...we know empirically that fat discrimination can shorten people’s lives and decreases cardiovascular health.

A few months ago I was asked to give a talk to a group of undergraduate kinesiology students.

I will admit right now that I was intimidated.

Kinesiology undergrads are not my usual crowd. I did my Master’s research on fat women of color queer femininity. I’m a women’s studies, critical culture studies kind of lady. I’m used to giving talks to people whose primary academic interest is deconstructing sexism, hegemony, and racism and who hold workshops on how to spotlight microaggressions, organize clothing swaps, and otherwise subvert capitalism.

Maybe it was unfair of me to assume that these students were not invested in the aforementioned endeavors. Regardless of my preconceived notions of them, I placed them firmly outside “my base.” “Isn’t kinesiology the academic arm of the gym industry?” I asked a friend nervously.

Health is the banner we have raised in defense of weight loss surgery, The Biggest Loser, putting children on diets, shaming our friends and family members, fat jokes, weight-based workplace discrimination, and heavily processed low-calorie meals with no nutritional value.

I imagined myself dressed in one of my not-really-but-kinda-trying-to-look-respectable lecture outfits — maybe a white button-down with a bright pink business skirt or a black dress with an enormous rhinestone-covered lobster necklace. In this scenario, I walk nervously into a room filled with White dudes who wear tube socks, chew gum, and are wearing tiny amounts of white clothing that showcase their muscles. They are all judging me because I am a lady, and a fat one. What could I teach these hunks who embodied the American ideal of fitness?

When I talked to the professor, he forecasted my fears, telling me that a lot of people think his students are going to be jocks with closed minds. In fact, he said, they were open-minded and curious, and that he had personally dedicated a lot of time to encouraging them to think critically about the messages we receive about health.

“Would it be OK if I did an exercise at the beginning where I ask them to define health?” I asked him. He gave the OK, and then I talked with Jacob (my boyfriend) about the particulars. How should I word the question? How much time should I give them? Am I secretly doing this to prove that even burgeoning experts in fitness have no idea what health is?

My question stemmed from a suspicion or maybe a theory. What I’ve found so interesting is the prevalence of the word “health” in the conversations on fatness and fat people. We as a nation are obsessed with being “healthy.”

Health is the banner we have raised in defense of weight loss surgery, The Biggest Loser, putting children on diets, shaming our friends and family members, fat jokes, weight-based workplace discrimination, and heavily processed low-calorie meals with no nutritional value. This word is used to sell food, gym equipment, blenders, and public policy. I hear it bandied about daily, and yet what do people mean when they use that word? Are we all talking about the same thing? And if we’re not, then how can we be such enthusiastic proponents of an elusive idea?

How can we be waging a government-sanctioned war against fat people and fat kids, spending billions of dollars on the diet industry, and bullying people based on an idea we can only vaguely identify?

So I decide to test my theory. I thought: If anyone can define health, it’s people who are in school studying that very thing. I asked the students to put away their phones and laptops, to take out a pen and to write down (on the slip of paper I had given them) the definition of heath.

