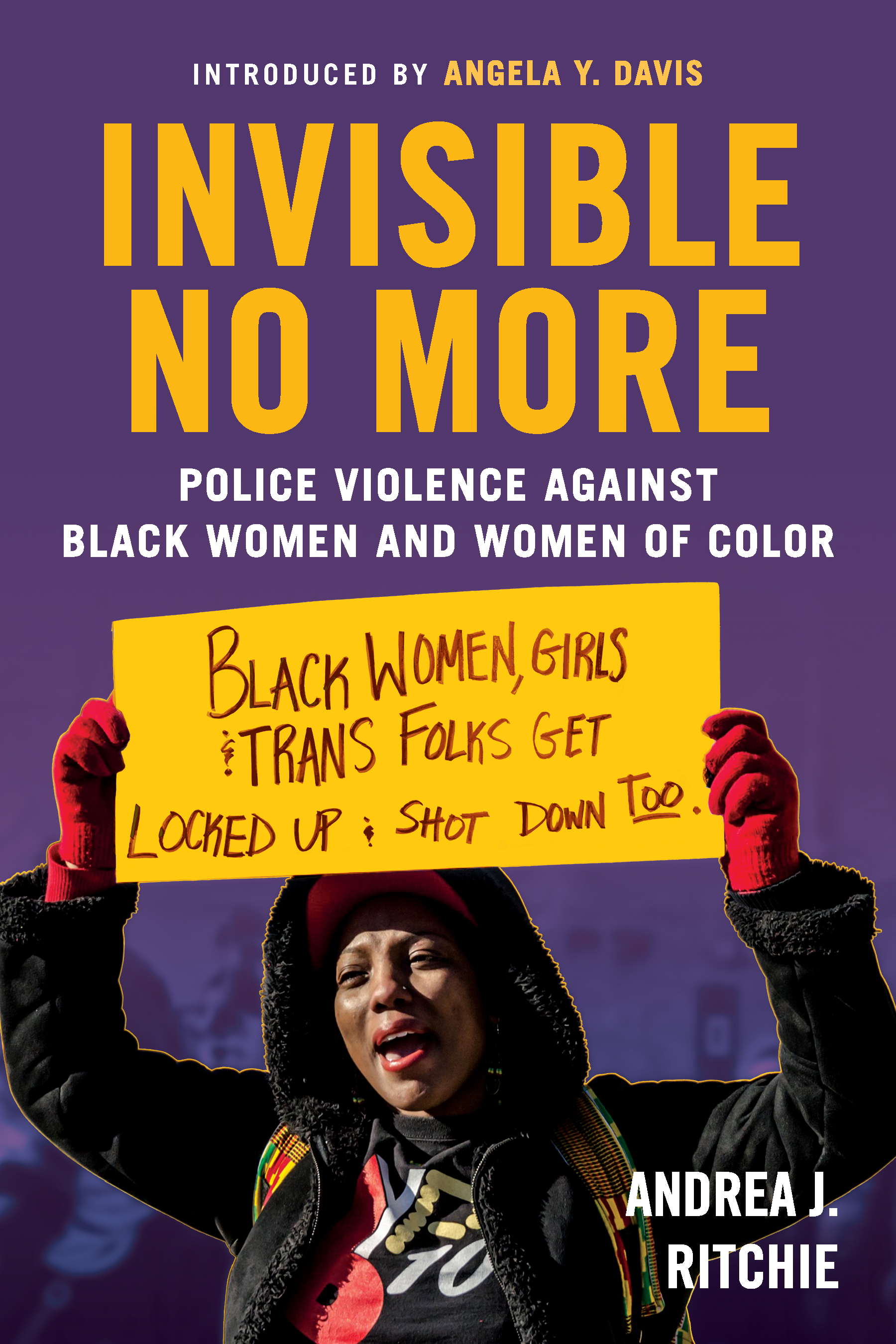

There are some books we read because they are good, and some that we read because they are important. Invisible No More is one of those books that is both good and important. It's a book that everyone should read because we don't give nearly enough attention to the issue of police violence against women and girls of color. Michelle Alexander calls it "a passionate, incisive critique of the many ways in which women and girls of color are systematically erased or marginalized in discussions of police violence." She also thinks it should get a standing ovation, and I'd have to agree with her. The body of work Andrea Ritchie has collected and presented will serve as an invaluable resource for feminists of the future, and will help to ensure that that future is one where women of color are safe from state-sanctioned violence by police officers.

The past few years have been punctuated with an urgent refrain, a reminder that #BlackLivesMatter in the face of police violence and mass incarceration. While it's an absolutely necessary conversation to be having, it can be rather limited; most mainstream discussions of police violence center cases involving young, cisgender black men. Most people easily recognize the names Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner, while Charleena Lyle's death is quietly put aside after a brief burst of press. Searching "Eric Garner" in Google yields news stories up to just two days ago detailing the family's wrongful death settlement. A Google search of Charleena, who died just this summer, yields only initial reports of her death. She was shot in front of her children by the police responding to her 911 call reporting a possible burglary. She was pregnant.

