If you were to ask me what the single most important and influential factor of my life was growing up, I would tell you religion without even the slightest of pauses. More than school, friends, and even sometimes the lessons I learned at home — my faith was in many ways my most consistent and authoritative instructor. Though I've since left the faith I was raised in, I'll always consider Mormonism as my homeland, my culture, my hearthstone. I would not be who I am without it, and for that, I am forever grateful.

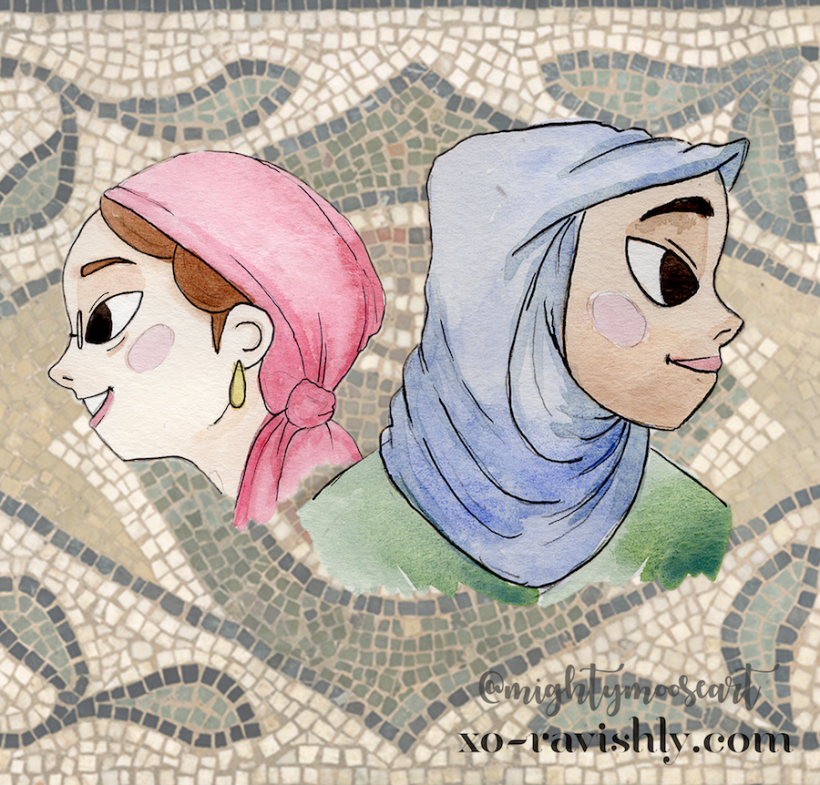

As a result, I have a deep fascination with religion and a passion for protecting the freedom to express it. I feel a magnetic pull to religious narratives, which is part of why I created the "Religion & Feminism" series for Ravishly's Conversation. It was through that series that I became aquainted with Shoshana and later Saadia, two women who run an incredible website that serves as a platform for parents from every faith background imaginable, including themselves. Shoshana is an Orthodox Jewish woman living in Israel and Saadia is a Pakistani Muslim woman living in Texas.

Have Faith, Will Parent positions religion as a common experience we can start from rather than a junction for division and discord, and Shoshana and Saadia's very partnership stems from this belief. The same can be said for parenting styles and methods, especially in the age of the internet. Combining the two makes for a dynamic exchange of ideas and cultures, and I was happy to talk with both Saadia and Shoshana about their writing and work as religious mothers from vastly different backgrounds.

What challenges have you faced in discussing two topics — religion and parenting, respectively — steeped in disagreement?

Saadia: I honestly haven’t found it too difficult. I think the internet has really opened up these discussions in a way that wasn’t possible a couple of decades ago. There are so many blogs and articles that offer advice I need, and groups I can join to share my experiences. Probably my biggest challenge has been moving away from more traditional parenting ways that are the legacy of my Pakistani parents and grandparents. South Asians have a particular way of parenting that involves more culture than religion, and my aim has been to reject that in favor of religion. What does my faith teach about raising kids? Who are my role models in terms of being a good mother? How do I manage the struggle of being a parent with the struggle of being a Muslim in America? It’s been an interesting journey.

Shoshana: We tend to live in silos, or bubbles, or whatever metaphor you choose that indicates a kind of communal isolation – we’re in isolation with other folks like us. And I’m not excluding myself here; I very much live in a bubble. Almost everyone I know is Jewish. That’s where Have Faith, Will Parent comes in, especially the Facebook group component: We’re trying to use the powers of the internet for good, by breaking down these artificial barriers rather than reinforcing them, and by giving people a way to connect with those they might never have encountered otherwise. As for talking about parenting, I guess it’s just the stage we’re at in life. I’m in the midst of this parenting adventure – my youngest just turned 4 in April and my oldest is turning 10 in the fall – and so is Saadia (whom I’ve never met in real life, by the way), so it seemed natural to focus on challenges and insights and questions related to parenting.

I grew up in a fairly traditional Mormon family, and I remember Sabbath as the day I dreaded above all others because it was SO BORING and sometimes we even HAD TO FAST #ugh. Looking back, I miss having a whole day dedicated to rest and ritual, so the idea of Sabbath has become something that I think about a lot as a secular adult. How does having holy days and/or times of day change the way you live the rest of your life? How can people bring these principles into their own lives, even if they aren’t religious?

