Tonight marks a rare event: the debut of a TV show about an ass-kicking comic book character who's also (wait for it) a woman. With a vagina!

Marvel's Agent Carter will tell the story of Peggy Carter, a Strategic Scientific Reserve Officer in the 1940s who, according to the show's executive producer, has the superpower of being continuously underestimated by those around her. (We'll leave the palpable irony of a woman's power being her percieved weakness for another day.)

Early reviews are praising the show's "super heroine" and "feminist message" couched "in superhero fun." Played by Hayley Atwell, Agent Carter is poised to shift Hollywood's white-male, Franco+Rogen-steeped paradigm, reminding the entertainment world that women are not only worthwhile subjects—imagine that!—but they can also draw a devoted crowd and the sweet sound of cascading cash.

“It’s absolutely vital that we’re saying to Hollywood—and to the world—female-ce

ntered roles are important. They are watched. They are bankable. The audiences want them.” — Hayley Atwell tells Entertainment Weekly.

Agent Carter also marks Marvel's first-ever, female-run project, helmed by longtime writing partners Tara Butters and Michele Fazekas; basically we're looking at a deluge of damsels decidedly not in distress.

But amid all this fist-pumping and vagina swagger is a rich history of homage; debts and gratitude must be paid.

It's no secret that the comic book world is chock full of crime-fighting manly men heroes: Iron-Man, Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Captain America, Wolverine, Professor X, Magneto, The Hulk, The Green Lantern . . . need we go on? Amid the morass of testesterone, a program taking the time to tell a woman's story feels, sadly, like a true revelation. And it's one that owes a lot to the woman who arguably opened the door for all female heroes to come: Wonder Woman.

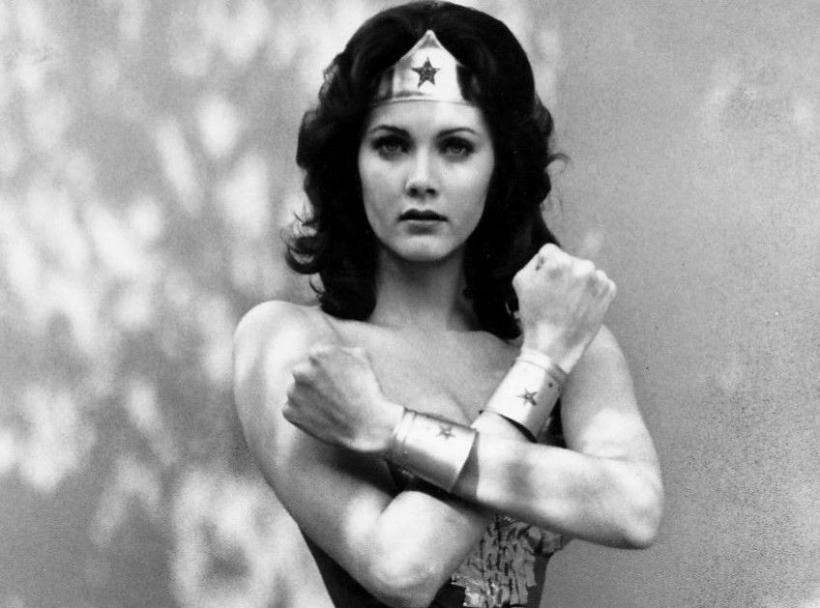

True, in many ways, Agent Carter and Wonder Woman are worlds apart—Carter is a Marvel hero with no mystical powers, while Wonder Woman is a DC creation with indestructible bracelets, a magical lasso, and an invisible airplane at her disposal. But it was one that, in many ways, begat the other. Wonder Woman proved to the world—during an era fraught and seemingly forged with and by sexism—that ladies could play (and properly punish with panache!) in the comic book world too.

Today, Wonder Woman continues to dominate headlines; at last year's Comic-Con, one of the most buzzed-about announcements was the reval that she would play a key role in the upcoming Batman vs. Superman film, in an undeniably grittier iteration.

As The Guardian has put it, "Wonder Woman isn't just a feminist icon—she's the feminist icon." Here's why that statement is far from hyperbolic—and why any mention of Agent Carter and her ilk owes a serious debt to the lasso-wielding woman who launched a movement.