Invisible No More asks for a world where both stories are told.

It endeavors to create a world in which those stories no longer happen — one where both Eric and Charleena would still be alive and well today. Andrea Ritchie has dedicated her life to helping make such a world, Invisible No More being the latest of her research and writing. I called her to talk more about the book and the revolutionary magic of endeavoring to make even our most radical politics more intersectional. What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation together.

The thing I keep thinking about with Invisible No More is what it says about the conversations we have that we consider "woke" — that even in activist communities, this issue is so underrepresented and so overlooked.

That's why I ended up feeling like I had to write a book. To just kind of pull together what there is out there, because I feel like there are people who have been raising awareness of their own cases or those of their family members who they've lost to police violence, who have been raising issues that are particular to how women experience policing and police violence, and just consistently not being seen or heard or integrated into that larger conversation about racial profiling or police brutality or mass incarceration. It just felt like there was a lot out there, and that if you could put it all together in one place and put it out there, that hopefully that would shift things. And I do feel like in the last two years particularly... You know, Sandra Bland is very much on my mind today, because today is the second anniversary of when she was arrested.

[She was arrested] for not using a turn signal when she was trying to get out of the way of the police officers that were rolling up behind her with their lights on. And then I mean, I'm driving right now as I'm talking to you. Because I'm talking about it, I'm using my turn signal, but that's not always the case.

Yeah, of course. Like forgetting to use your turn signal is sometimes just the human thing to do.

Yeah. I mean, millions of people every single day fail to use a turn signal, and a much, much smaller fraction are ever arrested for it. And for many folks that's not a deadly decision. I think it just felt to me like the tide just changed around 2015. Young black women in Ferguson and other places around the country were demanding and insisting that black women's stories be told and heard and be part of a larger national conversation when Black Lives Matter was happening, including the leaders who were making that clear as well. The tide turned in terms of people starting to talk about it more.

But the thing is, you're talking about it to make it stick and also to make it actually part of how we think about the issues, so that we're not just thinking about Sandra Bland on one day, remembering her case on one day — but to have us think about Sandra Bland's case differently or more expansively. To think about driving while black, about what police brutality in the context of traffic stops looks like, and what kinds of policing of black women's presentations occur — wondering why they can't smoke a cigarette in their own car, how that's interpreted by police officers.

But then also thinking about other questions that it brings up, like the questions on bail. Why did Sandra Bland have to sit in jail of three days for failing to use a turn signal? Because someone said that it should cost her $500 to get out. [We need to be] thinking about the role that plays.

I'm hoping that it goes beyond saying a new set of names and actually really changing how we think about everything in this conversation, both in the conversations around policing and racial profiling and the silent mass incarceration, but also in the conversations we have about violence against women.

What would you say to someone who is in these activist efforts and is in what you called the Netherworld? Where they're feeling underrepresented or misrepresented, and they're not seeing themselves in the things that they're fighting for.

Find like minded people and start asking questions of each other. One of the things I talk about in the book is just having conversations with other black women in workshops and in other places and just naming, for instance, police violence against women, and having people be like, "Oh," and then they start talking about their own experiences in ways that they've never felt empowered to before.

One of the things that I've been trying to document in the book is that this has been happening for a very long time, since Angela Davis was talking about her own experience with police violence and then those of other women in civil rights and black liberation struggles. It's a conversation that's been going on for a while, but there hasn't been a true line linking that with broader movements around police violence, state violence, and violence against women and gender-based violence.

Yeah, we've just never thought to synthesize all of it.

I think it really is about just talking about it, because I think the more we keep talking about it, and the more we make space for those conversations to happen, then more people can come out of the Netherworld between police accountability movements that are focused on the experiences of cisgender men of color, and anti-violence movements that are focused on non state forms of violence [against women] and how can we bring those conversations into the center of both. I talk about it in the book — about how it's just a question of saying it in a workshop and then suddenly experience after experience comes forward, and that's not unique to this moment.

There's one meeting I described in the book that's also described in Diana McGuire's book, At the Dark End of the Street, where during the civil rights movement, some leaders of women of color clubs that were fighting for justice held a meeting and started just talking about their own experiences with police violence, and by the end of the meeting everyone had shared an experience of police violence. But that's not the dominant narrative of the civil rights movement so how can we file it as manifesto, right?

I feel like it's just about making space to talk to each other about our stories, but also to link those together into a broader story.

Yeah, and I think that really calls back to what you were talking about earlier, about how this needs to be something that changes the way we look at this issue as a whole. It's not just that women and non binary people of color who experience police violence need to have a moment, it's that they need to be part of how we talk about it, period. And calling on all of the past conversations that have already been happening, it just feels like a further testament to that, you know? it's not just right now, it's a past and future thing.

