Photo Courtesy of Georgia Ponirakou

Minnie first notices the rip when tilting her face toward the bathroom mirror. She leans in over the pedestal sink, turns the cold water spigot off, and peers at the half of her face that remains. Her face has been torn in two.

Change has always been difficult for her. Her colonial sold right out from under her after the divorce. Her twin daughters waking up one morning with breasts poking through their pink undershirts. Three brown age spots appearing one evening under her left eye. She should know to expect these things, to prepare a face.

She examines what remains. Richard had looked at her the same way when he stumbled into the master bath and saw Minnie with her makeup half applied. If only he could see this half face staring back in the mirror now. Minnie allows herself a moment of levity, a vision of Richard tumbling backward into the tub behind her. The bumping of his elbows, knees, and skull on the porcelain.

A trick? The twins’ idea of a practical joke? Should she look behind the curtain? She pauses with her toothbrush clenched in one hand and touches the mirror with the other, feeling for the texture of paper and edges of tape to peel away. But there is no paper, only the smooth, cold mirror. She shuffles forward on the bath mat and leans closer to the mirror, slowly waving one hand back and forth through the space where the right side of her face should be. Yes, her face is torn vertically from the top of her scalp, where she parts her hair, to her chin.

The curtain is still. This is no trick.

The toothbrush clatters into the sink. With both hands, she feels the ragged edge of the right side of her face, which is attached to her neck. Rather, tucked, like a Kodak in those little black corners people would lick and press onto the pages of a photo album. Two-dimensional, at least extremely thin, no space for a brain, bone, nerve, persistence of memory. Torn apart, like a photo of an ex.

Though Minnie is a bit pixelated, she notes that her coloring is correct. One ocean-green eye, pinkish half lips, a pale morning cheek, half a furrowed brow. Unfortunately, the side with the three brown age spots is the one she has left. But where the rest of her face should be is the reflection in the mirror of black and white tiles and blue shower curtain. She feels collaged. Cubist.

There is nothing humorous about this. Detached retina, cataract, some sort of strabismus? She wonders if tunnel vision is necessarily round.

Minnie raises and lowers both arms and pinches herself. No numbness. She says to the mirror, Testing, one, two, three, and the words come out as she intended, not gibberish. But muffled. Which is understandable enough, considering that half the air passing through her vocal chords has nowhere to go.

This is not a stroke.

The photo lips move, in a stuttery, home-movie sort of way, but they move. Testing, one, two, three.

She can see out of her paper eye. There is a torn edge, deckled like good stationery, in her field of vision, but otherwise no distortion. The rectangles of towels hang as they should. The lettering on the Colgate and Listerine bottles is sharp and reassuring. Every few seconds, the one eye blinks as any eye should blink.

She is not in pain. There is this sense of, if she has to name it, placement. Installation. An assemblage of straight edges.

Shivering, her robe hanging on a hook, she thinks of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. All those fleshless rectangles in counterclockwise downward motion. Bending her half face to look at what doesn’t appear in the mirror, she sees a house of cards. Could they descend the stairs to the kitchen neatly as the artist’s nude, her geometry intact? Or would she collapse, her hearts, clubs, spades, and diamonds scattered down to the landing. Splayed at the front door with boots and backpacks.

She considers calling out to the twins, who are already downstairs in the kitchen laughing and bickering. She could say, girls, could you come here for a minute? Do you notice anything different? As if she had a new mole, not a face, with uneven edges.

But their worlds are complicated enough. Their house has already split. The last thing either of the girls needs right now is a mother with half a face and a house of cards for legs.

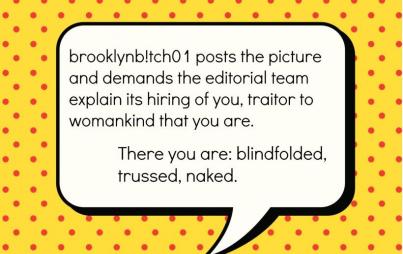

Where is her other half? She spends so much time in the kitchen, making a home movie life of what they have left. She imagines one of the girls finding Minnie’s other half draped over the toaster oven like Dali’s melting pocket watch, pinching it by the hair, and lifting it up for her sister to see. She would say, “It wasn’t there before I put my bagel in.” One eye would blink at her and the half mouth would try to say something other than “testing one, two, three.” Her twin, who would always have a rational explanation, would say, “Oh, cool. It’s digital,” and she would lift the edges up carefully, so that it wouldn’t rip, and lay it over her own face, where it would seal itself onto the features so like her own. She would think that she could take it off later, with Mom’s Ponds, because Ponds takes everything off.

No, not everything. So Minnie stays put, teetering but still. Balanced on a half deck of diamonds and hearts.