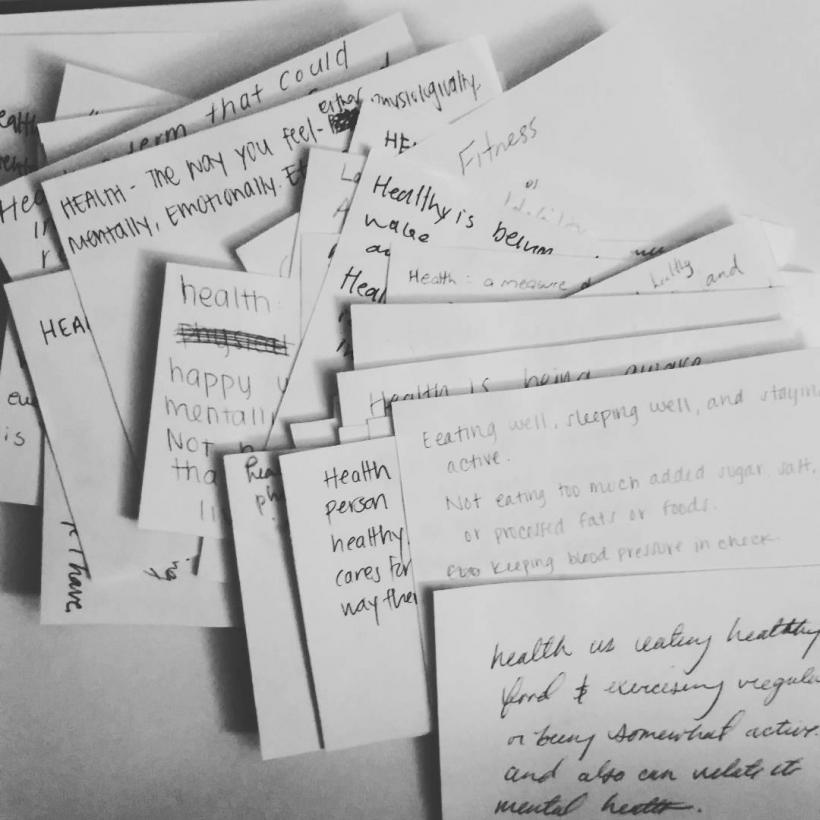

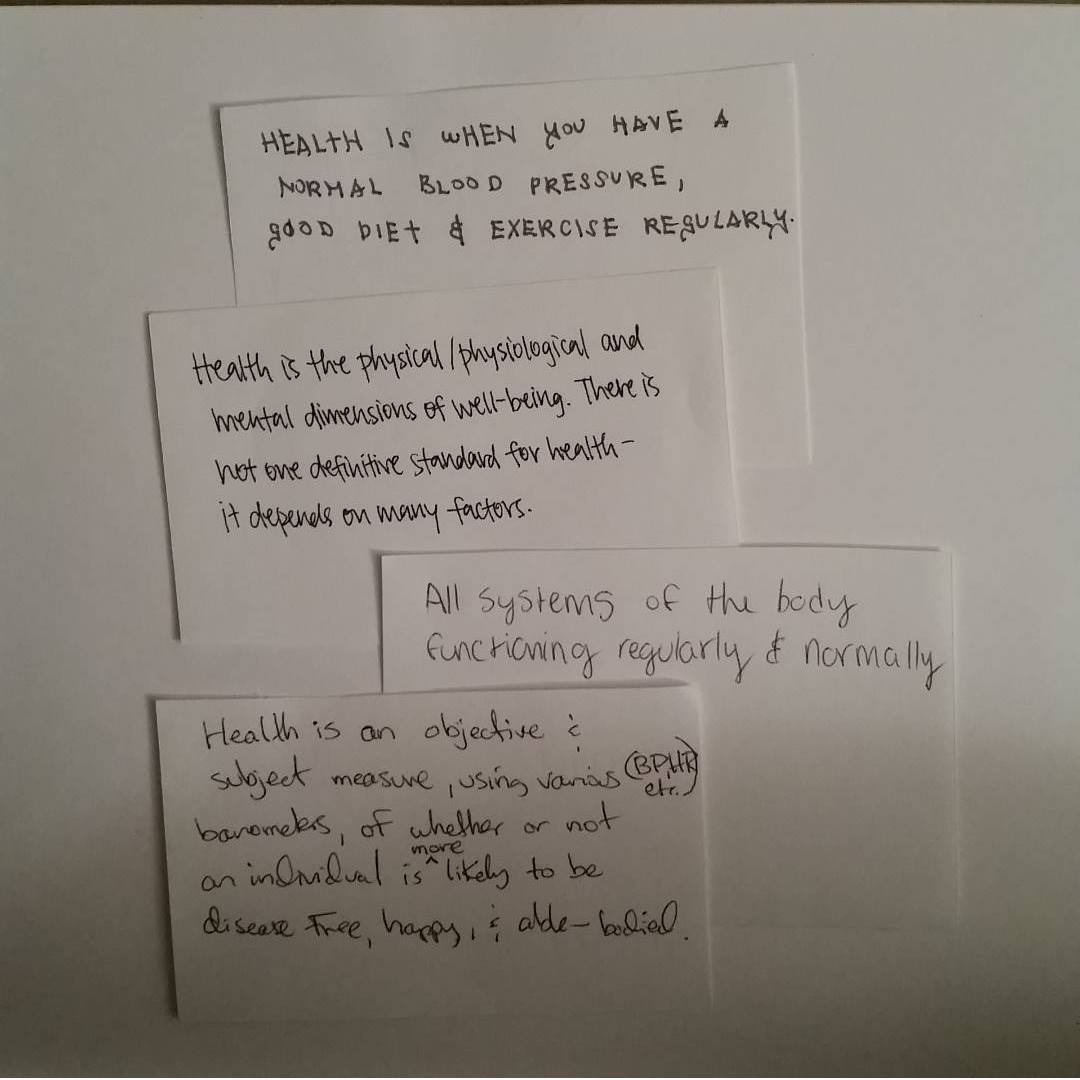

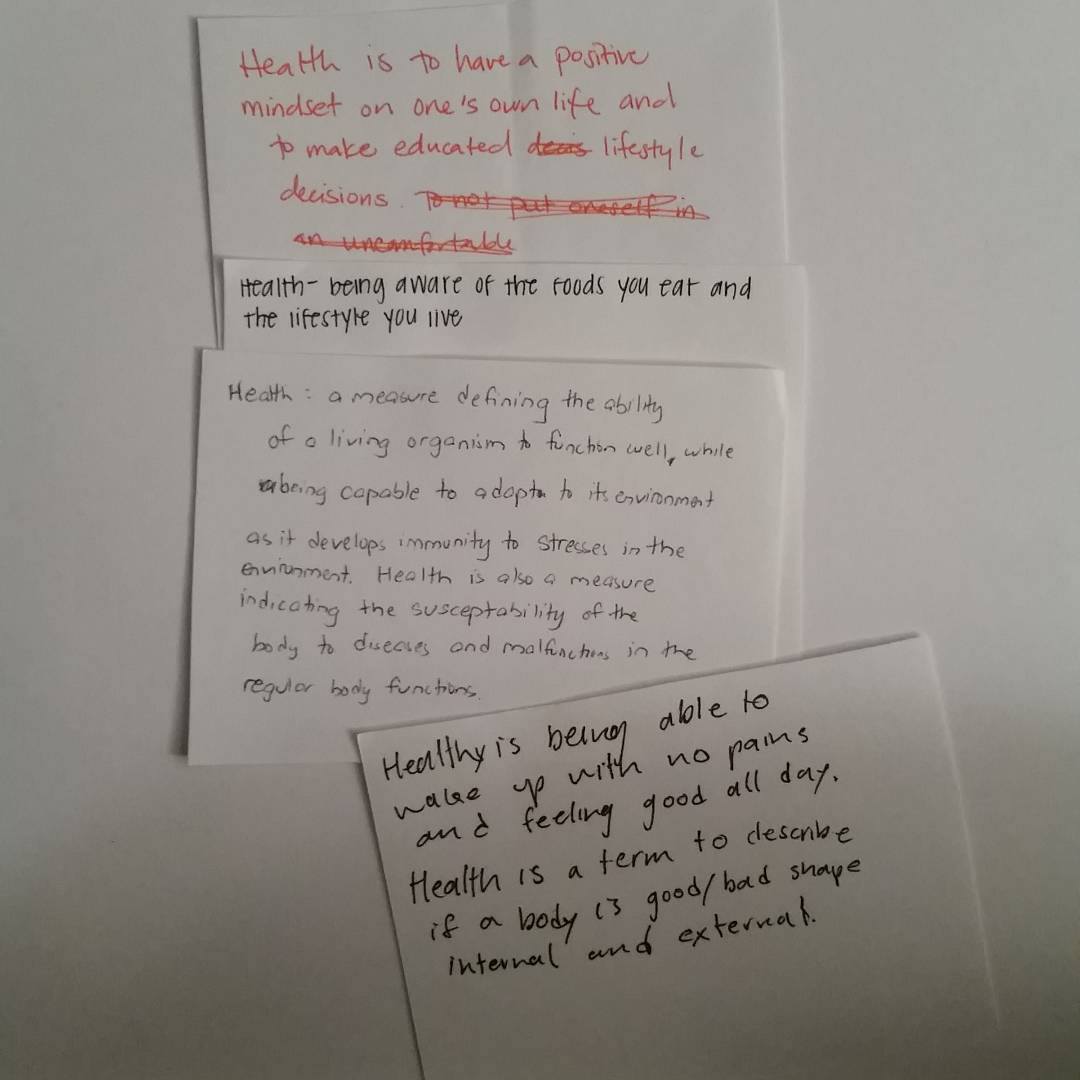

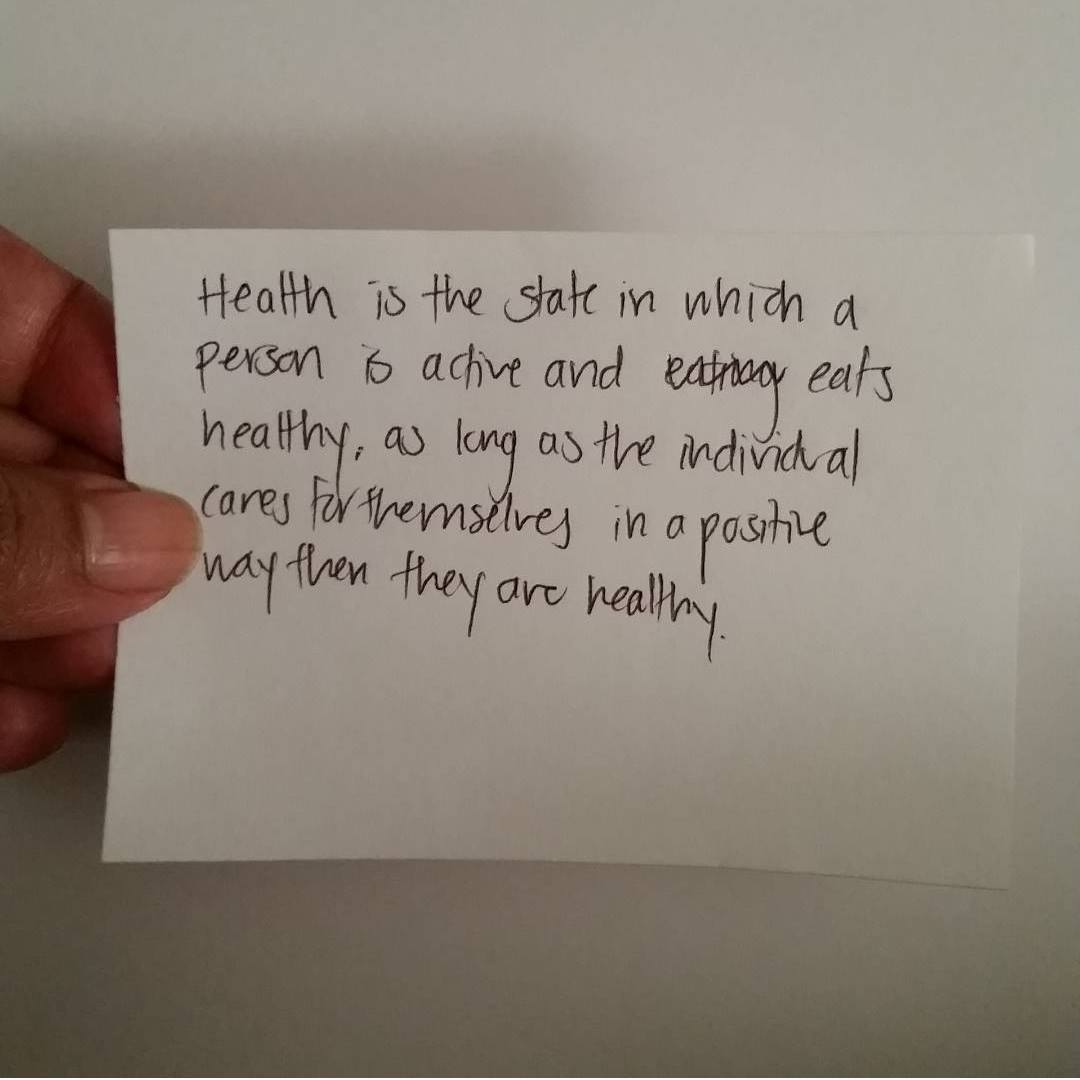

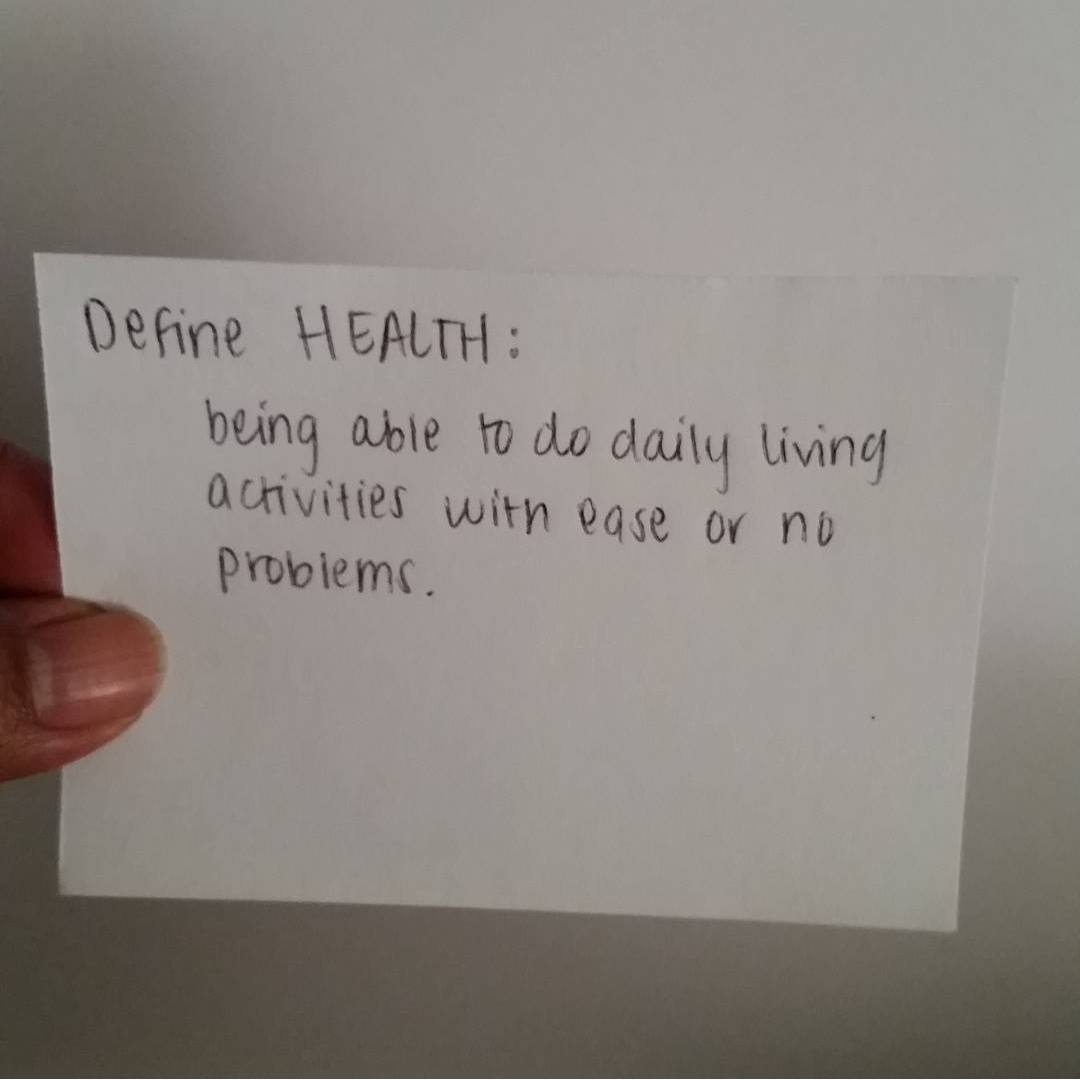

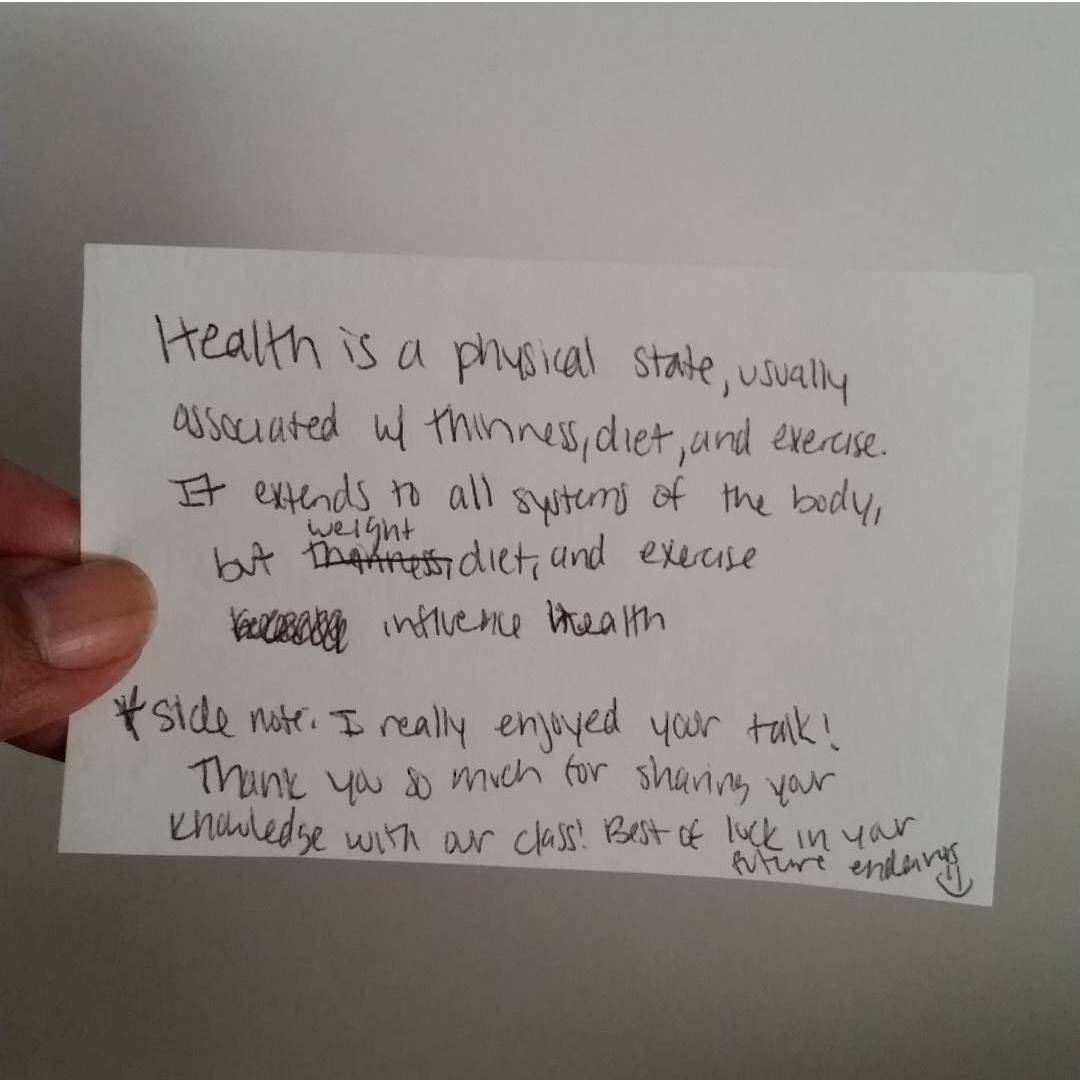

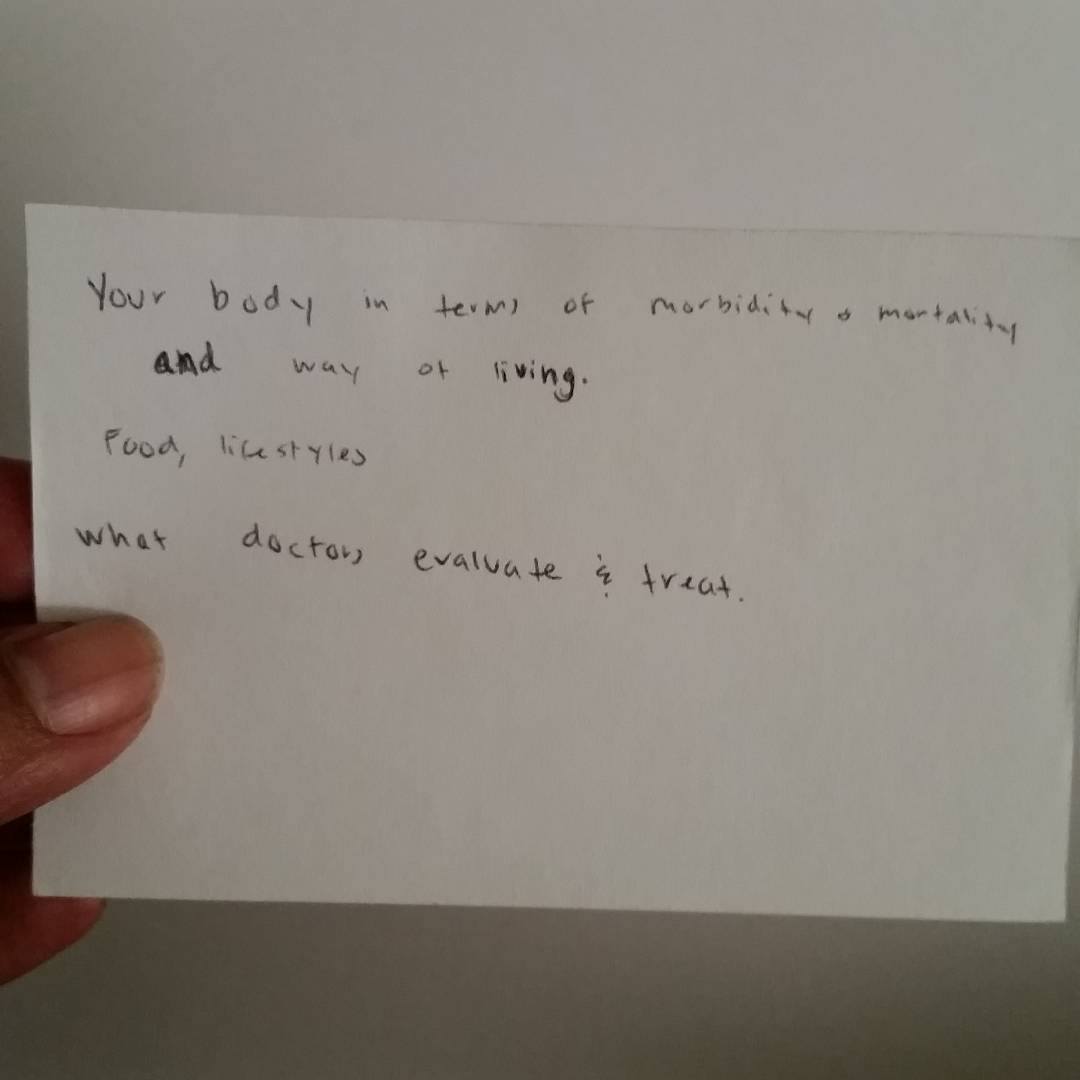

Here are some of the things they wrote (I randomly chose the responses I photographed):

After they were done, I asked some volunteers to read the definitions out loud.

As they read them, I was struck by the thoroughness and thoughtfulness of their words. And I also noticed how different each student’s definition was from the next.

