“I forgave my mother by understanding her.”

Being defined by a mother’s pejorative observations and pronouncements is deadly for a growing child’s self-esteem.

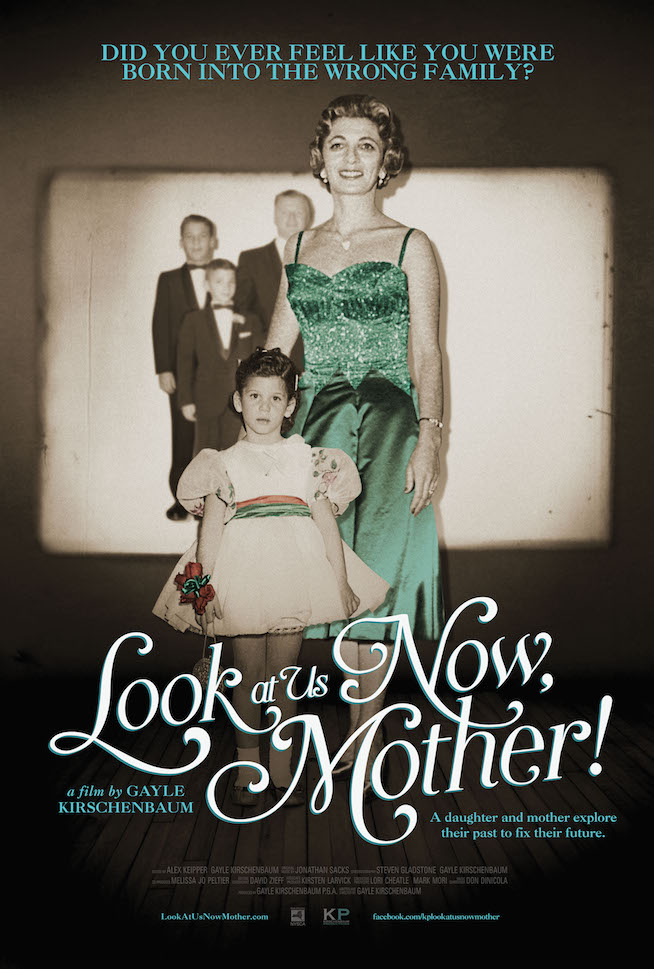

Filmmaker Gayle Kirschenbaum has added a new contribution to the material on this topic. Look At Us Now, Mother! is an exploration of coming to terms with her complex emotions and beliefs about her mother.

Mother (otherwise known as Mildred) is presented to the audience in all of her abrasive glory. At the beginning of the shoot, she was 87. Currently, Mildred is 92, and enjoying her new-found notoriety as she and Gayle do talk-backs after screenings.

Gayle introduces the narrative with the words, “This story may resemble yours.” Before we get to see her mother in action, she also informs the viewer, “This is a story about forgiveness.”

Mildred comes across as hypercritical, rejecting, and dismissive — keywords in the mother-daughter psychological lexicon for dysfunctionality.

We get to hear the top retorts she throws at Gayle, including the size of her nose, her unmarried status, and that her vocal inflections are too ethnically Jewish.

Gayle juxtaposes this harshness with images of the handmade cards she made for her mother, filled with love. She considers why she perceived herself as an interloper in her family.

By the age of 9, Gayle questions if perhaps she was adopted. It’s clear that her mother treats her male siblings much better.

Anecdotes recall humiliations at the hands of her mother, as well as controlling behavior and routine mortification. When recounting that Mildred didn’t like that Gayle was flat-chested at 15, we learn how Mom stuffed her daughter’s bathing suit top with foam. It escaped and floated away during a swim lesson. Rather than express regret at the incident, Mildred offers the response, “Your boobs grew, and your nose grew.”

Can it get any worse?

Yes, and it does — until Gayle decides she needs to heal herself and take her mother along on the journey with her.

Gayle convinces Mildred to do talk therapy with her under the guidance of several expert practitioners. Mildred is initially reluctant to go down that path; beginning sessions find her responding to her part in the relationship with either accusations (“You were always defiant. She was a bitchy little girl.”) or defensiveness (“I don’t know what I did wrong.”).

