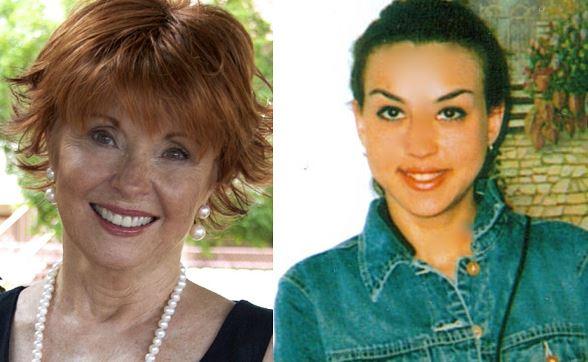

Sue Ellen Allen—a former prisoner, the author of Slumber Party from Hell, and founder of the non-profit GINA's Team—reached out to us after reading our Conversation series about women in prison. She also contributed a story about the experience of being prison strip-searched. Have a perspective or experience you'd like to add to the discussion? Email our editors at ravishly@ravishly.com.

I was supposed to die, not Gina. She was only 25. I was 57. She had her whole life in front of her; I thought mine was over. Why did she die? Why did I live to tell about it?

Jail is a hellish place for even the healthiest of people. The black and white stripes and living conditions breed anxiety and stress. There are lock-downs. There is pepper spray. There are brutal searches by the terrifying "men in black." For my part, I stayed on my bed with my nose in a book—at least my mind was able to escape. But the noise would continue all night, every night. Instead of silence, fellow inmates would yell at each other to be quiet.

“Shut up.” “No, you shut up.” “Shut the fuck up.” “No, you shut the fuck up, bitch.”

So it went, night after endless night. And here’s the irony: Every night at 10, as the lights went out, a prayer began. Lying on those hard, plastic mattresses, everyone said the Lord’s Prayer together. Then this followed:

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake, at least it will be on video tape.

Then the real noise starts and goes all night. Amen.

The incessant noise, violence, hostility and indifference of prison life overwhelmed me. I'd never seen people treated like this before. Many say prisoners deserve it. Maybe so, but here’s an analogy: If you take a dog, put it in a cage in the backyard, yell at it all the time and kick it a lot, then in a year or 10, let it into the house to socialize, you’re going to have a angry, confused, frightened, hostile dog. That’s what I saw all around me.

I struggled to keep my sanity and my health in this hostile environment. I had been diagnosed with stage 3B breast cancer on Valentine’s Day, six months prior to entering prison. I’d had a competent, compassionate oncologist. I’d had six sessions of chemo that were stressful but didn’t involve handcuffs or shackles. Now I was no longer a patient with cancer; I was an inmate with cancer—a distinction I learned very quickly. Those stories of great healthcare inside are just that: stories.

The mastectomy I’d imagined taking place in a comfortable hospital with my husband nearby was not to be. Instead I gained a new claim to fame: I’m the only woman to have had a mastectomy while a guest of the “toughest sheriff in the country.” And though it didn't take place in the prison—instead at the county hospital with real surgeons—it was still horrific. I’d never imagined facing my mastectomy in handcuffs and shackles.

Right after my mastectomy, I made a trip to court for sentencing. I hated those trips. They were a marathon ordeal without sleep or food. At the time, I’d lost 28 lymph nodes and was at high risk of lymphedema. I had an official note from the nurse in the medical department to security not to cuff my right arm. I showed it to the guard who shoved it back in my face and continued to cuff me.

“But, but, I’ve just lost my breast. I could get lymphedema,” I stammered. He refused to listen. “You could at least be gentle,” I said, tears welling in my eyes.

“I am being gentle,” he snarled. “You aren’t lying on the ground bleeding.”

Why was there a need for such cruelty? It crushed me. But later that day when I got back to the dorm, my old spirit kicked in and I did the unthinkable; I filed a grievance against the officer. I had a proper permit. He was wrong.

The next day, I was surrounded by the terrifying men in black. “Move,” they shouted as they searched my bunk. They flipped the mattress and shook out my few books and letters. I learned they were looking for a red pen to prove that I was the one who wrote the medical note and forged the nurse’s signature. A red pen! We’re only allowed a two inch golf pencil. Nonetheless, they came back twice more, yelling and screaming to intimidate me. And it worked. I was scared to death—but not scared enough to confess to a lie.

Later, I saw the nurse in the hall. She told me they questioned her several times, wanting her to admit I forged the note and she was trying to protect me.

You begin guilty—and then never proven innocent.

Finally, after six months in that hellhole of a jail, I was sentenced and the judge expedited my move to Perryville Prison, as I still had not received the chemo that was long overdue. The doctor told me surreptitiously that the jail delayed my treatment—hoping to get rid of me and save the money.

At Perryville, I told the apathetic check-in nurse about my medical situation. “Well,” she frowned, “the judge can expedite all he wants, but you’re in prison now and you can get in line.”

It was in this line that I met Gina, a beautiful young woman who surprised me by sitting with me for meals and wanting to be friends. With a 32-year age difference, I had no idea why, but I was delighted. I grew to understand our deep conversations nourished us, both of us starved for meaningful contact.

When, at last, my chemo started, I became very nauseated. Unlike my previous chemo treatments on the outside, this time I was incredibly ill and Gina begged to move in with me to act as my caregiver—care I desperately needed.