After the class I started sorting the responses by theme (because I’m a total nerd). I looked to make sure I wasn’t being hasty in my assessment. Maybe they didn’t use the exact same language, but perhaps they were all essentially saying the same thing? In fact, no. I found the absolute smallest number of piles of thematically-similar definitions I could reduce them to was — ready? — nine. Nine definitions of health in a pool of 60 responses.

Some of them said health was subjective, others said it was objective. Some definitions said that health was a thing that doctors determined. Some were primarily interested in weight as a measure of health. Others felt mental well-being was the most important component of a healthy life. Some definitions included metrics like blood pressure or BMI, while others talked about the presence or absence of pain as indicators.

You can see in their writing that there is exertion in defining the word health — the crossed out words, the carets that indicate afterthoughts, the words crowded at the edges of the paper stuffed into parentheses.

I think it’s important to tell you that, in general, when asked to define a word in a limited amount of time, people do all these things. It’s hard to define things. These students were just like most of us given this task. The important difference is that they weren’t asked to define something obscure. They were asked to define something that we as a nation almost unanimously feel is a demand we are allowed to make of all citizens. They were asked to define something that we should probably all be on the same page about if we’re going to be throwing a lot of money and energy at it, right?

In my opinion, it is no accident that there is so much variation in their responses. I think the word “health” is code for other things. We use the one word to indicate our anxieties or offer our praise. And it’s a word that cuts both ways. We use it to laud upper middle class gym-goers who are “making sacrifices” and “exercising discipline,” things we as a nation have been obsessed with since, like, 1799. We use “health” to describe our expectation that everyone ought to be thin. We use that word to ostracize disabled people. We use that word to pathologize poor people. We use that word to justify fat-shaming.

When the truth is that we know empirically that fat discrimination can shorten people’s lives and decreases cardiovascular health.

The truth is that if we want to talk about a “healthy” diet, we’ve got to talk about the corn subsidies that allow high fructose corn syrup to be streamlined into nearly everything we eat.

The truth is that public health is achieved through diligently pursuing the measures we know promote mental and physical health, like ending homelessness, narrowing the gender divide, ending mass incarceration, ensuring environments free of known carcinogens, and single-payer healthcare.

We target individuals who are deemed unhealthy by visual assessment, and we say “you are the problem and I am allowed to stigmatize you because you do not fall into a single, arbitrary version of American success.”

It’s hard to get all that nuance onto one tiny, little piece of paper.

Make what you will of my theory, but the next time you’re with a group of people, I challenge you to try this experiment with them. And then — as you’re reading through the pile of, likely, very different responses they’ve come up with...ask them why, if health is so important, we can’t seem to define it.