It’s really goddamn hard to be a sexually empowered woman in our society.

From the idiotic and violent quotes about rape that conservative commentators and politicians spew continuously, to campuses and the broader criminal justice system failing sexual assault survivors, to the systemic targeting and release of female celebrity nude pictures, the deluge of negative ideas and attacks women face daily creates a persistent noxious white noise.

So thank the higher powers for Jaclyn Friedman.

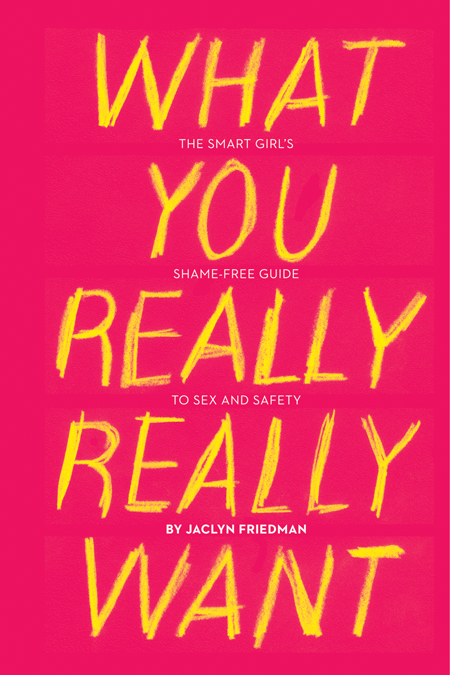

A noted writer, performer and activist, Friedman has been blessing us with her bravery and brilliance for years. In 2009 she co-edited the much-acclaimed Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape, which she followed up with What You Really Really Want: The Smart Girl’s Shame-Free Guide to Sex & Safety in 2011.

Not to mention her landmark essays—“F*cking While Feminist” and the highly personal “My Sluthood, Myself”—which emboldened thousands of women everywhere to embrace a more empowered sexual identity.

Friedman's also a celebrated speaker who's appeared on programs such as the Melissa Harris-Perry Show and on college campuses across the nation. Her writing has graced CNN, The Washington Post, The Nation, among numerous other outlets.

Oh, and she also founded Women, Action, & the Media (WAM!), a “people-powered independent nonprofit dedicated to building a robust, effective, inclusive movement for gender justice in media.” And hosts the Fucking While Feminist Podcast.

Fortunately for us, she still had time to talk to fill us in on her activist work, how she definies a healthier sexuality, the book-writing process, and how she stays inspired despite all the haters and trolls.

Can you talk a little bit about how you got involved in feminism and what has inspired your activism?

Feminism as an attitude has always just seemed natural to me. Maybe that's because I come from a long line of opinionated women who get stuff done. Maybe it's because my rabbi growing up was Sally Priesand, the first woman ordained in the modern era and a total feminist trailblazer. Maybe I was just born this way. I don’t know. It just always seemed obvious to me, long before I ever knew or thought about the word 'feminism.'

I've never really accepted the status quo as-is. I asked 'why' so much as a kid that my mother would eventually just say 'because Y is a crooked letter.' In the beginning of high school, when I got involved with the Reform Jewish youth movement, those questioning tendencies found a home in a social justice framework based in Tikkun Olam, the Jewish approach to 'repairing the world.' That’s probably where I got my start as an activist.

But it wasn't until college that I really understood myself as a feminist. I was a psychology major, and took a psychology of women class that broke a lot of things open for me. Around the same time, I went to see Jean Kilbourne present her legendary slideshow on the use of women’s bodies in advertising. There are a few moments in your life where you can feel things shift, where you walk in seeing the world one way, and you walk out seeing things irrevocably differently. That was one of them.

So I was already a feminist activist before I was sexually assaulted my junior year of college. But as you might imagine, that experience greatly radicalized and focused my efforts. One of the main ways I took my power back was through anti-rape activism on campus. And I’ve been at it ever since.

Have your feminist views evolved at all—and if so, how?

I think, as I've gotten older, my feminism has become more complex. How could it not be, after being exposed to so many wildly different people as my life has unfolded? 'Intersectional' is such a buzzword, but it really does mean something, which is that people don’t experience gender in a vacuum. They’re also experiencing class forces and racism and ageism and any number of other forces at the same time, and those aren’t severable. I try to ground my feminism in thinking about real people, so I've become less interested in ideological litmus tests or holier-than-thou politics, and more interested in practical outcomes—are things changing? For whom and how? I want my feminism to make actual women’s lives better; ideally, I want it to improve the lives of the women who are least likely to be helped by mainstream systems.

Much of your work involves constructing a 'healthy sexuality'—can you describe what that looks like? What does it mean to be 'sex-positive'?

