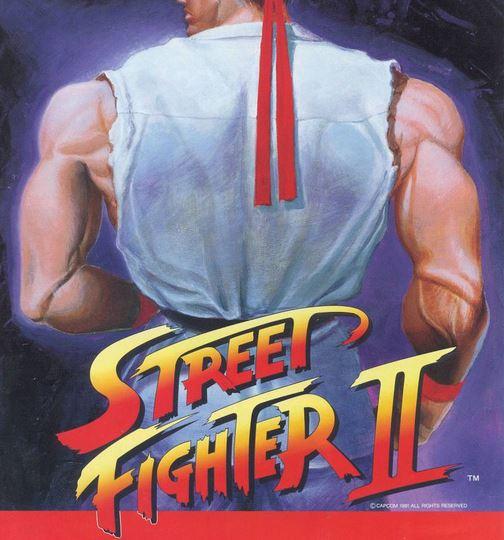

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Video game historians and connoisseurs alike often tout Capcom’s epic fighting game Street Fighter II—released in 1991—as a revolution; it's indisputably one of the game industry’s greatest successes and marks the dawn of the fighting game boom that defined the '90s. The franchise sold more than 30 million units, provided inspiration for sequels and spin-offs, and remains a major—if kitschy—mainstay of the gamer community.

While the creativity of Street Fighter II is fascinating in its own right, the story behind its creation is even juicier, revealing a not-so-subtle dialogue between the United States and Japan. The game is an odd testament to the simultaneous strength of the nations' economic relations and profound cultural differences.

So here it goes: Reflecting the larger Reagan-era significance of the two economies, Capcom’s two key offices in the 1980s were in Japan (which primarily worked on the game’s creation) and the U.S., which primarily did marketing and distribution. The Japanese team devised to crack the arcade business model of the day: They created larger, higher-quality machines for a better user experience, and focused the game on competition between players, rather than player vs. machine.

But to many, Street Fighter II's art and character development were its defining features—20 artists divided the aesthetic development of the eight characters’ designs and backgrounds. Each character was even given a unique theme song (written by composers!) to reflect his/her country of origin and (super-stereotyped) cultural background. However, the heavy-handedness of the characters—the sumo wrestler from Japan, the fire-breathing yogi from India, a beast-man from the jungles of Brazil—made some on the U.S. team uneasy. Whether this trepidation was in fact racial sensitivity, growing up in a comparatively heterogeneous country or something different altogether is hard to say . . .

Another area of contention: The U.S. marketing department decided to follow the industry practice of Americanizing the Japanese art style for a U.S. audience, overriding the stringent objections of the Japanese team, as well as some from the U.S. There were also major differences in corporate culture in the two Capcom offices, as one U.S. marketing member said:

"I had a nice, big office in Santa Clara and I got paid a ton and all my sales guys drove Porches and Mercedes . . . we golfed Pebble Beach every month. It was crazy. I go over to Japan, and my same counterpart is making a fraction of what I'm making and he's sitting in a cubicle."

Said counterpart probably drove a sensible, Japanese-made car too. In the end, the friction and synergy of the combined Japanese and American team created a product with record-setting, mass appeal.

Now, if only we could collaborate on the mass production of sushi hamburgers . . .