Considered one of the rarest and strangest of all neurological disorders, Cotard's Syndrome is the nihilistic delusion that one is dead—a walking corpse.

While the mental illness is named after circa 1888 neurologist Jules Cotard, a case was documented nearly 100 years earlier in 1788 by Charles Bonnet.

"[T]he ‘dead woman’ became agitated and began to scold her friends vigorously for their negligence in not offering her this last service; and as they hesitated even longer, she became extremely impatient, and began to press her maid with threats to dress her as a dead person. Eventually everybody thought it was necessary to dress her like a corpse and to lay her out in order to calm her down. The old lady tried to make herself look as neat as possible, rearranging tucks and pins, inspecting the seam of her shroud, and was expressing dissatisfaction with the whiteness of her linen. In the end she fell asleep, and was then undressed and put into bed." — "Charles Bonnet’s Description of Cotard’s Delusion and Reduplicative Paramnesia in an Elderly Patient (1788)," British Journal of Psychiatry

Cotard went on to document the case of Mademoiselle X, describing her mental illness as Le délire des négations ("The Delirium of Negation"). Mademoiselle X vehemently believed she had "no brain, no nerves, no chest, no stomach, no intestines." She insisted she was "nothing more than a decomposing body," didn't need to eat, and couldn't die unless she was burned. Eventually she starved to death.

Researchers have discovered that among those suffering from Cotard's Syndrome, there is a high level of paradoxy. In 2007, a study took 100 patients suffering from varying degrees of Walking Corpse delusions and found that, "denial of self-existence is a symptom present in 69 percent of the cases of Cotard's syndrome; yet, paradoxically, 55 percent of the patients might present delusions of immortality."

Currently, Cotard’s syndrome is not classified as a separate disorder; nihilistic delusions are categorized as "mood congruent delusions within a depressive episode with psychotic features."

Graham Harrison might beg to differ, however. Following a suicide attempt nine years ago, Harrison woke up in the hospital and believed he was dead.

"When I was in hospital I kept on telling them that the tablets weren't going to do me any good 'cause my brain was dead. I lost my sense of smell and taste. I didn't need to eat, or speak, or do anything. I ended up spending time in the graveyard because that was the closest I could get to death." —NewScientist.com

Despite the fact that Graham recognized empirically that he was talking, breathing and decidedly alive, he couldn't accept it or reconcile his own truths; he truly believed he was dead.

"I just got annoyed. I didn't know how I could speak or do anything with no brain, but as far as I was concerned I hadn't got one . . . I lost my sense of smell and my sense of taste. There was no point in eating because I was dead. It was a waste of time speaking as I never had anything to say. I didn't even really have any thoughts. Everything was meaningless."

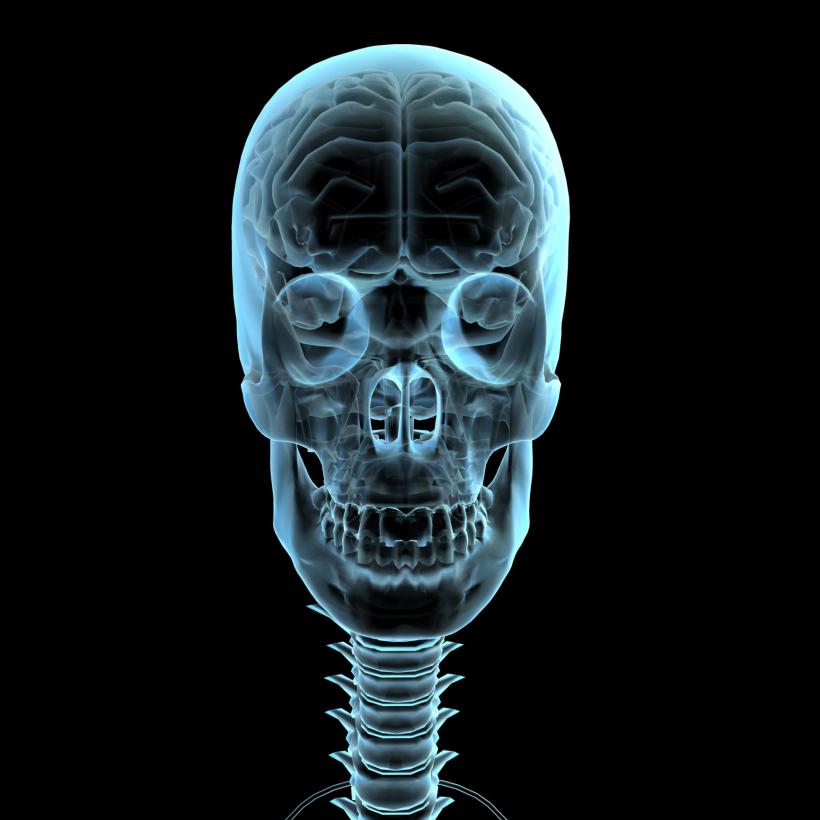

Finally he was taken to a team of neurologists who ran the first-ever PET (positron emission tomography) scan of someone suffering from Cotard's Syndrome. A PET uses a radioactive drug—known as a "tracer"—that is injected, swallowed or inhaled depending on which which organ or tissue is being studied. The tracer enables scientists to observe areas that have higher levels of chemical activity, which in turn, often correspond to areas of disease. These tell-tale areas appear as "bright spots."

What they found in Harrison's brain was nothing short of shocking. He was, actually, kind of dead. The metabolic activity in both his frontal and parietal brain regions was so low that it resembled that of someone in a vegetative state. Wilder still, but not-so-surprisingly, these areas of the brain are responsible for what scientists call the "default mode network," an intricate and still rather mysterious system of brain activity believed to be responsible for our sense of consciousness, recollections of the past, a notion of "self" and our theory of mind, basically enabling us to attribute certain mental states—from desire to pretending—to ourselves and others.

Harrison, through a lengthy dedication to therapy and medication, has recovered enough to live alone. But he still describes his headspace as, aptly, "bizarre."