The normal diet in prison made me horribly sick, so one particularly miserable day, I struggled to walk the two blocks to the kitchen to beg for just broth or plain potatoes. Nope, I was told. There was nothing they could do. On my way back to my cell after this failed endeavor, I collapsed, vomiting.

An officer came and asked, “Can you walk the three blocks to medical. There are no wheelchairs.”

“I’ll try,” I murmured.

Partly across the soccer field, I collapsed to vomit some more. As I lay there, a sergeant came toward me, inconvenienced: “What’s the issue, Allen?”

How does one possibly answer that?

Cancer. Chemo. I’m sick.

I vomited some more. The sergeant’s shoes were eye level. Shiny. Not dusty boots like everyone else. I noted that he kept them well away from me. Weakly, I managed to pull myself up and continued across the field. No one helped me. By now, there were several more officers and a nurse. They walked behind me in a weird parade. I made it to the picnic tables in visitation where I stopped to vomit some more.

“Get somebody to clean this up,” the sergeant barked. No vomiting on the rocks.

When I finally made it to Medical, the visibly annoyed nurse put me in a room on a hard, cold table. She handed me a wastebasket as I continued to vomit. How could I vomit so much? The doctor was too busy to administer the anti-nausea shot. But there was no emergency; he was just doing paperwork. I vomited until there was nothing left and then I dry heaved until I couldn’t lift my head. An hour later, the doctor came in, obviously irritated. He acted like I was faking and reluctantly gave me the shot. I was dismissed back to my cell alone—where Gina was waiting with her compassionate heart.

Three more treatments of chemo followed. Despite the rigid schedule, the medication was never ready on time, nor was the newly discovered chemo diet available. I had to spend my sickest days walking the long distance across the field to Medical, begging for what was prescribed. Instead of healing, I was worn out battling for proper treatment. I couldn't understand the indifference. These were supposed to be health care professionals—and I was so sick.

As the property of the state, my life was in their hands—and they didn’t give a damn.

Chemotherapy ultimately ended and radiation began. Burning replaced the nausea. Meanwhile, one day in April, my cellmate, darling Gina, collapsed. Over a two-month period Medical treated her with the same hostile indifference that I was experiencing.

Naturally, I was worried sick about Gina. I cared for her for weeks and then suddenly I was not allowed to know anything. “Confidentiality,” they told me. B.S. That was just a convenient smoke screen. The silence was deafening. I got discrete dispatches from staff that Gina had leukemia. It was serious—but I knew leukemia is very treatable. I didn’t understand what was happening or why she wasn't receiving treatment.

Gina spent what would be the last week of her life in horrific pain—crying, terrified, ignored. Medical was hostile. No one listened. Because she couldn’t climb up to her upper bunk, she lay on mine, literally beating her head against the concrete wall, wailing from the pain. By the end, she couldn’t even walk. Our helplessness was enormous. On June 16, they finally took her to the hospital while I was getting my radiation treatment. The doctors told her parents her white blood count was 300,000 and her red blood count was ZERO. She had myeloid leukemia and hadn't even received a blood test. Her body had been shutting down, thus the excruciating pain.

Two days after they took her to the hospital—on June 19, 2002—Gina died. She died isolated and afraid, unable to say goodbye to her children.

When I returned from getting my radiation treatment, the cell was painfully empty and silent.

Still, my battle against cancer—and the unjust system that was denying me treatment—raged on. My chest was a mass of blisters. It felt like a tiny fairy was dancing on it with razor blades on her shoes. The nurse said they didn’t have my meds. Why couldn’t I get them? Why was everything such a battle?

Finally, my treatment ended. The radiologist said he or the oncologist would see me every three months for two years, then every six months for two years and then annually. But no one saw me.

Eighteen months after I last saw the radiologist, I was allowed a teleconference with an oncologist who was completely unfamiliar with my case. He answered my questions, but he’d never seen my file and there was no way to examine me. He recommended a tumor marker test. Six months later, no test.

The oncologist said I might live five years if I was lucky.

Gina and other friends were dead. We, the living, felt completely alone and terrified for our own welfare. In a hopeful moment of seeming insanity, I asked to start a Cancer Support Group. It took me a year of begging, but finally, success! Permission was granted. We had fifteen members, all of us with terrifying stories of neglect.

Cancer is a condition to fear, but you can face it. The justice system and prison, however, are another story. Facing prison with cancer takes fear to a new level. Even with a positive attitude, I couldn’t change the horrible conditions, apathetic nurses, indifferent doctors and mean-spirited officers. When they made decisions that literally affected my ability to live, I was helpless.

That’s what fueled my fear. No amount of platitudes or positive imagery could change the situation. This wasn't irrational fear about some hostile guard or stupid rule—that I could have dealt with. This was about the state, an enormous multi-tentacled octopus that formed an impenetrable wall of incompetence. How does one deal with that?

How does one find the light in the darkness?

In every circumstance there are choices. No matter how dark, we can choose to stay in that darkness or look for the light. I chose the light. Somehow I decided to take my pain and fear, to use it to become stronger and more positive. I wanted to make a difference . . . and you know what? I have, thanks to Gina’s Team and all the volunteers who share my vision in Gina’s memory. Miraculously, I now go back into the same prison where I lived for seven years. We collaborate with ATHENA International to teach the ATHENA Leadership Model. We have a 5% recidivism rate compared to the national and state average of 60%.

So what did I learn in prison? We always have two choices: never give up or never give up. No matter how dark, I believe you can find the light, the power and the purpose to make a difference in this precious world.

That’s why I lived—to tell about it.