Probing into Mildred’s memories of her family of origin are stonewalled with repeated refrains of “I don’t remember” or “I don’t know.”

It takes time, but as Mildred starts to share memories of her upbringing, one can clearly see how she was damaged as a child and how those traumas impacted and shaped her mothering.

Poverty, a baby sister who died when Mildred was only 6, and a father who attempted suicide twice have led Mildred to use avoidance as a coping strategy.

Like other women who came of age during that era, Mildred had ambitions that went unfulfilled. She had talent as a musician, and aspirations to attend college to become a lawyer. That fell by the wayside when she pragmatically took an office job to earn a living. Her boss saw her aptitudes, and put her in sales. Mildred married at 18, before her husband shipped out for World War II. When he returned, he told her that her working days were over.

Gayle’s father also had unresolved anger issues about the way he was reared. Although we see her parents interacting contentiously, there is a balancing segment that reveals them as young sweethearts, through the letters they exchanged during the war.

The film is Gayle’s undertaking to get to the bottom of her family’s dynamics, and why her mother had such enmity towards her. “What went wrong?” she asks.

Like a flower opening its petals in an accelerated time frame, we watch therapy sessions as Mildred’s carefully built façade begins to crumble. Gayle is determined to connect, despite all the verbal invective Mildred throws at her. Defensive, Mildred tells Gayle that she is “abusive,” and notes bitterly that anything that happened “was [her] fault.”

As mother and daughter finally get into a space where recriminations are left aside, they begin to mutually mine the deepest emotional muck. Gayle’s epiphany is that the way to best understand and come to terms with her mother is to try to comprehend what shaped her.

“You matter deeply to one another,” one therapist states earnestly. “And there’s this missing piece that you’re so hungry for.”

It takes time, but with persistence, Mildred is enabled through therapy to cross the bridge of denial to acknowledge her shortcomings as a mother and ask for her daughter’s forgiveness.

It’s a hopeful and satisfying moment.

I spoke to Gayle about her aspirations for the movie and her quest to bring healing to others.

It's ironic that your father tracked you growing up with his own filmmaking via an 8mm camera. Do you see this inclusion of footage as his indirect contribution to the story?

Yes, I do. In fact, I thank him at the end of the film for the footage.

I also see a parallel between my Dad and myself. We both have documented our life and family. He was much more organized than me. He wrote on the back of each photograph the date, place, and people in the pictures.

You mentioned that when you screened the movie, it opened up a venue of communication for others to express their painful experiences. Although your story is specifically Jewish, hasn't it transcended ethnic boundaries?

Yes! All the awards we won were at non-Jewish [film] festivals.

I have been approached by people of all colors, races, and genders telling me how much my film relates to their story. An Indian woman, who was at a Jewish film festival in the United Kingdom, grabbed the mic after a Jewish woman said she thought it was a typical Jewish mother/daughter story. She said that she was Indian, and her mother gave birth to three daughters and only wanted a son when she gave birth to her and her twin sister.

She proceeded to talk about her childhood from hell.

What is your goal for the film?

To help people, and use this film as the centerpiece of a movement focused on forgiveness and healing between mothers and daughters.

So many people are in pain due to childhood trauma. It is so important to forgive. I teach people in my seminars how to do that.

You have stated, "The biggest gift you can give yourself is to forgive." It seems that you and your mother are now at peace with each other. How can other daughters learn from your example?

I forgave my mother by understanding her.

I did that by digging into her past and learning about what she suffered and endured in her own childhood. Then I was able to re-frame how I looked at her — from being my mother who should love and adore me — to a wounded child who did the best she could.

When she would send out a zinger again, it was listening to a child knowing she was really hurting herself, and not by reacting with anger or cowering.

Eventually, by giving her love, I rendered her abuse powerless over me.

Header image: Tina Buckman.

![Photo By Dr. François S. Clemmons [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Mr.%2520Rogers%2520%25281%2529.png?itok=LLdrwTAP)