rubbery with cracked foundation. She silently turned and walked upstairs to the bedroom, where she slurped down a bottle of pinot noir beneath the covers and waited for her spectral companion.

Death appeared right on schedule in his slightly crinkled shirt, rubbing at his scuffed eyeglasses. "Let's see," he said briskly, flipping through the legal pad. "It looks like you've got only one sustainable option. Oooh. Apologies about that one. Guess he took a few too many Ambien. That stuff can be lethal."

"No," Harriet sobbed quietly, "please, no-"

And then Death was gone, leaving Thom cold and still in the armchair.

The next day Harriet couldn't move from the bed. She watched the dim winter sun stream through the blinds, aware that it was the last sunrise she'd ever see. Downstairs the TV still cackled with cartoons and game shows from where Thom had passed silently, the Ambien ceasing his warm breath. She lay frozen stiff in her own terror. Church sermons, existential writings, and documentaries on Zen Buddhism had never quelled her fear of death. Tonight she would face the yawning black hole of eternity from which no one returned.

She thought briefly of all the creatures that had passed before her, stretching back over the eons. Every organism that had been born, reproduced, and died. If there was a Heaven or an afterlife, it was populated by the floating ghosts of all species: rabbits, termites, tyrannosaurs. The simple fact that life eventually ended was too much for her to handle. But every living being had faced it before. Now it was Harriet's turn.

That night, the room turned black for the last time.

"Well," Death said plainly, "I've enjoyed our time together, and I'd like to thank you once again. I regret to inform you that there's only one name left, and that's-"

"Yours," Harriet said softly.

"Yes, I'm afraid your name is the last-"

"No," she breathed, suddenly hopeful. "Your name. Death."

Death balked suddenly, his plump cheeks paling to a ghostly white. For the first time he looked actually like a Halloween depiction. He frantically scrolled through his legal notepad, and Harriet felt guiltily foolish that she hadn't thought of this earlier. Bill from the office, her favorite cousin, and Thom had all suffered at her stupidity.

"Well," Death sputtered, "I don't know if I'm permitted to do this, I'd have to check with another division, there's really no precedent-"

"Death," Harriet said firmly, sitting up in the bed and clenching her jaw at the specter. "I'm giving you your own name."

"You can't do that!" the ghost wailed. "That's- not- fair. . ."

In front of her, Death's skin began turning a mottled shade of blue. The creature howled as its mouth contorted and its eyes rolled back in its head. Its body began to twist and fade into a shivering wisp. The rumpled checkered shirt began to disintegrate, along with the khakis and brown loafers. Finally nothing was left of Harriet's nighmare except a notepad, a ballpoint pen, and a pair of glasses.

She picked up the legal pad and pen, and began to contemplate her immortality.