A new book teaches girls about the women who've shaken up history. We got our hands on some excerpts.

Rebels, trailblazers, visionaries.

This is how Rad American Women A to Z, a new educational book for girls and young women, describes its 26 subjects—all of whom possess characteristics of all three.

From civil rights leaders to artists to athletes to a Supreme Court Justice, the women in the pages of this illustrated book are designed to inspire all those accustomed to history books that focus on powerful and important men (which is to say, all those accustomed to history books).

In promoting the book, City Lights publishers—which released the book on its 60th anniversary—pointed out that girls’ self-esteem begins to plummet as they approach puberty, and that boys also begin to learn to devalue the role of girls and women during this stage of their development. What better way to counter this than with a guide to history-making women? As Publisher and Executive Editor Elaine Katzenberger put it: "Kids can perceive the model for a better future for themselves in these stories, and the world definitely needs more rad women!”

We concur.

Check out some choice excerpts below, then order the book—featuring illustrations by Miriam Klein Stahl and text by Kate Schatz—here. (And yes, grown-ups are very much welcome. Couldn't we all use more rad women in our lives?)

Angela Davis: Who never backs down from the fight for justice

Angela Davis was born in 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama, into a neighborhood known as "Dynamite Hill" because a group of racist white men called the Ku Klux Klan often bombed the homes of black families who lived there.

Schools were segregated in Alabama back then, and the education that black children received was inferior by far. Despite those di°culties, Angela was a smart and curious child, and her parents were thrilled when she got a scholarship to a high school in New York City, where she could go to school safely and pursue her passion for learning.

Angela thrived in her new school, and she and her new friends attended rallies and protests in support of the Civil Rights movement, which demanded equal rights for black people in America. In college she was one of only three black students in her class. She felt isolated, but she didn't let that stop her from learning. Angela loved philosophy and literature, and she continued her college career in Europe, where she studied the writing of many great thinkers. She connected their ideas with her own beliefs about the injustice that she was witnessing.

She began speaking out against racism and sexism, and in favor of gay rights. She criticized the U.S. government for its role in the Vietnam War. In 1969 she was hired as a college professor, but the Governor of California had her fired because of her political beliefs. Her students and fellow teachers were outraged, and they rallied to support Angela. She didn't get that job back, but she went on to teach at several other prestigious universities, and she continued to speak out about injustice, wherever it occurred.

Today, Angela educates people about the unfair treatment of prisoners. She has written nine books, including a book about her own life. She is a powerful and inspiring public speaker, and people listen to Angela because she is a strong black woman who is never afraid to tell the truth, to speak her mind, and to demand justice and liberation for all people.

The Grimke Sisters: Who devoted their lives to the pursuit of freedom and equality for all

Angelina and Sarah Grimke were sisters who were born 12 years apart, but they were like twins when it came to their commitment to ending slavery.

In the early 1800s, the Grimke family lived in Charleston, South Carolina, on a fancy cotton plantation. Like most other rich white families in the South, the Grimkes owned slaves. The sisters saw their daily suering and knew it wasn’t right. Even though it was against the law, Angelina secretly taught one of their slaves to read. She and Sarah tried to convince their parents that slavery was wrong, but Mr. and Mrs. Grimke wouldn’t listen. So the girls made a hard but powerful decision: They said goodbye to their parents, their 11 siblings, and the fancy dresses and dances. Then they moved north to Philadelphia, where the anti-slavery movement was beginning.

The Grimke sisters joined the Quakers, a religious group dedicated to nonviolence, and they became abolitionists (people working to end slavery). They gave passionate speeches and wrote fiery letters in support of freedom for all people. They didn’t care if people tried to punish or persecute them for their convictions. “Emancipation,” Angelina wrote, “is a cause worth dying for!” The pro-slavery people were furious at the sisters, and some of their fellow Quakers were shocked that a woman should say such things. Some angry people even burned their articles and letters!

Not everyone was upset, though. Many people admired Sarah and Angelina. They traveled to more than 67 cities, giving speeches to mixed audiences of men and women, blacks and whites together. In their lectures they explained that the equality of women was connected to the freedom of black people. Again, people were outraged, because they had never heard white women express these kinds of ideas. Many abolitionist men failed to support equality for women, and many early feminists did not care about ending slavery. In 1838 Angelina became the the first American woman to speak in front of a legislative body when she presented anti-slavery petitions signed by 20,000 women to the Massachusetts Legislature. Sarah and Angelina lived and worked together for their entire lives, united in their belief that all human beings deserve freedom and equality.

Maya Lin: Who makes big ideas into beautiful art

Maya Lin’s parents came to America from China just before Maya was born. As a child she loved to play by herself, using her imagination as she explored nature and played in her dad’s ceramics studio.

Maya got straight A’s in school and excelled at math and science. She especially liked to build models of miniature towns, so it made sense when she decided to become an architect.

