My mother-in-law, Lydia Martinez Brown, left Cuba as a little girl in the late 1940s. She visited again briefly in 1958, the year before "the triumph of the Revolution" (as young Cubanos like to say), but returned to the States abruptly after a small bomb went off in a Havana theater where she'd been watching a film with friends.

In 1996, Lydia went back to Cuba. She was so haunted by the despair she witnessed in the years since she'd been away that I urged her to sit down with me with a tape recorder and talk about her experiences. She did.

In the wake of the recent U.S. travel restrictions to Cuba being lifted, Lydia's story reflects the mixed feelings shared by many Cuban émigrés when faced with the dilemma of returning to their former homeland, even for a visit. It also offers an up-close-and-personal glimpse at a previously-closed country.

The following is an excerpt from our interview.

My half-sister Emma and I used to make a sweet confection from tamarind pulp and sugar. We molded the dough into the shape of little hearts and sold the candies on the street to make extra money.

I took care of things at home while my mother sold cosmetics in the country. I cooked. I cleaned. I sent three children, plus myself, off to school each day. Then suddenly, there I was, on an airplane with my father, flying to America. I guess my mother thought she was giving me a better life. (She and my father had long split up and moved on. He had married and my mother had a boyfriend who didn't like me.)

The truth is my mother chose a man over me.

It was December. I wore a plaid wool dress that itched the entire flight. (Papi had forgotten to buy me a slip.) His new Cuban wife Rachel was waiting for us at Idlewild Airport. That's what JFK was called back then. She had a warm coat for me and seemed nice.

I spoke not a word of English, and in those days, few people in Brooklyn spoke Spanish. But everyone was kind to me, especially in school. I was skinny and small for my age. I should have been in the seventh grade but they put me in the sixth because of the language barrier. I was perpetually embarrassed; I couldn't even tell the teacher when I needed to go to the bathroom. But we used a kind of sign language until I could speak English.

I was a fast learner.

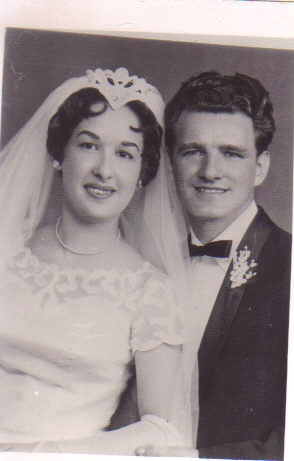

Eight years later, in 1957, I met a handsome man on the Fifth Avenue bus. I didn't care that Billy was on his way to the unemployment office downtown. I liked his bright blue eyes. I told my girlfriend Dottie, "That's the man I'm going to marry." Dottie said that Billy Brown never dated Spanish girls. Not only did we start dating, but we were married just three years later.

Billy and I had two children and eventually bought an old house in Park Slope. We both worked hard. I sewed buttonholes in a sweatshop, acted as a crossing guard and a gift-wrapper at Abraham & Straus during the holiday season. Then I became a bilingual teacher's aide in the New York City public school system I was good at what I did, I think, because I could understand what these children were feeling. Not so long ago, I had been in their shoes.

It wasn't that I forgot my old life in Cuba, but it seemed so very far away in the past. In 1970, I sponsored Emma (my half-sister) and her family, and brought them to Brooklyn to live with us until they got settled.

Emma and I kept in touch with our large Cuban family. They told us that our mother needed glasses, that our mother needed food. We sent money when we could. In 1996, my mother was 86 years old and ill; she wanted to see me and Emma before she died. There was no way I could avoid a trip back this time.

I applied for a special VISA, one which was given for medical reasons—to visit the sick, the dying. One which put $125 into Fidel's pocket. Emma had to pay $275 for a Cuban passport because she wasn't a US citizen. She and I arranged flights from Florida, where we both now lived. (After we retired, we couldn't take the New York winters anymore and moved to a warmer climate—maybe it reminded us of the place of our childhood.) Our suitcases were filled with soap, toilet paper and 65 pounds of flea market clothing to give away. (We heard that if you brought new clothes, your family would only sell them.) In my pierced ears, I wore tiny gold balls. I would return a week later with empty holes.

Waiting for us at the Havana airport was my mother with a handful of relatives. She was so thin and frail that she felt like a bag of bones when I hugged her. Emma had called ahead and told our cousins to get a turkey since it was the day after Thanksgiving. It was the end of the month and rations were low but somehow they managed to find one. We arrived to a meal of roasted turkey with nothing else. No rice, no potatoes, no vegetables. Ten minutes after we ate it, the turkey mysteriously disappeared.

Someone had taken the carcass to make soup.

My mother was fortunate because she lived in a part of Havana called Playa Marianao. Because many government officials and doctors also lived there, they always had water and electricity. But her top floor apartment didn't even have a real roof. Instead, it was covered with corrugated plastic sheeting. I couldn't imagine what happened when it rained. But her 1940s refrigerator worked well. She stored what little canned goods she had in a bottom dresser drawer; locked, even though she lived with family. No one was to be trusted when they were hungry. Emma and I slept with our money around our necks in travel wallets. We took the toilet paper out of the bathroom when we went to sleep at night because we knew it wouldn't be there when we got up.

But we soon got used to this kind of behavior. People would constantly take things and then disappear into the shadows like rats. It was a mentality I couldn't comprehend because in the U.S., you could buy everything you needed, even things you didn't. At first, the Cubans seemed greedy, but how can you call people greedy when they had nothing?

