Every Saturday DoubleCakes writes about feminism and misogyny in the B movie genre. Read more film reviews—like Freaky Fridays!—right here.

As a child, I was sent to my room a lot, and seven years separated from that house hasn't helped me unlearn an association with involuntary detainment. I don't like being in my bedroom. I eat standing up in the kitchen, I do my writing sprawled out on the living room floor. For me, a bedroom is for sex, ukulele playing and other things not acceptable to do in front of your roommates—but if I ever live alone it won't even be for that.

I always take up a friend's offer to see their bedroom, even if it's just to tag along while they rummage through dirty laundry for their wallet. It's interesting, I guess in the same way it's "interesting" to watch a dude chainsaw a bear out of ice blocks or some other talent that is beyond your imagined potential, to see how other women make their rooms into sanctuaries.

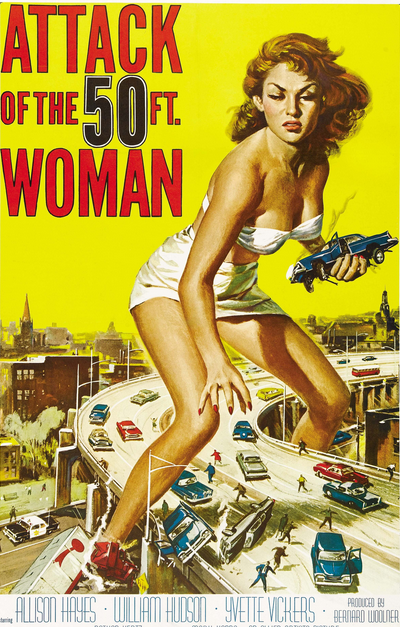

Many of my friends who have posters for "Attack of the 50 Foot Woman" have never seen it, but relate to it regardless. I think it's the sneer. Director Cecil DeMille is telling us to smile even though it's been a long day walking down that sidewalk. Just like yesterday. Just like tomorrow. That sneer, just looming, like flying saucers over Hollywood, is an encouragement.

Just you watch. One day I will destroy you all.

When I began transitioning, I rented a lot of Marilyn Monroe movies. I learned the songs and practiced my walk in empty Wal-Mart aisles. I thought if I applied myself to pageantry than I could be accepted as a woman on the grounds of my enthusiasm. Given an "F" for effort. But a single gaze upon Nancy Archer's malevolent intentions (yes, she'd be the 50-foot woman) taught me more about being a woman than any charm school syllabus (though I still warmly harbor the fantasy). Allison Hayes' face taught me much about the role of defiance in womanhood.

The term "gaslighting" comes to us by way of a 1938 play, adapted to a 1944 film starring Ingrid Bergman. The film ends with Ingrid tying Charles Boyer to a chair and teasing him about his inevitable execution—a cautionary tale.

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, released 14 years later, takes the cautionary tale into the "supersonic age," foregoing a cerebral edge in favor of murder and giantess fetish!

The film tells the story of Nancy Archer and a fireball careening over the planet Earth. Nancy, played by Allison Hayes, is wealthy enough that her estranged husband's mistress suggests having her murdered in the first three minutes of the film, sans any meaningful internal conflict or build-up.

Nancy has a drinking problem and a history of mental illness. This helps establish her as a bona fide B-movie protagonist and justifies the awful treatment she receives from just about every other character in the film, which in turn justifies her drinking and paranoia. Every woman is a time traveler in her own way.

Mrs. Archer encounters the aforementioned fireball while driving one night, and is in turn, greeted by the giant claw of a giant ghost alien. She abandons her car and runs into town, screaming, whereupon she is offered coffee by the local sheriff, asked about her drinking, and handed off to her resentful husband.

Everyone—and I mean everyone, the police, her butler, her doctor, random ass townfolk—knows that her husband is cheating on her and is only after her money. (But they would be the real monsters to let that come between this touching and kinda arousing scene of Harry helping her out of her clothes and into bed.)

The police don't find the fireball or the alien, even though it was in the news and this was back in the time when your local township only had one news source . . . they just assume Mrs. Archer is losing her mind.

Nancy eventually convinces Harry to go with her, back out into the desert, to find the alien. The film then violently veers into "documentary on gender relations" territory as Harry sees the alien, shoots it a bunch, and then runs away, leaving Nancy behind to the cruel whims of the monster.