When Maya was still a student at Yale University, she entered a contest to design a memorial for the American soldiers who had died serving in the Vietnam War; it would be built in Washington, D.C., for all to see. Maya submitted her unique design, but didn’t think she would win. She was only 21 years old, after all, and her design was very different from the other grand memorials that had been constructed in the nation’s capital. The Vietnam War was very controversial, and Maya wanted her design to show that. Instead of a statue, Maya imagined a big, shiny wall covered in the names of soldiers. The wall would reflect the image of the person looking at it, like a mirror. That way, Maya thought, visitors would see themselves in the wall of names, and be reminded that war affects us all.

More than a thousand people entered the contest, and Maya—a college student—won! This upset some people, but Maya defended her design and refused to back down when several politicians demanded she change it. She believed in her work and saw it through—and now the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is one of the most frequently visited memorials in the United States.

That’s not all Maya has done. She continues to work as an artist, making giant sculptures inspired by natural landscapes and science. She is passionate about the environment, and sometimes she uses garbage and recycled materials, including her children’s old toys, to make art. She has also designed parks and other memorials, including the Civil Rights Monument in Montgomery, Alabama.

"Queen Bessie" Coleman: Who soared above discrimination

Bessie Coleman was 11 years old and living in Texas when the Wright Brothers completed the first successful airplane flight in 1903. She read stories about these flying machines, and she dreamed of soaring through the air herself.

Bessie’s family was very poor, and even though her mother didn’t know how to read, she encouraged her daughter to pursue an education. The one-room schoolhouse for African American children was four miles from their home, and on days when Bessie didn’t have to pick cotton in the field, she would walk all the way there and back. Despite her hardships, Bessie got good grades and was able to graduate.

As a teenager Bessie continued her hard work. She polished other people’s nails, washed their laundry, and served their food. She also listened to the tales that her brothers told her about the female pilots in France who flew planes in World War I. Then she read about Harriet Quimby, the first American woman to get a pilot’s license. That was that! Bessie decided she was going to be a pilot. She tried to enroll in aviation schools, but every one of them turned her down. No one would accept a black woman.

Did that stop Bessie from pursuing her dream? No way! She began taking French lessons and soon raised enough money to travel all the way to Paris, all by herself. There, she was finally accepted into a flying school. She was the only black woman, and even after she witnessed a fellow student’s terrible plane crash, she kept going. It took her seven months to learn how to fly a plane, and in 1921—two years before Amelia Earhart—she got her international pilot’s license.

Bessie continued to train as a stunt pilot, learning how to do crazy tricks like spins, dives, and loop-the-loops. This was called “barnstorming,” and Bessie excelled at these daring feats. She performed all over Europe, and back in the United States, too. People called her “Queen Bessie” because she was the best and bravest female pilot out there.

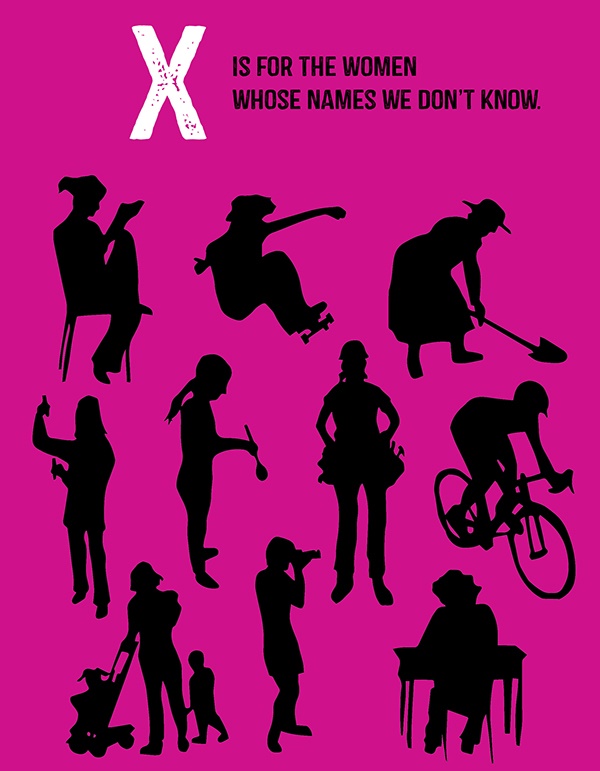

It’s for the women we haven’t learned about yet, and the women whose stories we will never read.

X is for the women whose voices weren’t heard.

For the women who aren’t in the history books or the Halls of Fame, or on postage stamps and coins.

For the women who didn’t get credit for their ideas and inventions.

Who couldn’t own property or sign their own names.

The women who weren’t taught to read or write but managed to communicate anyway. Who weren’t allowed to work but still supported their families, or who worked all day but weren’t paid as much as the men.

X is for the radical histories that didn’t get recorded.

X is for our mothers, our matriarchs, our ancestors.

The nurses and neighbors and aunties and teachers.

The women who made huge changes and the women who made dinner.

X is for the hands that built and shared and wrote and fought.

The bodies that birthed and worked and strained to keep going. The feet that walked, ran, jumped, and balanced.

The minds that dreamed and desired, the hearts that loved.

X is also for all that’s happening now and all that is still to come.

X is for the women in homes and offices and fields and labs and classrooms, who invent and transform and build and create.

X is for all we don’t know about the past, but X is also for the future.

X marks the spot where we stand today.

What will you do to make the world rad?