Absolutely. One way in which that would play out, for instance, is the current federal administration is signaling very clearly their intention to ramp up the war on drugs and return to very aggressive, harsh drug enforcement policies and practices of the 80s and 90s, which we know from experience not only drove an 800% increase in black and brown women's imprisonment, but also drove tremendous police violence against black and brown women and immigrant women and LGBTQ folks during that time.

Because we don't just wind up in prison one day — someone puts you there. And usually it starts with a police encounter where an officer decided that you looked like someone who might be carrying or selling drugs or that they needed to target for carrying and selling drugs.

It's about looking to everything this administration is proposing and saying and asking, well how is this going to affect black women and women of color?

We talk about intersectionality like it's this radical thing, and it is, but there's also this part of it that's such a bridge-builder. Intersectionality is about considering everyone, all the different aspects of humanity and ways of existing that there are. It's a way to connect with this broader group of people in the resistance.

Absolutely. I think that in Angela Davis' book, Freedom Is A Constant Struggle, she talks about intersectionality of movements as well as intersectionality of identities and how intersectionality of identities can build intersectionality of movements. That it's important to keep both in the frame and have them articulating with each other as they move forward, and also talking about how intersectionality really comes out of people's lived experiences.

There are places in the book where I talk about how focusing on police violence was a way to bring together queer and black communities through the experience of police violence against black and brown lesbians, for instance. And that often it's difficult to build across difference if we're not talking about shared experiences — and obviously the experiences aren't identical, but they're still ones that we can build solid ground on together.

Yeah. It's an idea that is so often characterized as divisive, as the opposite of what it really is, and I think that's one of the most amazing parts of the book. You can feel the issue opening up, and feel that that is actually what it is like when we consider marginalized experiences. It's not myopic to do that.

That was definitely the goal, so I'm glad that that was successful. It was about expanding the lens, and seeing how things play out in a kaleidoscopic way. Just looking at similar things from a different perspective or in different places can really broaden our understanding of the issue across the board in ways that ultimately make all of us better equipped to resist multiple kinds of oppression.

And I think that using a personal inflection in it is also a really awesome way to drive the point home. I kept thinking about how much the way that you insert yourself in your work reminds me a lot of Audre Lorde's work, especially Zami, and how the tradition of telling an emotional and personal experience is discounted so often. In this case and in so many cases, it's absolutely what we need to be hearing.

I'm so moved that you would say that. Obviously, Audre Lorde is a huge inspiration to me and I really love that one of the forwards to the book quotes one of her poems about Eleanor Bumpurs, who also was very instrumental to my growing awareness around these issues. Yeah, I mean this is a story that's sort of become my life's work, and obviously not only mine. Many, many people have spent their life's work, whether it's for an individual family member or for their community, or on this particular issue, but it felt important to share a journey to awareness and to the current moment as someone who's lived through 20 years of struggling on this front.

It's usually difficult for me to speak from personal experience in that way, but it felt like the most authentic way to share the information that I had the privilege of gathering through struggles alongside many visionary activists over the years. I think that it also felt torn, because I was constantly saying why, as women on the front lines of struggles for police accountability, are we not telling our own stories? I felt like I kind of had to turn that question on myself.

Well, before we wrap up, was there anything else that you wanted to talk about?

Just that we're not just looking for visibility here. We're not looking for a moment where we say Sandra Bland's name and then move on. I think that her mom last summer made a really clear call at the launch of the congressional black women's caucus, for action. She said, "I'm tired of hearing talk, I want to see action." And I think, today particularly, as I'm thinking of the arrest that shattered this chain reaction of events that led to her death, I'm just really moved again by that call to do something, and doing something requires us to rethink — not just our analysis and our framework, but also our organizing strategies, the things that we organize around, how we lift up different experiences while we're doing that organizing, and what kinds of things we're demanding and if those things are both gender-specific and gender-inclusive. It's not, and as you're saying, divisive to say, "We have to pay attention to police sexual violence as well as police physical violence." In fact, it helps us to see that even cisgender, non-queer men experience police sexual violence. And if we start talking about it, it's gonna lead to bigger liberation for all of us.

Andrea J. Ritchie is a Black lesbian immigrant and police-misconduct attorney, and a 2014 Senior Soros Justice Fellow, with more than two decades of experience advocating against police violence and the criminalization of women and LGBTQ people of color. She is currently Researcher-in-Residence on Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Criminalization at the Barnard Center for Research on Women and the coauthor of Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women (AAPF, 2015) and Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States (Beacon, 2011). She lives in Brooklyn, New York, and Chicago.

Follow Andrea on Twitter @dreanyc123 and find tweets on Invisible No More @InvisibleNMBook.