In a touching rebuttal to the xenophobia of the 50's, the alien robs Nancy of her diamond necklace—which he needs to power his ship of course—but, now having seen how useless earth men are, gives her a lift back to her house.

She is found delirious and her doctor, who gets a saccharine monologue about his guilt over advising her to take Harry back. This allows us to ruminate on the implicit trust we give doctors, lawyers, and other people offered systemic power regardless of their actual capacity for giving advice. The doctor ends up sedating the shit out of her until he can figure out what to do.

Do you want giant women hell-bent on revenge to stomp the hell out of your city? Because this is how you get giant women hell-bent on revenge to stomp the hell out of your city.

Honey (Harry's mistress) played by singer and Playboy model Yvette Vickers, encourages Harry to sneak up on Nancy's unconscious body and murder her with lethal injection. Of course. Vicker's character is as callous and shallow as any 50's femme fatale caricature, but she gets my favorite line in all the film, and maybe all of 50's cinema.

The quote doesn't quite line up with the scene, but I think this makes a good motivational and delicately touches up on why I love 50's movies so much.

Most of the 50's monster movies that we consider the "old guard" or "classic" are like 80 percent menial talking. Your average budget just didn't allow for a two hour sprawling epic where the monster mingles with the locals for forty minutes while they sort out their motivations. Instead it's a long slow tease leading to a short but emphatic payoff; you get movies with flying saucers and disembodied heads that have at times heated debates on military interventionism, male entitlement, and the advantages of being sexually available to all genders.

Every person in Nancy's life fails her. While some are doing it on purpose, many are following the script as they read it, based on our societal attitudes towards the emotional health and stability of women. Everyone knows that Harry is a toxic influence on her, who openly cheats on her—but yet they bow to his status as her husband, and are even relieved to do so, because then she becomes his problem.

How she's solved becomes secondary.

Okay. Back to the action.

Harry finds that Nancy has grown huge and just nopes right out of there. A medical team splices the genes of several fetishes to create a very tantalizing tableau sure to keep the fetish message boards riled for ages: a giant naked woman kept comatose and chained to the bed.

The Sheriff and Nancy's Butler—arguably the people in the film to have failed her the least—discover the alien, who, now having learned how weak and ineffective earth men are, wrecks their ride and leaves them in the desert. (In a narrative sense, this affords these characters punishment for their wrong-doings, but concedes that they could done worse, and had far worse done to them as well.)

Oh, an important aside: a woman's jewelry figures heavily, in this film and Gaslight, as catalysts of plot and motivation. To take a woman's jewels is to in affect, kill a part of her. While effective symbolism, I think this betrays a deep-seated association with femininity and material wealth or affect. There are literally hundreds of films, novels, and games about stealing a woman's jewels. No one's ever made a movie about a man having his wristwatch stolen.

And at long last! Enough of the plot crap has transpired and now we can get to the dessert of our decadent taste for fantastic violence.

Nancy breaks out of her bed and tears through the city, looking for her husband. Even 56 years later, I find myself in a blissful state of awe watching this scene. Being tall, I find myself courted by the fears of smaller women—on the street, riding the bus. Women avoiding their exes hide behind me in bars and cast knowing looks on street corners when men try to touch their tattoos. I have never known smallness. To hold it, for even just a second, would exhilarate me.

But Harry and Honey are not me and are very unhappy about being murdered by a giant woman.

Nancy crushes Honey with a ceiling beam and carries Harry away. (I often tell people the film ends with her eating her philandering husband, in a coy attempt to get them to watch it.

Instead, the Sheriff, hands off to the very end, ends up shooting a transformer which blows up, killing her and Harry.

And keeping to form, the good Doctor, eyeing the fruits of the town's apathetic labors, tells us, "she finally got Harry to herself," serving his role as a respected voice in the community to make some sense of this carnage and dutifully misdiagnose Nancy as just being an obsessive crazy pants.

There's no limit to the damage of a woman's rage as long as some dude can step in and have the last word to wrap it up all nicely.

This film has been remade and parodied a number of times, but none have experienced the success of the original. I feel that as budget and technology allow us to put more emphasis on the "monster" part of the "monster movie," this flexing of movie magic muscle comes at the cost of space for social commentary (albeit delivered in deadpan). While terse dialog bemoaning social ills doesn't sell a lot of popcorn, it counts for a lot, in the long run.

And that sneer. That sneer counts for a lot too.

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)