Cuba's dollar stores were always well stocked, though. They were called "dollar stores" not because everything cost a dollar but because you paid with American dollars. They sold TVs, food, furniture. If you had American dollars, you could buy just about anything. A pound box of macaroni cost three times what it did in Publix. A tiny jar of mayonnaise which sold for 89 cents in the States was $2.89. One morning, I woke up to find my nephew's girlfriend spreading mayo on crackers and eating it like caviar. She finished the whole jar in one sitting.

This was a different type of poverty than what I'd experienced as a child. Now I saw no hope, no ambition. It was as if people knew things weren't going to get better, so they didn't even try. You could almost feel their depression in the air. One of my nieces was a teacher but refused to work. "Why kill myself for 120 pesos (about six dollars) and a bottle of milk for the baby?" she asked me.

While I was visiting, my nephew got a good job making chocolate. The people who recommended him warned, "Whatever you do, don't steal." Three days later, he was fired when they found chocolate stuffed into his pockets.

Young Cubans spoke in a slang I couldn't understand. Was it some kind of revolt, this secret language? When I asked them to speak real Spanish, reluctantly they did. I also found it odd that no one mentioned Castro. The only time I heard his name was during an argument. My niece said, "People here have no cojones! That's what's wrong with Cuba. No one has the cojones to get rid of Fidel!"

I did what little sightseeing I could. Whenever I tried to go anywhere, 20 people wanted to come along with me. I managed to visit the cathedral and the capital, which was modeled after the U.S. capitol. It made me even more homesick.

The beautiful colonial buildings I remembered as a girl were still standing, but crumbling. Most houses were falling apart on the outside but nicely maintained on the inside. This was because you didn't want anyone to know what you had—they might try to steal it from you. Because of the U.S. embargo, it was also difficult to get materials like cement and paint to make repairs. Cuba had to rely on imports from countries like Russia and this limited their resources. When relatives wired money to their families, the Cuban government pocketed twenty from every hundred dollars sent. Fidel was even taking from the poor.

Lines for the busses often stretched a block long and they packed you in tight, like on Japanese bullet trains. To avoid the crowds, I hired a friend of the family to drive me around in his '52 Chevy. Rolando was part tour guide, part bodyguard. For all of the poverty, there weren't many beggars. But I was swarmed when I mistakenly took out an American dollar instead of a Cuban peso to pay for something.

They thought I was a rich American. Maybe I was.

I tried to keep a safe emotional distance from my mother, but it wasn't working out too well. I still had a strong resentment for her. I was extremely angry with her, and even after

almost 50 years, I couldn't forgive her. The day before I left, my dead brother's wife said to me, "You're lucky your mother sent you away. You should be grateful."

At that point, I snapped. A week of sleepless nights had taken their toll on me. A week of living with the desperate and the hopeless had sapped my strength. I had lost more than ten pounds in seven days. I had swollen glands and was weak from a viral infection. "Grateful for what?" I yelled. "How did she know where she was sending me? She gave me away to strangers!"

Emma cradled my head as I screamed and shook uncontrollably. My sister-in-law quietly left. My mother didn't say a word. She didn't even try to console me. Maybe she cried, I don't remember. I didn't even kiss her good-bye the next day.

I arrived in Miami with nothing but the clothes on my back. Seven days earlier, I'd left with more than $2,000 in cash and now, I didn't even have enough for a cab ride. Billy was waiting for me at the airport with a bouquet of flowers. He was older and grayer than the man I'd met on the Fifth Avenue bus years earlier, but his eyes were just as bright and blue as they were then. And he looked so happy to see me. I fell into his arms, sobbing.

I was finally home. And I knew right then and there that I would never go back to Cuba. Ever.

~

Lydia Martinez Brown's mother Consuelo Calves, passed away in April, 2003, in Cuba. She never saw her daughter again.

~

I wrote this poem after my husband Peter and I visited Cuba in 1998. Like Lydia, I was struck by the abject poverty but I managed to see the generous spirit of the Cuban people and the hopelessness of their situation, strangled by Castro's regime. We got to meet Peter's grandmother Consuelo, who was even older and more frail by this time. She hugged us fiercely and boldly told us that she wanted a great grandson. (Oddly enough, our son David was born 10 months after our visit.) For some reason, I wrote it in the third person, as though it happened to someone else, perhaps to create an protective layer.

Mi Cuba

by Catherine Gigante-Brown

For mi abuelita, Consuelo Calves, who died April, 2003, in Cuba

On the rooftop bar of the Hotel Inglaterra

Ricardo sings

in heavily-accented English,

not el sons, mambos,

or the bittersweet ballads

of his country,

but the longing for another.

Scattered about

are newfound friends:

a married couple from New York,

a man from Texas,

two more from Louisiana,

human contraband

defying the embargo.

One has una abuela vieja,

an old grandmother,

wasting away in Playa Marinaeo,

spine frail as a bird's,

yet an embrace of iron.

Another desires

the pepper of smoky-sweet

Monte Cristos on his tongue,

and the others,

the tang of jiniteras.

Sipping mojitos,

ron e coca

(con Tropicola, no Coca Cola, por favor )

and cervezas

as Ricardo cradles

his battle-scarred guitar

like a weapon,

the words of John Lennon

bring tears to their throats

which they choke back

with alcohol.

"Imagine there's no countries

It isn't hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for…"

My Cuba is beautiful.

My Cuba is kind.

My Cuba is hungry.

My Cuba is not.

Castro's failed Communism or clandestine Capitolism.

My Cuba is right here,

right now,

on the roof

of Havana's Hotel Inglaterra,

not a place of politics

but of people.

Un pais del gente.

A place of people and song.

And of hope.

My Cuba. Mi Cuba.