Healthy sexuality looks very different on different people, because ultimately, it means nobody’s shaming or threatening you over your sexual choices. You have access to all the information and resources you need around sex and reproductive health, and you get to run your own agenda for your sex life as long as you don’t trample anyone else’s agenda. That can look infinity-different ways, because we’re all special snowflakes, and that’s what makes life (and sex!) fun.

As for 'sex-positive,' it's not a term I identify with or find useful. Sex isn't positive for everyone all the time, so the phrase itself can be alienating when people encounter it. The 'sex-positive' umbrella, while it includes some people whose work I greatly admire, also covers up too much oversimplified cheerleading that erases people's complex lived experiences and oppressions. Instead, I identify as a sexual liberationist, or a sexual justice activist, working for equal sexual freedom for all of us, no matter how we each feel about sex.

You've been involved in two book projects—Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape and What You Really Really Want: The Smart Girl's Shame-Free Guide to Sex & Safety (both of which I found totally inspirational, by the way). Can you talk a bit about the origins of these books and what the working-on-a-book process is like?

The process of the two books couldn't have been more different. Yes Means Yes was born in a hotel room late at night, at a party during a WAM! conference. I was hanging out with Jessica Valenti, and I had just published an article about how to connect the dots between alcohol and rape without victim blaming, and Jess and I got to talking about it and how it had been a while since Transforming a Rape Culture came out (which had had a huge impact on both of us), and how we'd been reading so many great people moving thought forward on rape and the sexual culture and enthusiastic consent, and we just worked our way into thinking, hey, we should do an anthology. So we brought it to Seal Press, where Jess had already published, and, well, you know how the story turns out.

Working on that book was a lot of fun. Reading submissions from brilliant writers both known and unknown, working with the writers we selected, really sinking our teeth into both the process of making each essay sing, and making sure the book felt like a complete whole—it was like nothing I've done before or since. And I gained a lot of appreciation for people who are editors for a living. Writing and editing: two very different skills, and we need them both. It also felt really free, in a way, because we never imagined it would blow up the way it did. We thought: Well, if this book influences some thought on the left in some small way, eventually maybe that will translate out into the larger culture. We never expected to be on Publishers Weekly's Top 100 Books of the Year list, or anything like it. So we really made the book we wanted, without thinking much about what would sell or how it would be received in the marketplace. We just worked from the heart. You don't often get to have such a pure process, and I know now how special it was.

The idea for What You Really Really Want came to me when I was touring in support of Yes Means Yes. I kept hearing the same question in different forms, from interviewers, young women at the book events, everywhere I went. It was some version of: I love the idea of yes means yes, of enthusiastic consent, but how do I know what I even want to say yes to? How can I tell what I want and don't want when everything in the culture is designed to decide for me? The repetition of that basic question made me realize a couple of things. One was that it was no accident that women are separated from our sexual agency. The anxiety caused by keeping women alienated from our own sexuality is instrumental in women's oppression. The second was: I knew how to answer the question. Or how to help women answer it for themselves, rather.

Still, I was a little unsure at first. I'm not generally a fan of self-help books, because most self-help books say, basically, that the reader is broken, and this book will fix them. So I made sure that this one is different. What You Really Really Want says: There's nothing wrong with you. The culture is broken. But here's how to best navigate that broken and undermining culture in a way that will feel most whole and authentic to you.

The process was terrifying. I've been a writer since I was maybe 10 years old, and I have a MFA in creative writing. But I'm a poet by training. I'm used to writing 100 words, and spending days and weeks and sometimes months making sure those 100 words are the exact right words in the exact right order and arrangement on the page. To write 80,000, 90,000 words? It seemed impossible at first.

What really helped was the group I formed to help test the exercises. I was developing some exercises for the book that I'd never run with people before, and I wanted to make sure they worked as intended; that they were clear, easy to do and effective. So I put out a call for volunteers, and wound up with a group of 12 incredible women from a real range of experiences and identities who read each chapter in draft form and did all the exercises. We would meet every Sunday afternoon on a conference call and talk about how that chapter had worked for them, what they had got out of it, what they wished had been different, etc. They shaped the book so much more than I even anticipated. Listening to them engage with the ideas in the book inspired two chapters that I hadn't originally planned, and their voices are all throughout the book, so that folks who pick it up who don't have their own group to talk things through with have some community along the way. They were just incredible. I’m still friends with several of them to this day. Plus, it was the perfect cure for writers' block; I had to get them a fresh chapter every week, or I was wasting their time. It forced me to just get words down on the page.

You helped found the organization WAM! (Women, Action & the Media). What inspired the organization, and what are its goals?

I founded WAM! because we can’t change the culture without changing the media that shapes it. At every level—access to media, representation, employment in and ownership of media—women are at a disadvantage. So we’re building a movement to change that, with live events via our volunteer-run chapters across the U.S. and Canada, online organizing, and direct actions—like our #FBrape campaign last year, which convinced Facebook to treat content that promotes or makes light of violence against women as hate speech.