Saadia: Muslims don’t really have a day of rest, something Shoshana and I write about in one of our articles for Catapult. But actually I prefer that concept of taking time out when everybody around you isn’t slowing down. It’s like one of those camera tricks we see in movies when the main character is still and everything around it is spinning fast. Friday is still a school day for my kids, and a work day for us, yet we take time to pray at the mosque and meet with friends and family. It makes the day even more special than it would normally be. I think this is something people who are not religious can easily do: choose a day or even a few hours of every day to do something with your family. It could be meditation or going on a hike in the woods, or just reading. The point is to choose to slow down, even stop the daily grind of life that leaves you so exhausted and stressed out.

Shoshana: As a working parent, my week is a constant logistical minefield, and I think that’s true for a lot of people trying to meet deadlines and arrange playdates and go to the dentist, and the list goes on (and on and on and on). But all of that gets suspended on Shabbat. It’s not that there’s no squabbling or no conflicts of interest between my needs and those of my children on Shabbat; there often are. But the religious constraints on doing work and using digital or electronic devices means that I don’t feel any guilt about not sending out that one last email or crossing one more thing off that never-ending list, because that burden has been lifted for 25 hours. The juggling might not fully cease, but the number of balls in the air dwindles.

I think people can do this in their own lives as well – go on a digital diet once a week. I would recommend finding a group of people to do it with you, though, because I think it would be harder and require a lot more willpower to do it without a community of some sort for support.

Let’s talk clothes — you’ve both written about modest and religious dress as mothers. There’s a lot of pressure on religious parents — women especially — from the outside world to let their kids wear “normal” clothes, but for a lot of people, religious clothing is the norm. What do you wish more people understood about religious dress and modesty, and what do you wish you had been told about it as a child?

Saadia: I think modest clothing is a pretty big deal, especially in a culture that promotes a certain body image that’s not always reflective of a real person. My kids dress pretty normally, except for very revealing clothes such as a bikini. But the great thing is that this concept isn’t limited to religious people. For a number of reasons, more and more parents are questioning the styles our youth are being bombarded with in media. For me at least, the only real distinction is in the hijab, the headscarf and related clothing like a coat or a face veil that many Muslim women wear. I write about hijab frequently, because it’s such a misunderstood piece of clothing, especially since growing up I didn’t really understand it myself too well. These days it’s a very politicized topic, and so more and more Muslims are writing about it, such as this recently published anthology Mirror on the Veil, to which I’ve contributed an essay.

Shoshana: I think the need for understanding cuts both ways. There’s a tendency among some Orthodox Jewish communities to place an outsize emphasis on what girls and women wear. One problem with this is that focusing on women’s bodies and how they’re clothed takes away from a focus on the many other ways women can participate in Jewish life. It also effectively exempts men from their responsibility to keep their eyes and hands to themselves.

Outside religious circles, there’s this prevalent concept that covering up too much is inherently oppressive. But this comes with its own set of problems, primarily that it presumes women can’t think for themselves or make their own decisions about how they dress.

Religion has such a huge influence on how people parent, even in houses that aren’t particularly religious! And yet, we shy away from it so often and miss out on a lot of amazing conversations and stories worth sharing. What can we do to make these conversations more accessible to mainstream audiences?

Saadia: I see more and more faith-based writers sharing their stories about parenting on the internet. Books about families in other cultures are an important resource if someone wants to learn some different parenting styles. I would suggest non-religious parents meet people of other religions, join interfaith groups or book clubs that encourage those discussions. The most important thing to remember is that instead of being judgmental we should try to find commonality. For instance, you may think that expecting your daughter to wear a hijab is unfair, but when I tell you that research shows youth wearing hijab have more positive body image, you may reconsider. Or as another example, if you want your children to teach responsibility and dedication, you may be surprised to learn that stories of men and women from the Bible and the Quran (and other scriptures) address these exact issues in bedtime stories.

Shoshana: I agree that there are a lot of conversations and stories worth sharing. My prayers may look and sound different from Saadia’s, but it’s the same act at heart. And that’s true of so many issues. People get distracted by the differences, when really what’s most striking is the commonalities.

What’s also interesting is that not only can people use their personal experiences with religion to help them relate to people from a different religious background, but sometimes hearing a different perspective can give people insight about their own religion. For instance, a Jewish friend who’s in our Facebook group told me she couldn’t understand why her fellow married Jewish women would cover their hair (as I do). But she said reading an essay Saadia wrote on talking to her daughter about wearing the hijab made it easier for her to see the positive side. As for what we can do to make these conversations more accessible, I think it’s important to acknowledge if you live in a bubble, just as it’s important to try to poke a hole in that bubble – even if it’s only a small hole.

What is a part of your respective religions that you feel is especially helpful or meaningful to you as a parent?

Saadia: Personally, the example of the Prophet Muhammad as a parent and then a grandparent has been especially enlightening. I find myself reading those accounts over and over, thinking about them, figuring out how similar the life of a parent is no matter what the century. There are beautiful stories of him kissing his children, his grandchildren, showing kindness and affection. Sometimes as parents we forget how important this is. Especially in the South Asian community it’s seen as a weakness, as something negative, if you’re hugging or kissing your children. I really think this sort of example – when a religious leader can show you how to be a good mother or father – highlights how relevant religion can be to people’s lives.

Shoshana: I’ve always connected most to the intellectual aspect of Judaism, and I love the concept that there’s always more to learn, even if you’ve spent your whole life studying Torah. You see this in the holiday of Simchat Torah (which means “Rejoicing of the Torah”), where you finish the annual cycle of reading the entire Torah, and then you immediately begin again. I think this is an important lesson for parents as well as children. I’m not done learning how to parent just because my kids can all dress themselves now. Parenting requirements change in accordance with each child’s needs at each stage of development. And my daughter isn’t done learning math just because she passed a test on the times table. Learning is a lifelong endeavor.