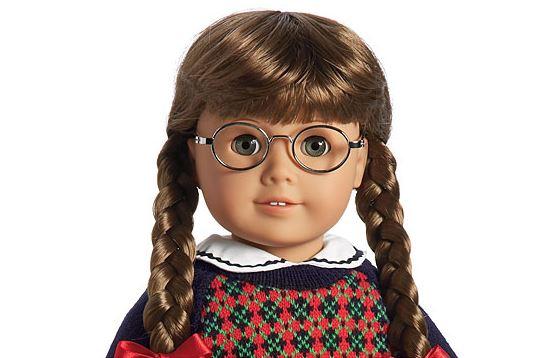

I don’t remember how I got into American Girl—I think likely through some data-sharing situation with other publications, the catalogs just started showing up at my house. I didn’t know what they were at first, these odd-looking, stocky dolls with boxy torsos and off-puttingly identical faces, dressed in period garb. All I'd really been exposed to up until then were Barbies and their beautiful ilk, and honestly, I kinda thought American Girl dolls were ugly at first (still do—their trademark sticky-outy teeth make them look like babies, which is just creepy). But the catalogs kept coming, and over the course of the next year or so, I would start begging my parents for a Molly doll for Christmas.

I thought I was the only one who was into these weird historical dolls for a while—since when has history been trendy among 9-year-olds?—but I soon found I most definitely was not. Hundreds, possibly thousands of girls my age were obsessing over American Girl dolls and products in the mid-‘90s.

Created in 1986 as both teaching tools and lifelong friends for young girls, American Girl dolls—and, by proxy, the accompanying books that told each doll’s story—achieved almost a cult following. Each doll in the collection was a girl from a moment in history: The canonical three were Kirsten from 1854, Samantha from 1904 and Molly from 1944. Other dolls, including the popular Felicity and the line's first dolls of color—African-American Addy, Latina Josefina and Native-American Kaya—would come later.

The dolls weren’t really anything special (though the price implied otherwise), but they employed some of the same enticing sales tactics as Barbies: You could buy outfits that matched the ones worn in the books. You could get exclusive additional books, like paper dolls and cookbooks with historical recipes. And the miniatures! Oh my god, the miniatures. Each doll came with a treasure trove of tiny accessories, and they were all just SO CUTE (overpriced, but cute). Molly’s kitchen set is the sole reason I want Fiesta Ware for my own house one day.

But that’s not the only reason Molly was important to me: She was, truly, the best American Girl. Because unlike so many other dolls, she was a spunky, adventurous, defiantly un-cool, not-conventionally-beautiful geek.

She was, in other words, a doll a girl like me could relate to.

In the books, Molly is a scrawny, goofy kid growing up in suburban Illinois while her father’s away at war—not fighting, of course; he’s safely tending to wounded soldiers in a hospital. Meanwhile, Molly makes do on the home front—she goes to summer camp, she spats with her older sister, she envies her rich neighbors. Everything about her resonated with my own life. She liked performing—I was getting into theater at the time. She wore glasses. I wore glasses. She wasn't cool, but didn't care. I had one good friend at the time, but spent most of my time at home with my parents, a lifestyle I was completely OK with.

She also defied every convention of beauty little girls are told to aspire to. She had brown hair. She had freckles. She wore her hair in braids. Molly was everything that often implies ugly in our culture. She was obviously, aggressively different.

Molly’s character was a little more complex than that of her peers; there’s a heavy dose of pathos in her story. The constant danger of her dad dying (Spoiler alert: He comes home on the last page of the last book and gives her a big hug, and reading it might have been the first time I ever cried happy tears) and the dark irony of her sunny home-front life while people are being bombed into submission overseas was always kind of hinted at: She names the capital of England in Geography class, then fesses up that she's familiar with it because her dad's away at war there. While waiting for Christmas gifts from her father to arrive, her brother cheerily suggests that the plane carrying them, uh, could have been shot down.

There’s also her friend, Emily Bennett, a refugee child sent across the Atlantic to escape the terror in her homeland. Though she’s played up for fish-out-of-water humor, it was a very real thing at the time (if you ever need a good, cathartic cry, there’s a devastating documentary out there about the evacuee program for German children). The weight of Molly’s story is eclipsed only by Addy’s, whose books gently eased girls into conversations about the grim realities of slave life—such as not knowing your own birthday because you’re someone else’s property.

By the time my parents actually saved up enough scratch for that stupid doll, I was 10—an age at which playing with dolls was becoming a social liability. After playing with her a few times, then stepping on her glasses (my mom, smartly, refused to buy me an exorbitantly-priced replacement pair and instead made it an impromptu lesson in taking better care of my things), Molly was relegated to a box under my bed.

I’m going to be selling off my Molly on eBay soon—she was retired last year, and even with a wonky pair of glasses, she can still fetch more than what my parents paid for her. But in this time of toy-giving, I'm reflecting on the impact she made on me and, I'm willing to bet, a small subset of other girls, too—probably ones whose eyesight also started failing them at an early age. The company has greatly expanded its offerings since those early years, and Molly's been left in the dust in favor of on-trend, of-the-now, “cool” girls.

Though they still strive to reach girls of all kinds with their current line of products, they really started reaching out to the rest of us with Molly, the scrappy, bespectacled underdog that gave hope to blossoming nerd girls everywhere.

Images: americangirl.wikia.com