So you write and talk a bunch about 'fucking while feminist'—you even have a podcast by that very name! What is it like to discuss your sex life in such detail so publicly?

It's messy! I decided to share personal details because people respond to first-person stories at a deeper level than they respond to philosophical arguments or data. And telling my own stories is a way to model what a lack of shame about sex can look like. But it's weird sometimes, having these things out there for anyone to find. When I was dating, sometimes my dates would Google me before we even met, and they'd know waaaaayyy more about me right out of the gate than I knew about them. That’s to say nothing of the prospect of my family or my partner's family knowing intimate details about my sex life, or the awkward moment when I'm doing an interview about something I consider unrelated and I'm suddenly on the spot about some sex detail I've shared.

It also involves, as you might imagine, a good deal of negotiation with my partner, because sharing details about my sex life sometimes means I have to share details about his. I’m lucky, because he’s incredibly supportive of my work, and we’ve managed to find a balance that works for us. But it’s something I want to be constantly mindful of. I may have signed up for this kind of life, but my current and former partners sure haven’t.

How are people's expectations about what you'll be like in bed informed by your feminist activism?

New lovers who make assumptions about me based on my feminism jump to one of two conclusions: either that I'm literally down for anything, or that I'm uptight, fragile and easily offended. Of course, like most people, I'm a lot more complex than either of those extremes. The folks who are more interested in me as a person than as a type are the ones who are lucky enough to find out exactly what I mean by that.

How do you deal with the trolls and haters? What keeps you inspired?

You have to have a plan. I’ve invested a lot of time and expense in making sure my private info is hard to access, and I've built myself a team of friends and loved ones that steps up when I'm getting attacked—one person filters the hate mail so I don't have to read it, taking care to flag anything that needs reporting to authorities or is otherwise exceptional. Another handles my social media. Someone else is on hand for emotional support. I self-block certain sites so I don't give in to the temptation to read the comments. It's pretty orderly at this point. But that doesn't mean it doesn't take something out of me. Of course it does. There are days you have to just go to bed and hide and rest and talk to friends, do whatever self-care means in that moment. And then when you're ready, you get back out there. There’s no shame in taking breaks and regrouping. It's a marathon, not a sprint.

But there's a big difference between online harassment and people coming at you with criticism you need to hear. It's hard sometimes to build up a thick enough skin that you can deal with the hatemongers while still staying open to hear from folks who could be your allies who are occasionally angry with you, and who don't always put it politely. I struggle with that a lot, because it's important to me not to be so well-defended that I don't hear the challenges I really need to hear. I don't always get it right. None of us are perfect. But I work really hard to do my best to listen through anger. Is there a point in there I need to hear, even if I don't respond well to how the message is delivered? It's my job to try my best to hear it.

But I'll be real: The critics aren't what keep me inspired. I'm not a saint. I'm inspired right now by Emma Sulkowicz, who's carrying her mattress everywhere she goes on her campus at Columbia until the university expels her rapist. It's not just her bravery, and her determination—it's her imagination, too. Her belief in what’s possible. Just incredible. I'm inspired, of course, by all of the student activists I get to work with when they invite me to their campuses, and by my colleagues. I'm inspired by my nieces and nephews—it's corny, but I really do want them to inherit a better world than I did. I’m inspired when I get email from people who’ve read my writing or heard my podcast or saw me at a talk, and have taken the time to let me know that my work has helped them in some way. I’m inspired by the poster by the artist Favianna Rodriguez that’s on the wall in my office—her work reminds me that I can be playful, beautiful and confrontational all at the same time. I’m inspired by the fact that mainstream outlets like Cosmopolitan, GQ and even Playboy seem to be embracing a few feminist ideas of late. What inspires me most of all is hope and the possibility of change. There's always a new approach to try; some possibility opening up that didn't exist before. I am fueled by optimism and anger in equal measures.

Any words of wisdom for aspiring feminist activists/writers?

Here’s the advice I give everyone who wants to change the world. It’s an old Jewish teaching by Rabbi Tarfon, and it loosely translates to “It is not yours to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.” None of us can fix the world by ourselves. All we can each do is our own small piece of the work. Figure out what you want to contribute, collaborate with others who are working on their pieces as well, and take it one day at a time. That’s the only way change happens.

You recently announced that you're stepping down as executive director of WAM! What's up next for you? And where/how can we follow it?

I'm hoping to be writing a new book soon! I'm working on the proposal now, so I can’t say much more just yet. And I'll be keeping on with my podcast, Fucking While Feminist, and I’m sure I’ll be taking on short-term projects as well. The best way to keep up with all of it is at my website, jaclynfriedman.com, or by following me on Facebook and Twitter @jaclynf.