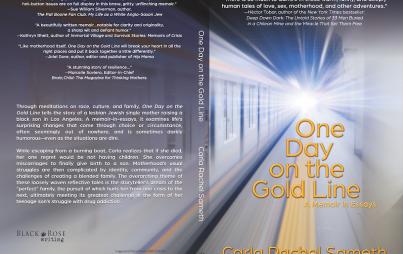

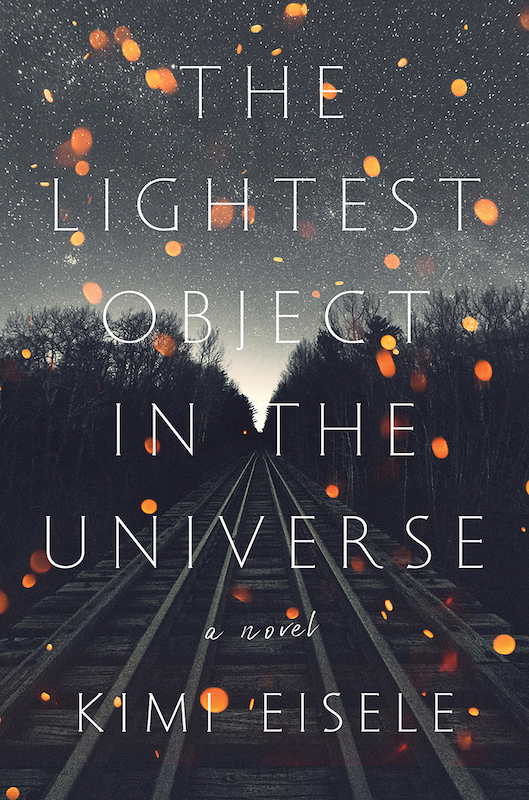

The Lightest Object in the Universe by Kimi Eisele

What if the end times allowed people to see and build the world anew? In Kimi Eisele’s debut novel, The Lightest Object in the Universe, Carson, on the East Coast, is desperate to find Beatrix, a woman on the West Coast who holds his heart. Working his way along a cross-country railroad line, he encounters lost souls, clever opportunists, and those who believe they’ll be saved by an evangelical preacher in the middle of the country. While Carson travels west, Beatrix and her neighbors begin to construct the kind of cooperative community that suggests the end could be, in fact, a bright beginning.

1. How much did the state of the world influence the narrative of The Lightest Object in the Universe?

Very much so. I started writing the book over a decade ago. The US was at war with Iraq, and, in some circles, the conversations about peak oil were getting louder and more insistent. I started wondering what would happen if the country was stripped of its Superpower status—both its global political power and its electrical power.

I was struggling to write about American exceptionalism in nonfiction essays, so I decided to craft a fictional world in which the plug really did get pulled.

I think I just wanted to level it all and see what might happen. Over the years I wrote, I felt like current events were always alongside me, mirroring the novel. There was the 2008 financial crisis, the 2016 election, and of course, the ongoing climate crisis. The real apocalypse seemed to keep inching closer and closer. It still feels that way! But what I came to discover through my characters is that we might be more resilient than we think, especially if we foreground kindness and practice generosity.

2. Which character in your book do you most identify with?

More than one! The story follows two characters on either side of the country who are cut off from one another in the collapse. On the east coast is Carson Waller, a high school principal trained as a historian. Part of me is like him—observant, chronicling, trusting. He’s also got stamina, as he travels on foot across the abandoned railways in hopes of finding Beatrix, a fair trade activist on the other side of the country.

Beatrix is like a verb. She’s a doer and quite convinced of her ideas, sometimes to her detriment. She reminds me of a younger version of myself.

Then there is Rosie, a 15-year-old girl who makes a journey with her grandmother to a place called The Center, where an evangelical cult leader is luring the masses with promises of material comfort and redemption. Rosie witnesses a harrowing event and must find her voice in order to find safety and community. I think all three of these characters taught me a lot about myself and about the process of writing a novel. Stay with it; just do it, and trust your voice.

You Might Also Like: Music, God, Love, Desire: In Conversation With Cameron Dezen Hammon

3. As a multidisciplinary artist, in what ways do your different practices influence each other?

I think working in different forms (literary, dance/theater, visual) allows certain parts of my creative brain to rest while other parts take over. In performance work, I often get a very visual image in my head, some sort of flash scene, like people dancing in formal wear with saguaro cacti in the desert. Then I build a project from that vision. The end result may not match that initial vision, but it’s the flash image that gets me started.

I practice a form of dance/movement called, Compositional Improvisation, which has roots in jazz and some of the avant-garde dance and performance work from New York’s Judson Dance Theater in the early 1960s. It’s a form in which you work in ensemble, with other dancers, musicians, and sometimes poets to create ephemeral, improvised compositions. Sometimes we just do it in a studio for ourselves, sometimes we perform.

This work has really shown me the power of the “laboratory,” just letting the process of making be an experiment.

Dance is easy this way, because it’s here one second and gone the next, so you can’t be too precious about it. I find when I write, I can get precious. Words on a page can feel so serious, so permanent. But it’s all an experiment and remembering that can keep it a little more playful, less serious.

4. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received?

Many years ago, I took a fiction writing class in college with the late Paul West. On the first day, he had us write down on a little note card how other people had described our writing. I had nothing to write. Later, once we started writing stories for him, he would type up short comments on little slips of paper and staple them to our stories. Once, he typed the word “trenchant” to describe one of my stories. It was such a great word! I promised myself I’d never forget it.

All this to say, he pushed us to think hard about the words we used to describe things. He made us reach for words that were interesting and underused. He was a poet in this way. I remember him praising at length a classmate’s use of the word “celery.” I remember a few of us laughing about it at the time, but West’s emphasis on word choice stuck with me. It was good advice, and the fact that I remember it in tandem with the words “trenchant” and “celery” has kept it vivid.

5. What are you reading now?

I just finished Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments and loved it. Right now, I’m reading Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, which is indeed gorgeous. I’m also listening to Robert Macfarlane’s Underland: A Deep Time Journey, which is a poetic and fascinating book about the worlds beneath our feet. Up next are Richard Powers’s The Overstory and Erika Swyler’s The Light from Other Stars—I’m excited for both.

Kimi Eisele is a writer and multidisciplinary artist. Her writing has appeared in Guernica, Longreads, Orion Magazine, High Country News, and elsewhere. She holds a master’s degree in geography from the University of Arizona, where, in 1998, she founded You Are Here: The Journal of Creative Geography. She has received grants from the Arts Foundation of Southern Arizona, the Arizona Commission on the Arts, the Kresge Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. She lives in Tucson and works for the Southwest Folklife Alliance. The Lightest Object in the Universe is her first novel.