1941: Wonder Woman Created by Harvard-Educated Proto-Feminist

Wonder Woman wasn't the first female superhero—Black Widow and Bulletgirl beat her to the game—but she was the first molded from a distinctly proto-feminist perspective. The character was originated by Harvard-educated psychologist and lawyer William Moulton Marston, whose vision for the character was at once progressive and gender-reductive. As Marston saw it, female leadership represented the future, since women could counterbalance stereotypically male urges for violence and war. "Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world," he wrote in a letter to comics historian Coulton Waugh.

In an interview with Family Circle in 1942, Marston further expressed his desire for a new kind of female icon:

"I tell you, my inquiring friend, there's great hope for this world. Women will win! When women rule, there won't be any more [war] because the girls won't want to waste time killing men—I regard that as the greatest no, even more—as the only hope for permanent peace."

This conception was historically contextualized; at the time, women were entering the workforce in droves as men fought in WWII, prompting early stirrings of the women's rights movement.

For context, consider that it would be another 20 years-plus before one Agent Carter first appeared in comic books.

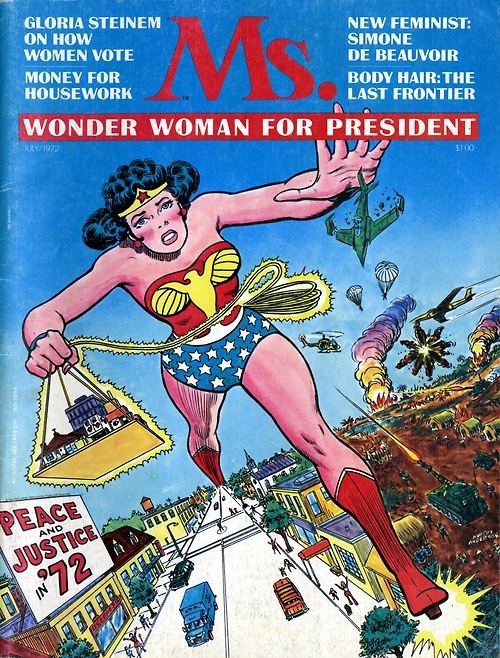

1972: Wonder Woman Graces Inaugural Cover of Ms. magazine

In the 1970s, when feminism was coming to the foreground, Gloria Steinem selected the superhero as the cover girl for the very first issue of her new magazine Ms. The depiction was not so much an overt celebration of Wonder Woman as it was a critique of what she had devolved into; after the war ended, and women re-entered the home, Wonder Woman became defined less by strength and general bad-assery, and more by domesticity and romance.

In the 1970s, when feminism was coming to the foreground, Gloria Steinem selected the superhero as the cover girl for the very first issue of her new magazine Ms. The depiction was not so much an overt celebration of Wonder Woman as it was a critique of what she had devolved into; after the war ended, and women re-entered the home, Wonder Woman became defined less by strength and general bad-assery, and more by domesticity and romance.

In total, Wonder Woman would grace the cover of Ms. three times—including, in 2012, for the magazine's 40th anniversary issue.

Late 1980s: George Perez Crafts a Staunchly Feminist Wonder Woman

In the '80s, comics book legend George Perez, a self-proclaimed "staunch feminist," took over writing Wonder Woman comics, crafting storylines with the help of Steinem herself. His goal? Enable the character to live up to her status as “the sacred icon of feminism." Alas, his tenure overseeing Wonder Woman would last a brief five years.

1990s-Present: Wonder Woman Becomes Hypersexualized Balloon-Boobed Bimbo

After Perez stopped writing Wonder Woman, the character fell victim to a larger movement in comic books to craft female characters as hypersexualized conduits for male geek desire. As female comic book writer Trina Robbins has stated, Wonder Woman became one of many female heroes with "balloon breasts and waists so small that if they were real humans they’d break in half.” This conception of Wonder Woman has more or less endured into the 21st century, crudely shifting Wonder Woman from an icon of feminism into an icon of male sexual fantasies.

Despite this rather tragic devolution, it's worth celebrating all Wonder Woman was, and all that she remains as an emblem and blueprint for a new kind of hero. We'll be watching Agent Carter eargerly, hoping that amid her pincurls and pinstripes and her palpable struggle against the patriarchy, we can keep that flickering flame of feminist hope—first provided in the pages of a comic book more than 70 years ago—alive.

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)